When the Japanese were planning their attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, they knew we would launch a counteroffensive. Their plan was to force us to attack strong points supported by interlocking air cover across the South Pacific, and through this process wear out our Navy and what the Japanese considered the weak political will of the American people to carry on the war. This final World War II post covers our counterattack, beginning after the Japanese retreat from Guadalcanal until the surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri battleship on September 2nd, 1945. But before diving into the history of naval actions, kamikaze suicide bombers, and the Marines' close quarters fights against fanatical Japanese resistance through the jungles and underground cave systems across the Pacific, I am going to start with the story of broken codes, an ethical dilemma, and, ultimately, of an assassination.

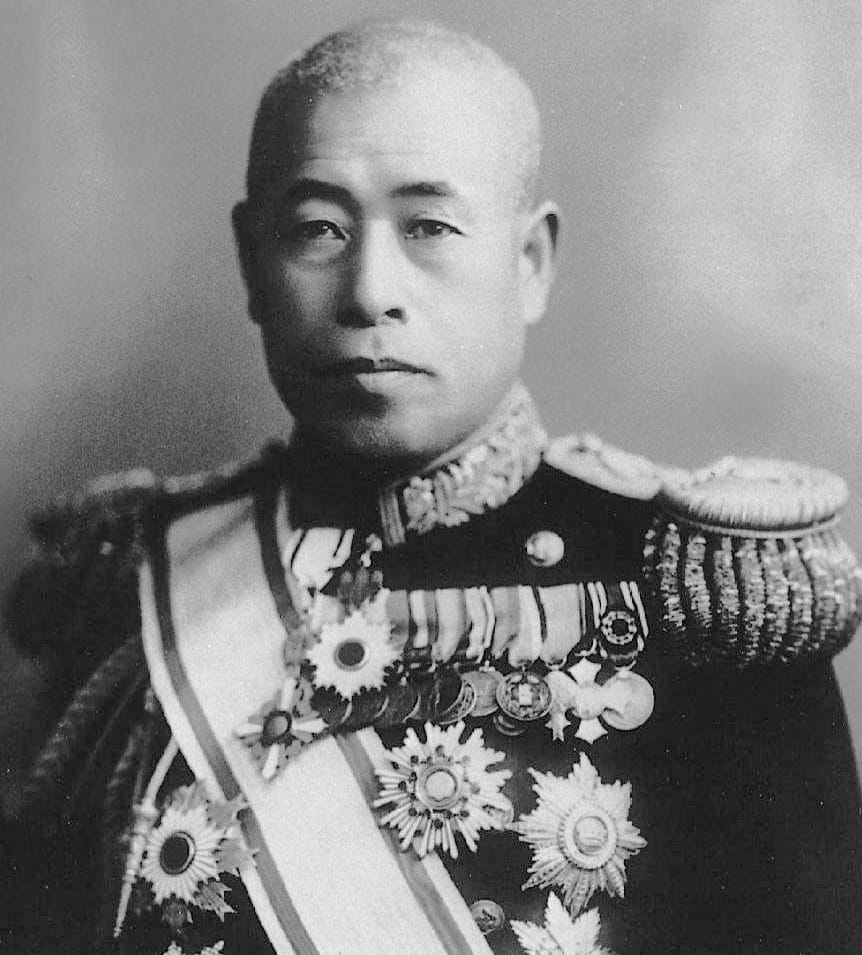

Killing Yamamoto

Our story begins in a basement in Pearl Harbor on April 14th, 1943, with a coded message. Conveniently enough, we had thoroughly broken the Japanese naval codes by this point and so only a few minutes after intercepting this code, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Alva B. "Red" Lasswell read the decrypted message, jumped out of his chair and yelled, “We’ve hit the jackpot!” because he now held in his hands the exact travel itinerary of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor sixteen months ago, and the commander in chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The full message revealed that Yamamoto would fly escorted by six Zero fighters from Rabaul to arrive at Balalae at 0800 on April 18th.

The decrypted message was quickly brought to the commander-in-chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz. Nimitz read the decrypted message, looked up, and asked to nobody in particular, “Do we try to get him?”

There were some good arguments against the attack. The only American fighters with the range to intercept Yamamoto’s flight was the Army’s P-38 Lightning, and even then, only with supplementary fuel tanks. If the Japanese deduced that the unusual appearance of Army fighters far from their normal patrol zones was not just a very lucky coincidence, they could very well realize that their operational codes were broken and change them. Even if the Allies could break the new set of Japanese codes, the information blackout until we did could cost thousands of lives and imperil ongoing operations.

There was also the moral question. Today we, the United States, conduct targeted killings on an almost daily basis via drone strike and other methods, but almost eighty years ago the speed of communication and war was just getting fast enough to allow these sort operations to take place. Of course, men on both sides were getting shot, drowned, burned to death, and blown to bits every day, but whether United States wanted to get into the business of targeting specific individuals was still an open question at that point. How important was killing Yamamoto?

Nimitz weighed the risks and morals of the decision and decided that killing Yamamoto was a legitimate military operation and that the benefits outweighed the risks. After the war, a story emerged that Nimitz radioed Washington about the choice and President Franklin D. Roosevelt made the midnight decision to kill Yamamoto, but if so, there is no record of it. Sure, the records could have been destroyed, but we have records from many more controversial decisions which were not destroyed. I personally think that Nimitz weighed the factors and made the decision himself to kill Yamamoto, reflecting the sentiment of one of the cryptologists in the basement where the original message was decrypted to, “get that S.O.B.”

Late in the night of April 17th a squadron of eighteen of Army P-38 pilots took off from Guadalcanal with precise coordinates and orders to shoot down anything that flew once they arrived at their destination in the morning. And Yamamoto was right on time. The eighteen P-38 pilots dropped their external fuel tanks and broke into two groups. All but four of the P-38’s flew up high to run interference on any Japanese fighters while the other four beelined toward the two escorted light-bombers, one of which carried Yamamoto. The two bombers immediately split: one dashed inland over the island of Bougainville and the other sprinted out to sea. Pursuing the bomber fleeing inland, LT Rex T. Barber lined up the bomber in his gunsights while his wing man fended off Japanese escorting Zeroes and fired into its tail section. Decades later, Barber described watching as his bullets ripped into the bomber and “its rudder and a good portion of its vertical fin came off.” The mortally wounded Japanese plane spun and crashed into a fireball of red among the green of the mountainous jungle.

LT Barber then turned and sped after the other bomber which had fled out to sea, flying so low that’s its props made waves and spit up sea spray in its wake. Again, it was LT Barber who got the killing shot as the rest of the P-38’s fended off the escorting Zeroes, opening up with his .50 caliber machine guns and 20 mm cannon. At close enough range where he could see and hear the shells ripping apart the bomber’s fuselage, the low-flying plane refused to go down. “Blow up dammit!” he screamed. “What do I have to do?” Finally, as he described it, “a huge puff of smoke, followed by an orange flame, burst from the right engine cowling,” and the second Japanese bomber disintegrated into the sea.

Yamamoto was now, definitively, dead. We made a point of announcing that our Australian allies reported the group of Japanese planes which turned out to be a believable enough cover story that the Japanese did not change their codes. It was a total victory. The death of a national hero was a huge morale shock in Japan and coming exactly one year and a day after the Battle of Midway, there could be no doubt that the strategic initiative was not fully in American hands.

Admiral Yamamoto's plane crash sight in what is today Papua New Guinea.

Arsenal of Democracy

By the middle of 1943, the American fleet was reaping the full rewards of Roosevelt’s Two Oceans Act building boom which had been redoubled immediately after the attack at Pearl Harbor. The first of what would be twenty-four Essex-class fleet carriers was being commissioned and armed with Hellcat and Corsair fighters, and Helldiver and Avenger-class bombers. While Japan’s marquee fighter, the nimble Zero, was the best in the Pacific back in 1941, the new American plane classes, well, outclassed their Japanese counterparts in literally every way.

To put these numbers in context, Japan possessed six fleet carriers when they attacked us at Pearl Harbor, had promptly lost four in the Battle of Midway, and would only build five fleet sized carriers throughout the rest of the war, two of which were completed so late in the war and bombed in port that they never saw action against an American ship. The ratio was at least as lopsided when you compare the more than 1,000 battleships, escort carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, submarines and amphibious ships the Navy would produce over the course of the war. In fact, to give you an idea of the literally unparalleled naval building boom occurring, the Navy ended the war with 6,768 commissioned ships in service when you include the 2,700 amphibious craft, which of course does not include the hundreds sunk by enemy fire, weather, mishap and all the other eccentricities of wartime.

Against this impending tidal wave of steel coming their way, the Japanese were badly overextended. In the Pacific, the Japanese had the same vulnerability as an island power that the British faced, and the United States submarine force over time would take advantage of the Japanese homeland’s need to ship resources from across their far-flung empire to the homeland, and then ship weapons, food, fuel and every other conceivable good back out to China and the hundreds of outposts spread across tens of millions of square miles of Pacific Ocean. Japan simply did not have the merchant marine to support the demand, and because of their frantic need to produce capital ships to take on the American fleet for control of the sea, they were forced to underinvest in the escort ships to guard the merchant marine they did have. This combination meant that the submarine war absolutely slaughtered Japanese shipping.

We produced so many ships during WWII, that after the war there was really not other option other than putting all of it in long term inactive storage... aka the Mothball Fleet.

The War Below

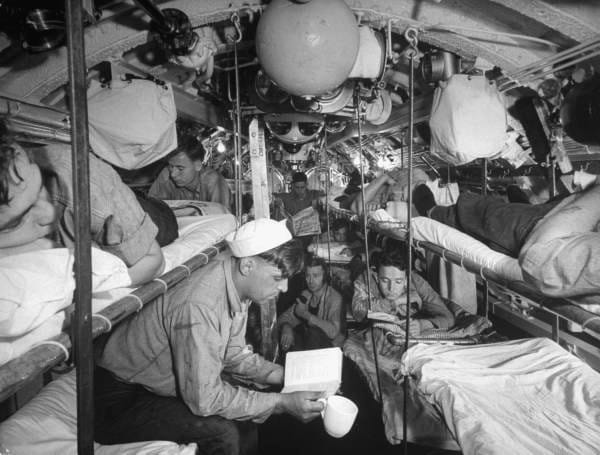

When we entered the war, the United States possessed seventy-three submarines and Roosevelt immediately unleashed them against all Japanese targets, prewar conventions and treaties be damned. The problem was that these submarines were short on torpedoes, and like early German torpedoes, our torpedoes did not work very well. They variously ran too deep, turned back on the submarine which launched them, or hit a Japanese ship only to lodge into the side without exploding. Worse, while Japanese ships were returning to port with unexploded American torpedoes in their sides, the Navy Bureau of Ordnance refused to believe their torpedoes were faulty and blamed poor shooting. Still another early factor stacked essentially in favor of Japanese trade was official naval submarine policy! It directed submarines to preferentially target heavy warships which had the unfortunate habit of fighting back, instead of targeting defenseless merchants and tankers which the Japanese simply did not have enough light ships to convoy safely. After the first year of war in the Pacific, this began to change, and the Japanese toll was high. Unlike the German system, American submarines early in the war were lone wolves, assigned a geographic area where they hunted for any of the individual Japanese merchantmen unlucky enough to be spotted in their quadrant, although this changed as more submarines came online in 1944 and ’45.

Aboard the old, World War II-era submarines, life was… not great. The boats were small, men shared racks in a delightful process called hot-racking because the tiny rack you split with another sailor was still hot from his body heat when you swapped spots so you could sleep. There was no bath or shower, just a bucket and sponge, sailors ate in whatever corner they could find, and the air during long dives became fetid with cigarette smoke, body odor and fumes.

The two-month long patrols these boats went on were trying, but for all of 1942, they achieved very little success. That changed in early 1943 when Charles Lockwood became the new Commander of Submarines in the South Pacific. He took the reports of faulty torpedoes seriously and forced the Washington D.C. corps of the navy to design a better torpedo, ushered in a new and improved class of long-range submarine, and unleashed the full might of the exponentially expanding submarine force against the practically defenseless Japanese merchant fleet. Wartime predation by our submarines got so bad that the Japanese ran out of ships. Their oil tankers could not get through from what is today Indonesia, and so they resorted fueling their ships with soybean oil, which starved the population of Japan and the unfortunate countries under Japanese occupation. Essentially, our subs successfully did to the resource-poor island nation of Japan what German U-boats tried (and failed) to do to the resource-poor island nation of Great Britain by starving it of the resources needed to fight a modern war.

By 1944, our submarines were the best in the world. They were larger and stronger than any before the start of the war and carried both surface and air search radars, night periscopes, and new acoustic homing torpedoes. The crowning jewel achievement of the submarine forces was the sinking of the Japanese super-carrier Shinano. The Shinano started construction as the third in a class of super-battleships and converted partway through her construction into an armored carrier displacing 71,890 tons when fully loaded, making it the largest carrier ever built until 1961 when the U.S. Navy commissioned the nuclear-powered USS Enterprise. The Shinano was in a vulnerable position since she was just shifting ports within Japan to evade U.S. bombing and not fully sea-worthy when she was spotted by the USS Archerfish. The Archerfish fired a six-torpedo spread. Four torpedoes hit just above the blister armor belt and opened the Shinano up to the sea. Ten days after her commissioning and after only sixteen hours at sea, the largest, most expensive carrier of the war was sunk.

The South Pacific Campaign

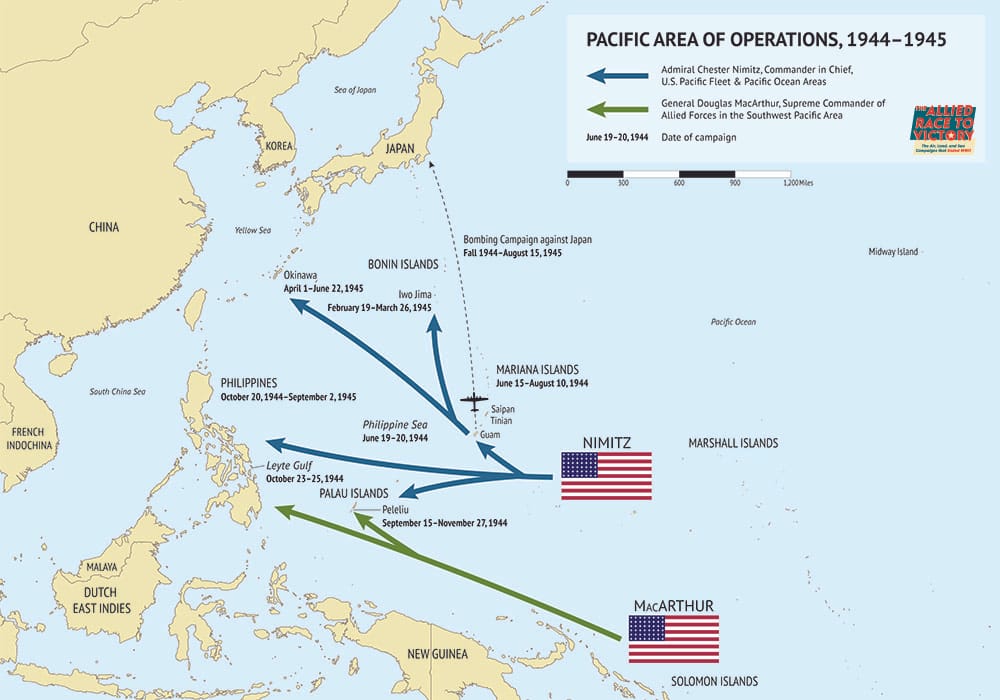

Elsewhere, in 1943, the advance in the Southern Pacific continued unabated. The main complicating factor was the fact that, unlike the Northern Pacific campaign which was hopping from island to island in a beeline for mainland Japan, MacArthur had essentially committed the United States to a parallel southern strategy of advance through his promise of “I will return” when he evacuated from the Philippines. There is a lot to say about McArthur on personal level. He was undoubtably a genius, a hero a dozen times over in World War I, a public darling, and at the same time was aptly described in Admiral William "Bull" Halsey’s 1943 letter to Admiral Nimitz as “a self-advertising Son of a Bitch.” I’m going to save a deeper dive into him for the next episode which will cover his role in the years following World War II and the Korean War. But for now, it is enough to know that MacArthur exercised strategic control over all military operations in the Southwest Pacific, Halsey had to work under him, and despite a few rocky patches between the two giants of the war, operations proceeded pretty darn well. The duo achieved overall success in the theater against what the Japanese termed their “New Operational Policy” of defending individual strong points to the literal last man. This approach resulted from the belief that Yamato-damashii, which roughly translates into Japanese spirit and represented what the generals in charge of the government believed was the “brave, daring, and indomitable spirit of the Japanese people” would eventually triumph over American wealth and numbers. If nothing else, it would hopefully wear out the American will to fight and enable a negotiated peace which would leave Japan with something.

War on the Beaches

“To catalogue these campaigns fully and faithfully,” to steal a paragraph from legendary naval historian Craig Symonds’ book WWII at Sea, which is well worth reading, “would require a detailed account of every Allied landing, every Japanese counterattack, every night surface action, and every bitterly contested yard of jungle, and even then, it would fail to do justice to either the events or the participants. Many of the operations, however—and especially the naval battles—followed a common pattern. First, because the Americans could select their targets from a score or more of possible invasion sites, they often faced relatively modest initial opposition on the beach. Soon enough, however, and often within hours, the Japanese reacted: first with air assaults, then with a naval surface force, and finally with overland attacks through the jungle. The moment the Allies stepped ashore, they knew that a Japanese counterpunch was only a matter of time, and usually not very much time. Since the moment of greatest danger to the invaders was when the big landing ships were unloading, a lot depended on how quickly the transport and amphibious ships could get in, unload, and get out.”

After a few iterations, by which I mean bloody island slogs where hundreds of men died and blood seeped into the sand and jungle across the remote Solomon Island chain, we had the unloading process down. What had taken five days at Guadalcanal now took one, but the Navy and Marine Corps still had to deal with Japanese strafing runs and bombers launched from nearby islands over the beaches, and with Japanese surface units in the middle of the black night. In these middle-of-the-night actions Japan’s world-leading, long-range Long Lance torpedoes fueled by compressed oxygen squared off against far-superior American radar technology which gave us a huge night gunfire advantage, more than reversing the previous Japanese pre-war training advantage in night fighting.

It took 32,000 Army soldiers and 2,000 Marines to capture the first island of Munda against 5,000 Japanese defenders at the cost of 1,200 KIA and twice as many wounded. Following this slugfest and looking at the prospect of fighting the twice as numerous Japanese dug in on the island of Kolombangara, MacArthur and the Navy pushed through what is known today as the “island hopping” strategy. This strategy called for bypassing the most strongly held Japanese positions whenever possible. MacArthur instead chose to attack the island of Vella Lavella , which was defended by a mere 250 Japanese soldiers. This strategy to leave large garrisons of Japanese behind the “front line” as it were, was descended from versions of War Plan Orange if you remember back to the Interwar episode, saved tens and tens of thousands of lives on both sides and was one of the most important strategic decisions of the Pacific War. This decision to leave heavily armed unsinkable aircraft carriers, aka islands, in the rear was only possible because of the naval superiority we were wresting away from the Japanese. Had the Japanese been able to supply and transport troops between the islands and then attack our islands in our rear, this strategy would have been impossible. Bypassed Japanese garrisons were either evacuated or left to simply wither on the vine. Isolated Japanese garrisons resorted to farming and fishing, and for the most part surrendered after World War II, although, there were a few holdouts who surrendered or were killed throughout the late 1940s, the 50s, 60s, and finally, the last two who formally surrendered in 1974, twenty-nine years after the war officially ended.

The Central Pacific Drive

The Southern Campaign was not moving fast enough for Admiral Ernest King’s liking. Instead of the relatively small leaps of island-hopping MacArthur was conducting, King envisioned leaps of hundreds of miles at a time across the Pacific. The Central route would allow the navy to come into direct conflict with the remaining main Japanese battle fleet, the environment was better, and ultimately the Central Pacific was a more direct route to the Japanese homeland. As soon as we seized a few islands near the homeland, construction could begin on massive air bases from which to bomb the war machine into cinders at its source. MacArthur, who was ever conscious of any slight and the impact on his public image, was not happy with this. He suspected President Roosevelt of trying to sabotage the South Pacific campaign out of the fear that a victorious (and known Republican) MacArthur would wage the upcoming 1944 presidential campaign against him. This accusation was not true, and I think that it was pretty clear that we would have and should have focused on the Central Pacific route from the beginning had MacArthur and his star power did not force the southern strategy, but hey, that’s just me.

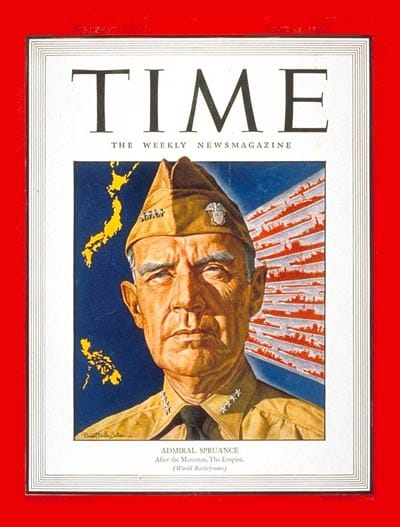

With the addition of the massive new Essex-class carriers rolling out of the dockyards every month, the Navy now had a veritable abundance of portable air power, and down the center we went. Twelve battleships, nine fleet carriers, eleven smaller carriers, twelve cruisers, and enough amphibious ships to crush island after island descended on the Japanese under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance, the namesake of my first ship in the navy, good ‘ol DDG-111.

The first target was Tarawa, part of the Gilbert Island chain. It was a tiny, tiny 1 square-mile atoll whose highest elevation is ten feet and most of the surface area was taken up by a Japanese airfield they used to command thousands of square miles of sea lanes around the atoll. Despite its size, Tarawa was defended by 5,000 well-supplied, and superbly fortified Japanese troops. The garrison’s commander told his men “A million men cannot take Tarawa in a hundred years.” Well, read on and find out if he was right…

Hell at High Tide

On the American side General Holland M. Smith, who led the assault, promised his men that the fortress atoll would be softened up with “the greatest concentration of aerial bombardment and naval gunfire in the history of warfare.” This began with the battleship Maryland’s eight sixteen-inch main batteries at 0500. The rest of the massive invasion fleet followed suit. Hundreds of planes dropped a rain of bombs on the island. “Surely no mortal men could live through such a destroying power,” a journalist from Time Magazine wrote. The island shook with the fury of 3,000 tons of explosives and when the dust settled there was not a stick on the island standing. The landing craft moved in at 0830 and the Japanese guns were silent, presumably blown away by this greatest concentration of firepower in human history up to this point. And then, when the landing craft were half a mile away, the Japanese guns opened up all at once.