Yesterday, December 7, 1941 a date which will live in infamy the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that Nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its Government and its Emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific. Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American Island of Oahu, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack.

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time the Japanese Government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu.

Yesterday the Japanese Government also launched an attack against Malaya. Last night Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong: Last night Japanese forces attacked Guam. Last night Japanese forces attacked the Philippine Islands. Last night the Japanese attacked Wake Island. And this morning the Japanese attacked Midway Island.

Japan has, therefore, undertaken a surprise offensive extending throughout the Pacific area. The facts of yesterday and today speak for themselves. The people of the United States have already formed their opinions and well understand the implications to the very life and safety of our Nation.

As Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense. But always will our whole Nation remember the character of the onslaught against us.

No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.

I believe that I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us.

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger.

With confidence in our armed forces with the unbounding determination of our people we will gain the inevitable triumph so help us God.

I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.

-President Roosevelt's Address to the Congress Asking That a State of War Be Declared Between the United States and Japan, December 8, 1941 (less than 24 hours after the attack on Pear Harbor)

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was a monumental gamble and the single most fateful decision of World War II. But the decision to strike at the heart of America’s Pacific fleet was not a decision the Japanese took lightly.

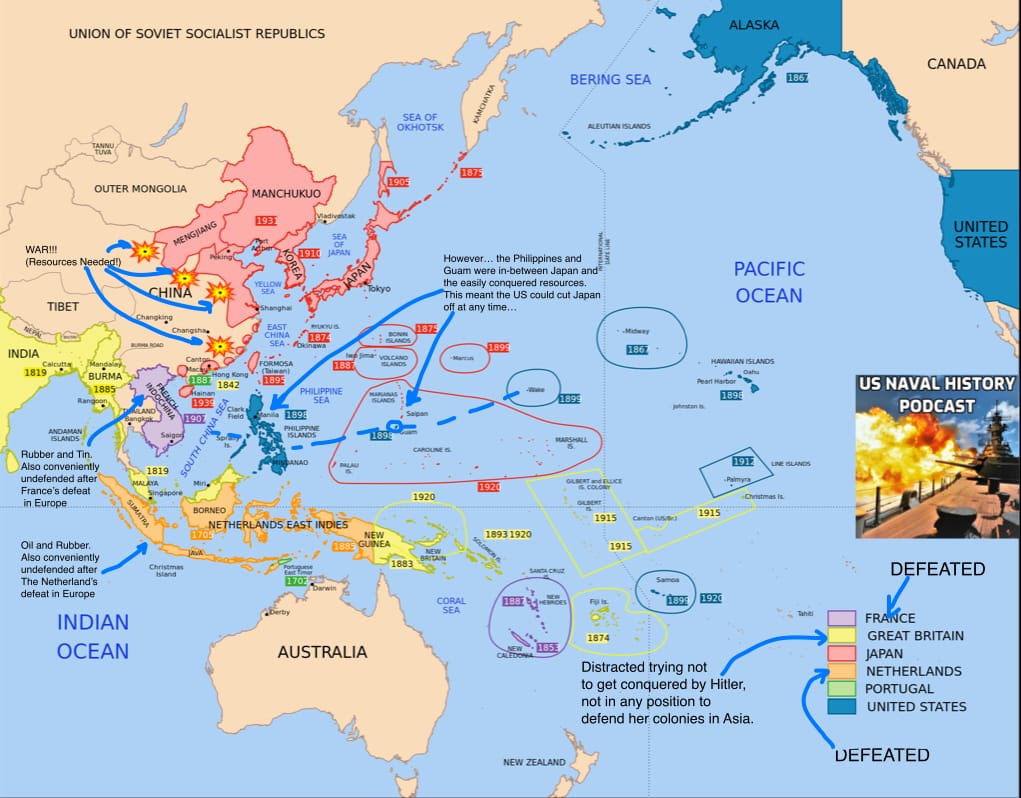

In the years leading up to WWII, Hitler was not the only one looking east for land and resources. From halfway around the world, the Japanese fixed an uneasy and calculating eye across the broad Pacific towards the United States. The driving economic issue was that the island of Japan lacked most of the raw materials essential to sustain a modern industrial economy, including iron, copper, tin, zinc, rubber and, most importantly, oil. These could, of course, be purchased from overseas, but the problem was that this course created a dependency that was intolerable to the Japanese government, especially after we Americans began to impose sanctions and conditions on further sales. At the time the United States was the world’s biggest oil producer and American oil sanctions meant that Japan had a choice, find another source of oil or bow to American demands they withdraw from their war in China. By the 1930s, many Japanese had come to believe that they must choose between accepting Western interference as a price of continued economic growth and foreign policy independence, or forcefully establish economic independence by taking those commodities for themselves.

The cultural component of Japanese policy was more nuanced. Japan’s unprecedented economic transformation from an isolated feudal hermit-kingdom into an industrial-era great power inside the space of a single lifetime created profound societal challenges. The population remained overwhelmingly isolated from the rest of the world and by the 1930s society was militarized to a degree which is pretty much unmatched by any country in the world today. In their transition to a great power, Japan wholeheartedly adopted a British-style navy, complete with copy-cat uniforms, ranks, protocols, and technology. The wholesale adoption paid off with British-style dominance at sea in successive total victories against the Chinese and Russian fleets less than 50 years after opening itself up to the modern world.

Yet, the post-WWI Washington Naval Treaty had consigned Japan to a second-class naval status. The terms of the treaty were unpopular with the Japanese public and new corps of young, fiercely nationalistic junior officers. The officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy split into two opposing factions, the Fleet Faction and the Treaty Faction. The Treaty Faction argued that Japan’s already overextended finances could not afford an arms race with the western superpowers of Britain and America, and they hoped to restore the Anglo-Japanese Alliance to counterbalance rising American power across the Pacific. In the 1920s the Treaty Faction was supported by the civilian government and was predominant. However, the equally restrictive London Naval Treaty of 1930 turned many officers towards the Fleet Faction and its push for military and economic expansion into the South Pacific. As Japanese society and the government militarized in the 1930s, the Fleet Faction gradually gained the upper hand and many of the previous young, aggressive officers began to take their spots among the leadership of the fleet. The ascendancy of the Fleet Faction was complete when on December 29th, 1934, the Japanese government gave formal notice that it intended to terminate its participation in the Washington and London Naval Treaties. And with that, Japan began to build a fleet which, they hoped, could conquer the Pacific.

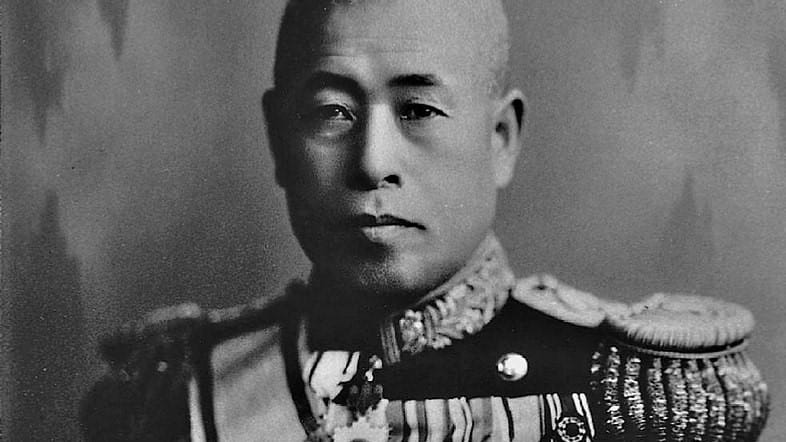

Admiral Yamamoto - the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack who opposed his own plan

One of the few Treaty Faction Admirals to survive the purges of the ascendant Fleet faction was the brilliant Rear Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Yamamoto was a calculating gambler, a visionary, and a fierce realist who had gained profound firsthand appreciation for American industrial strength from his years living in the United States. By contrast, Fleet Faction admirals dismiss America’s material and economic superiority and engaged in almost magical thinking about how the Japanese warrior spirit would and could overcome industrial might. Yamamoto found this holdover of samurai ideology naïve. Yamamoto also defied the Fleet Faction’s orthodoxy on the supremacy of the battleships. Over the course of his career, he commanded several aircraft carriers and became convinced that carriers would revolutionize naval warfare and render battleships as expensive, obsolete relics of a bygone era.

By 1937, Japan was engaged in a full-scale land war against the Chinese Empire, but the Navy kept its gaze fixed to the east. The Japanese military high command made war plans- much like our War Plan Orange, for a variety of enemies, with the United States as the most likely and the most dangerous. If the United States did intervene in China, leading to a full-fledged war, the Japanese planned to use airplanes and submarines operating from their island bases in the Pacific to weaken the American fleet as it advanced west to a final Mahanian showdown against the Japanese main battle fleet. To ensure victory in this final showdown, the Japanese built, in secret, a pair of ultimate battleships, one that would dwarf the Bismarck and come in at twice the size of its British and American counterparts. Wielding 18-inch main guns which could sink any enemy battleship beyond the range of return fire, the Yamato and Musashi were the pinnacle of battleships design, just as the era of the battleship was closing.

By 1940, events in Europe had created an enticing opportunity for Japan. The Army’s war in China was bogged down but the German conquest of France and the Netherlands had left the vast and resource-rich colonial holdings of each country ripe for the taking. If only these colonies could be taken, the Japanese military dictatorship reasoned, Japan would have the resources to finish off the Chinese and assert Japan’s true place in the sun. The only problem was that plan was the United States. You see, in between these rich and defenseless colonies and mainland Japan was the United States’ Philippine colonies. Even if the United States did not declare war in response to Japan’s latest aggression, America would still be in a position to control the fate of Japan, which was unacceptable. Since many officers saw eventual war with the United States as inevitable, the logic went that Japan might as well seize the initiative. This convoluted logic chain led to only one conclusion: war against the United States. Yamamoto was appalled by this conclusion, but there was nothing he could do. The minds that mattered were made up. “There’s nothing we can do now” he said. If “those damn fools in the army” insisted on a war against the industrially superior Americans, the only hope of victory was a quick, sharp war begun with a crippling blow. In January of 1941, Yamamoto began to work on what became plans for a raid utilizing all six of Japan’s large aircraft carriers against the center of American naval power in the Pacific, Pearl Harbor.

While Yamamoto was planning his fateful strike to the east, half a world away in Washington DC, President Franklin Roosevelt was by 1940 sitting atop a recently revived US Navy. The Japanese treaty withdraw and news from Europe had alarmed Congress enough to authorize some serious spending. The month after the Fall of France, panic swept the nation. Would Britain be next and would the United States after that have to defend the Western Hemisphere, alone, potentially against an enemy on either coast? With this potential threat in mind Congress unanimously allocated enough money to almost double the size of the fleet with the Two Ocean Act, which among its 257 authorized ships included 18 new aircraft carriers. The size of this fleet buildup showed what Yamamoto had known all along, that America had the industrial capacity to outbuild Japan many times over and a war of attrition was hopeless. But since large ships take years to build, the Japanese window of opportunity had narrowed. Their ships had been laid down earlier and if they could decisively strike after their new ships were commissioned but before the massive new American fleet came into being, maybe, just maybe, they could build the buffer they needed and sue for peace. It was a gamble, and the clock was ticking.