How do you tell the story of such a vast and terrible war in so few words? Hundreds of books and memoirs have been written on the topic and millions of deeds, heroic and cowardly, brilliant and foolhardy took place. But this is the same as in every war. Zoom in far enough and you get the fullest range of human experience in wartime. Terror and exhilaration among the far greater swaths of boredom. Love, hate, death, rebirth, revenge, absolution and everything in between is all there on display. I will try to tell you these stories in the greater context. The context of a war that shaped the world we live in today. This post will cover the European and Mediterranean wars, from Britain’s struggle for survival, to the invasions of North Africa and Italy, and culminating with the greatest amphibious operation in human history: the landings on the beaches of France on July 6th, 1944, D-Day.

War Erupts in Europe

World War II, at least in Europe, started when the revived German Army invaded Poland on September 1st, 1939, more than two full years before the United States would enter the war after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. In that autumn of 1939, almost a century ago now, the naval war in Europe began. Unlike in World War I, the German navy was small when World War II broke out and the Germans harbored no delusions about wresting sea control from the British in an epic showdown of battlefleets. Between the end of World War I and 1935 when Adolph Hitler renounced the severe naval limitations of the Versailles Treaty, the German Navy sustained and expanded its submarine-related technical expertise through Dutch shell companies, submarines built for export, and by stockpiling unassembled parts in anticipation of the day when German submarine construction would again resume. After 1935, the German navy expanded their submarine fleet, which they referred to as U-boats, to asymmetrically counter the insurmountable British conventional fleet lead. Leading the German U-boat effort was Karl Dönitz who commanded a force of fifty seven U-boats.

The first strike of Dönitz’s U-boats came in October of 1939, against the Royal Navy’s great base at Scapa Flow on the northern tip of Scotland. Cruising silently, darkly, and low to the water, past the harbor defenses under only the ghostly green glow of the northern lights into the inner harbor, a dark shape stopped only 4,000 yards from the World War I-era British battleship HMS Royal Oak. Firing a salvo of four torpedoes at point-blank range, one jammed, two somehow missed, and the fourth hit managed to hit the Royal Oak’s anchor cable without damaging the battleship or raising the British alarm. The German submarine turned around and fired again at the Royal Oak with its stern torpedo tube, and again, missed. The U-boat’s commander, undeterred still undetected, retreated away from the Royal Oak to reload before returning again an hour later to unleash another volley of three torpedoes, this time to affect. Three blasts rocked the Royal Oak. Water and pieces of the ship’s hull flew over a hundred feet in the air, followed by flames and black smoke as the giant ship listed farther and farther to starboard before sinking completely below the surface, just thirteen minutes after the first explosion with the loss of over 800-souls. Search lights snapped on and destroyers pulled up their anchors to search and give chase, but LTCDR Gunther Prien and U-47 escaped the harbor under cover of dark, and after one close call with British patrol boats equipped with an early form of sonar and depth charges, the next day made their way home to Germany as some of the first naval heroes of the war.

The rest of the German U-boat fleet had not been idle in these first weeks of the war either. The Germans were sinking merchant ships at the rate of 10 a week and had sunk one of the Royal Navy’s five aircraft carriers just two weeks into the war, but the destruction of the Royal Oak in the Royal Navy’s inner sanctum had a unique psychological impact on the Royal Navy and British public. But as auspicious a start as the sinking of a British battleship and aircraft carrier was, Dönitz believed that the true target of his submarine force had to be the massive merchant fleet which kept the British public fed and her factories supplied with raw materials. To do this, the German fleet was far under-strength and the flaws in German torpedo technology had been revealed, which despite numerous redesigns would continue to haunt the German navy throughout the war.

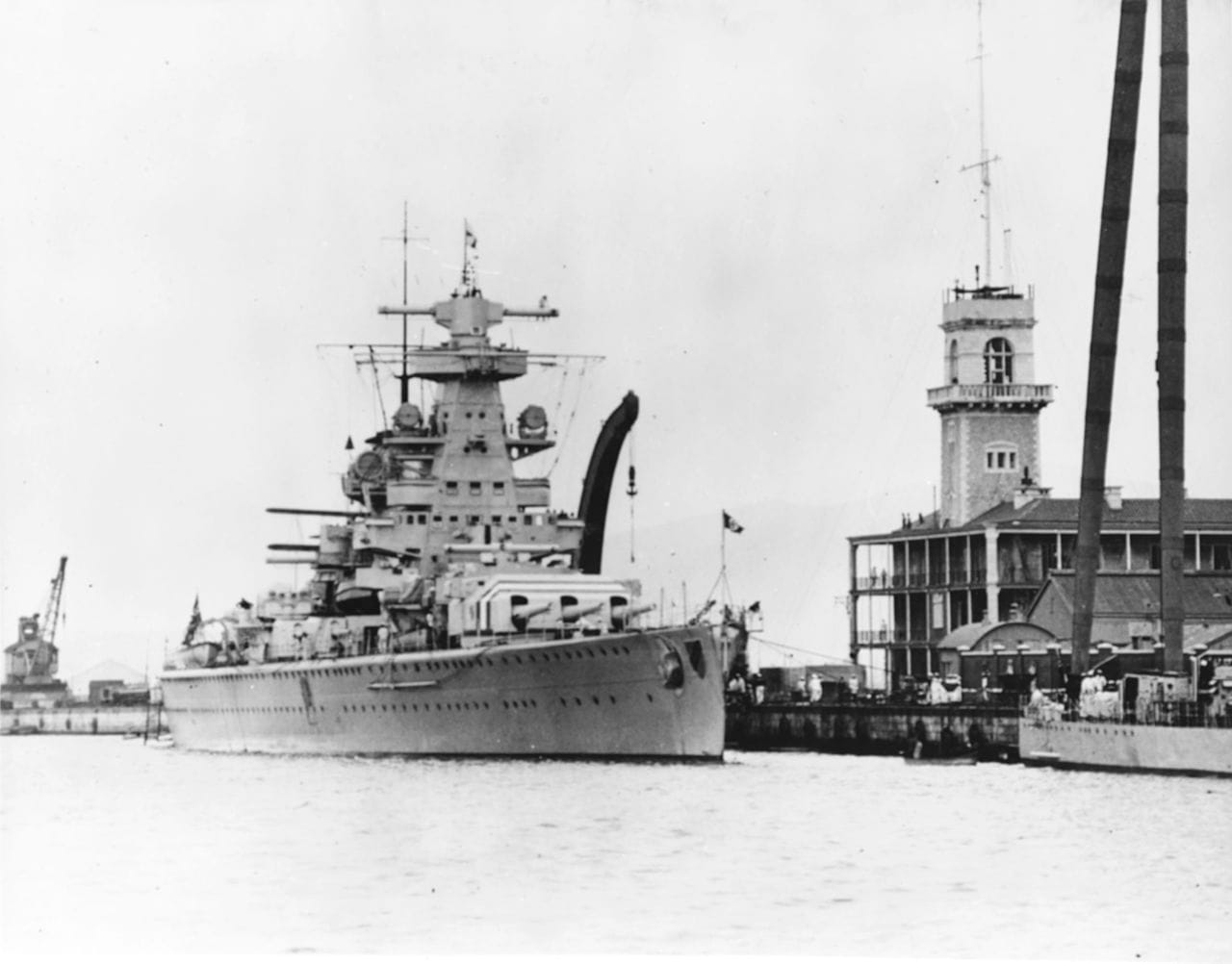

The German navy took the fight to the British merchant fleet on the surface as well. Using a pair of heavily armed and very fast cruisers known as “Panzerschiffen” or “pocket battleships,” the German surface fleet raided the Atlantic, sinking British merchantmen left and right, and using the speed of these fast ships to evade the ships sent in pursuit. If you listened to Episode Six on the Civil War and remember the raids of the CSS Alabama against Union shipping, the concept here is essentially the same. To counter this new threat, the British Admiralty created six cruiser hunter-killer groups to seek out and destroy the German pocket battleships. This, of course, filled the second half of the German objective for the pocket battleships, of forcing the British to deploy a completely disproportionate number of ships far afield in search of a few small and relatively inexpensive German assets. In the end, the most successful of the German raiders, the Graff Spee, sank nine merchant vessels between September and December 1939 before being trapped by one of the British hunter-killer groups off the coast of South America and scuttled to avoid capture by the British. The Graff Spee’s sister ship, the Admiral Scheer, would make a successful cruise in late 1940, but it quickly became pretty clear that resources would be better spent on submarines if the goal was to devastate British shipping. The relatively ineffective performance decisively tipped Hitler’s opinion towards using submarine warfare against British shipping, and the concept of surface raiders was pretty much abandoned by the Germans.

War Comes to the North

The next phase of the European war emerged on the northern front of Norway. For Germany, securing Norway was a strategic play which would allow their submarines easier, closer, and safer access to their hunting grounds around the British Isles. In addition, they could secure a supply of iron ore for the ravenous German war machine. The British were simultaneously contemplating their own offensive action against neutral Norway to deny Germany these same advantages. The Germans managed to strike first with simultaneous invasions of Denmark and Norway. The invasion of Denmark took four hours against a symbolic defense leaving the Germans poised for an all-in naval gamble against the Norwegians.

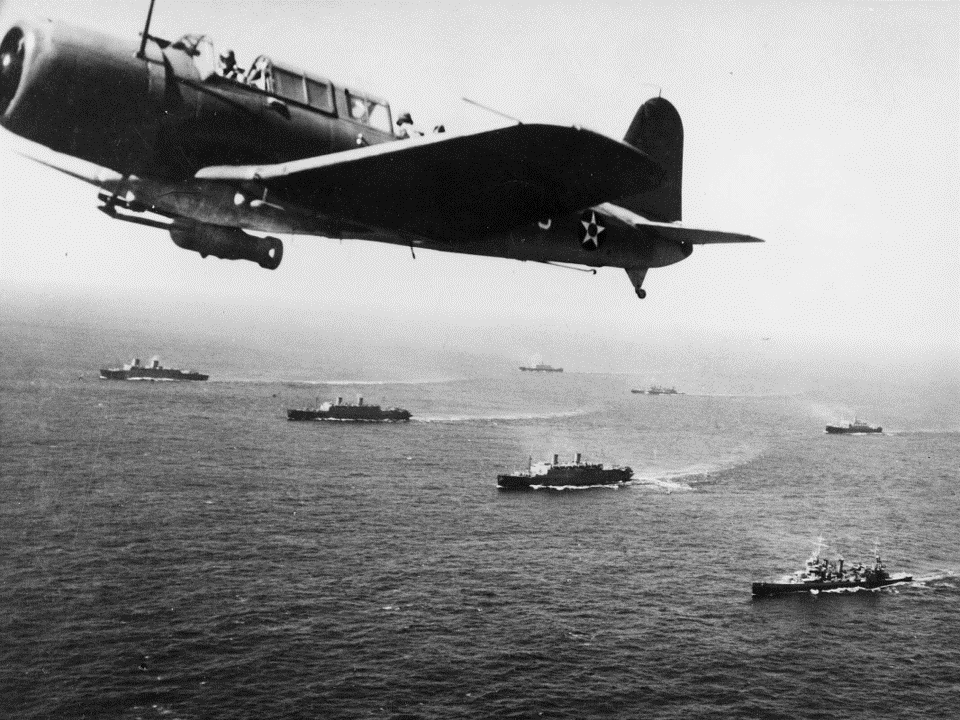

The naval planning for the invasion of Norway was complex and daring. German warships set off independently, crowded with soldiers into every passageway and deck, and arrived at key ports simultaneously. German supply ships stealthily pre-positioned themselves inside of Norwegian fjords and ports, while the German Navy’s two battlecruisers sallied forth into the Norwegian Sea as a decoy. The German invasion fleet got underway just as a British force sent to mine neutral Norway’s harbors sailed into the North Sea. Without radar, in the typically terrible visibility of the North Sea beset with snow storms and heavy fog meant that the fighting was confused and sporadic. The British and Norwegians did manage to sink or badly damage a number of German warships, but the German goal was accomplished: boots on the ground in Norway.

Compared to the intricately planned German invasion, the British counter-invasion was thrown together in a matter of days with whatever units and supplies could be loaded onto ships first. Under the continued bombing of the Luftwaffe which claimed five more warships, the Royal Navy landed British, French, and Polish exile soldiers ashore and began to encircle their German counterparts. And I say slowly because the Allied troops were advancing through waist deep snow against German air superiority. With the Norwegian campaign a mess, and fresh intelligence that the Germans were preparing for another move on the continent, and a political crisis of leadership brewing at home, British Prime Minister Nevil Chamberlain grew concerned about the overextension of the Royal Navy and made plans with his French counterpart to withdraw from Norway to save their strength for another fight.

On May 10th, 1940 the German Army proved the British intelligence good and struck again, this time in France. Less than two weeks later, the Royal Navy evacuated their soldiers from Norway to focus on the larger issue. For Germany, the gamble had paid off, but their surface navy was essentially destroyed in the process.

The Miracle at Dunkirk

In France, the news for the Allies was appalling. Just days into the German tank assault through the supposedly unpassable Ardennes Forest along the French-German border, the horribly managed French Army was on the verge of collapse. Five hundred thousand French, British and Belgian soldiers were trapped along the French coast, centered on a small, and soon to be famous port of Dunkirk. By this time, Winston Churchill had been appointed as the British Prime Minister and had one order for the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet: rescue the Army. And under the command of Vice Admiral Ramsey, the Royal Navy did just that. There is a myth in the popular imagination that the British Army was rescued by a sort of citizen navy of fishing boats and pleasure yachts, but I’m sorry to have to disabuse you of the romantic idea and report that the overwhelming majority of the evacuations were the work of transport ships and navy destroyers. Ramsey’s first order was to recall all destroyers from Norway and the shipping lanes west of the British Isles. Dozens of destroyers raced at flank speed for the English Channel. The evacuation began on May 26th, just sixteen days after the invasion of France. The German Luftwaffe had destroyed the piers and wharves of Dunkirk from the air and so the evacuation had to take place from the beach. Even the shallow-drafted destroyers could get no closer than 600 yards from the shore and so the soldiers trapped by the encircling German army had to be ferried to the destroyers one oar-powered boatload at a time, while their destroyers waited just offshore keeping a lookout for German dive bombers or fighters spraying machine gun fire into the loading or unloading boats.

There were of course thousands of men saved by small civilian craft. From Dutch canal barges, to racing yachts, to lifeguard motorboats, every available seaworthy vessel which could be commandeered was. These deputized boats were commanded by recalled Royal Navy officers and men, and sometimes by civilians who were either volunteers or were convinced to do their patriotic duty among the artillery shells and bombs by the pointy end of a bayonet. Two wooden breakwaters served as a makeshift pier and hosted a more than two-mile, six-hour long line of soldiers waiting for evacuation, which had to be terrifying, knowing that you were a ripe target for enemy aircraft.

On May 28th the Belgian army capitulated and the German armored columns again raced for the exposed British army. The British contracted their perimeter and Ramsey was given command of every destroyer the Royal Navy possessed to evacuate the bulk of the British army before it was overrun by the vastly superior Germans. It was a race against time, and if the British Army was captured, it could mean the end of the war.

While the German army raced to destroy the trapped British, the German navy also took its toll. The harrowing ordeal to get loaded on a destroyer did not guarantee safe passage to English soil. The Germans had wasted their surface fleet in the Norwegian campaign, but attacks from the air, by U-boats, and by small fast-attack craft operating under cover of night sunk or crippled twenty five of the thirty-nine British destroyers involved in the action. The losses were so horrendous that the First Sea Lord, the most senior officer in the Royal Navy, intervened to pull the destroyers out of action in order to have something in reserve to deflect the expected German invasion before he eventually was convinced by Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsey to reverse his decision.

In the end, 340,000 men were evacuated from the Dunkirk pocket, but the operation was not a victory, just a mitigation of total defeat. All of the British Army’s heavy equipment was abandoned to the Germans. In hindsight, it is easy to classify the evacuation as a miracle, but if you think back to how the world stage looked at the time it was grim. The French Army, whose fathers had so heroically held off the German horde for four years in the First World War, was falling. The British army had just retreated in abject defeat. Italy joined the war on the German side. France formally capitulated on June 22nd, and fascism looked absolutely ascendant in Europe. The naval situation was at an inflection point as well. German Admiral Dönitz’s U-boats now operated from French ports on the Atlantic, the newly allied Italian navy was formidable, and the question of the fate of the French navy, the fourth largest in the world, was in the balance.