At the dawn of the 20th century, fresh off a so-called splendid little war against Spain, the United States emerged as one of the great powers of the world, and as a colonial one with the acquisition of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and a few other overseas colonies. Leading the nation into the 20th century was Spanish-American War hero and naval advocate Theodore Roosevelt. Under Roosevelt the fleet grew, we built the Panama Canal, and the United States began to break free of our isolationist roots and exert more influence on global events. President Roosevelt’s successors, Presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson also expanded the navy and, by the time World War I kicked off, the United States was arguably the most powerful country in the world. But the Navy would not fight any significant battles during the war. Instead, as promised in the last post I am going to tell you about hands-down greatest battleship engagement in world history between the German and British main battle fleets at the Battle of Jutland, as well as about the emerging role of submarine warfare that the Germans used pretty effectively during World War I in an attempt to starve Britain into submission.

The U.S. Navy Expands

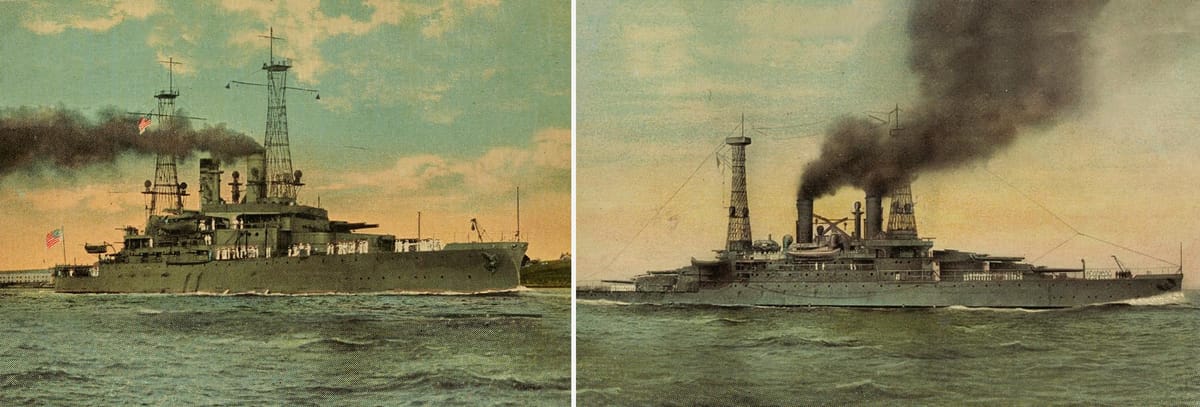

Going back to 1901, the country was riding high after absolutely crushing the Spanish and dismantling the remains of their empire in the Spanish American war and President William McKinley lead the nation with Theodore Roosevelt as his Vice President. But, less than a year into his Presidency, McKinley was assassinated, and Teddy Roosevelt became the youngest President in American history. Roosevelt was an early and fierce adherent of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theories on naval power which included the analysis that countries should build and maintain big, concentrated fleets of capital warships to defeat and drive the big, concentrated fleets of enemy capital warships from the sea in time of war. During the roughly seven years of the Roosevelt Presidency the navy would expand to 20 battleships organized into two fleets, one for the Atlantic and one for the Pacific Oceans.

During Roosevelt’s presidency, the Pacific became an increasing focus for naval planners. Just as China’s continued naval rise today makes it clear that they aspire to naval dominance in Asia, planners looking to Asia shortly after the turn of the century could see the same thing in Japan. Japan was transforming itself from isolated backwater into industrial powerhouse in a single generation. The Japanese military establishment had also read Mahan’s book, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History and invested heavily in their navy, and during this era began looking for opportunities to expand Japanese influence and territory beyond their Home Islands. In 1895, Japan had defeated China and took Taiwan and the Korean Peninsula, and in 1905 defeated the Russian Empire. The Battle of Tsushima in the Russo-Japanese War proved a lot of Mahanian points and the importance of large caliber, long range naval guns. With the ascendency of Japan and the need to protect our new colony of the Philippines, Roosevelt pushed through the Panama Canal to provide the ability to quickly link the Atlantic and Pacific fleets in case of war.

All Eyes on Panama

The thing to understand about the Panama before the era of air conditioning and other modern amenities was that it was miserable. It was incredibly hot and humid, there were mosquitos, malaria, yellow fever, swamps, mountains, rainforests and torrential rain. Various people had been proposing a canal since 1513 when Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the isthmus and thought it would make a handy shortcut and save the time of sailing around South America.

The first serious attempts at planning a canal across Central America began in the early 1800s but after the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869 a French-led consortium began seriously working on a Panama Canal. A canal across mountainous jungle proved to be much harder than digging a canal across flat Egyptian desert and between 1881 when serious work began and 1889 over 22,000 men died from disease and accidents attempting to build the canal before abandoning the project. At this time Panama was a restless province of Colombia and in 1903 the United States under Theodore Roosevelt encouraged Panamanian rebels to rebel against Columbia. When they did, Roosevelt sent 10 warships and a battalion of marines to prevent the Colombians from reinforcing their garrisons on the isthmus and essentially forced the Colombians to accept Panamanian independence. The new Panamanian government quickly agreed to turn the Panama Canal Zone over to the United States in perpetuity for $10 million. The United States spent the next decade finishing the work the French started, and it was a monumental effort. A massive set of sanitation measures reduced mosquito-borne disease while 75,000 workers toiled to build a series of dams, locks, and artificial lakes before on January 7, 1914 the Panama Canal was completed, linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Using the "Big Stick"

Elsewhere in Latin America, Roosevelt tacked the country onto an aggressive course. After the combined navies of Britain, Italy, and Germany blockaded the coast of Venezuela in 1902 when the Venezuelan President refused to pay his country’s foreign debts, Roosevelt decided that Europe was used to wielding too much influence in our backyard. Various so-called banana republic countries in Latin America were constantly going bankrupt or through revolution and providing ample excuses for European powers to interfere in the Western Hemisphere. Wielding the “big stick” of the U.S. Navy, Roosevelt declared what become known as the “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. If you don’t remember, the Monroe Doctrine was a United States government policy which held that any further attempts by European powers to take control of or colonize countries in the Western Hemisphere would be regarded as, and here I quote, a “manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” Roosevelt’s Corollary stated that the United States would intervene as a last resort to ensure that other nations in the Western Hemisphere paid their international debts and respected international property, or in plain English: ‘we’re the law around these here parts, not you’. Over the next decades, the corollary served as a justification to use military force to restore internal stability primarily when American commercial or security interests were threatened in various countries including Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti, Mexico, Honduras and the Dominican Republic. These interventions turned the Caribbean into an American Lake and were known as the “Banana Wars,” and often resulted in brutal tactics by both sides with the United States Marines usually serving as the on-the-ground muscle.

There were other theaters where the Navy was involved as well. Marines complemented the army in fighting a Filipino insurgency in the first years of the new century and a large force of warships and Marines were stationed in the China theater. After playing a part in putting down the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China, a permanent Marine contingent helped guard western enclaves in Shanghai and what is today Beijing, while Navy gunboats plied the Yangtze River protecting American lives and commerce until these forces were eventually overrun in the early days of World War II by the Japanese. If you want more details on these engagements, there are some great books on life in colonial era China and a ton has been written about American intervention and its consequences today in Latin America, but for the sake of keeping this a general overview I’m going to skip over the details of these theaters.

The Great White Fleet

Roosevelt’s crowning achievement as a navalist, though, came at the end of his second term, with the sailing of the Great White Fleet. A fleet of 16 battleships set sail from Hampton Roads, Virginia in December of 1907. Only a few people knew the fleet’s secret mission to circumnavigate the globe before it left, but soon the intent was obvious. Over the course of the next 14 months, the fleet traveled 43,000 miles, rounding the southern tip of South America and then sailing north up the coastline to Seattle before crossing the Pacific, touring Asia, across the Indian Ocean, through the Suez Canal and Mediterranean, and finally steamed home to the east coast. The voyage was a public relations triumph. Each of the dozens of port calls the fleet made showed off American naval strength and our ability to project force far from our shores, especially proving to a rising Japan that we could muster a large fleet in the event of war to defend the Philippine islands. At home, the message was just as clear. If the war against Spain did not make it obvious, this projection of force did. America had arrived and the Navy was more popular than ever, especially after the corpse of Revolutionary War hero John Paul Jones was brought from Paris to its final resting place today below the newly constructed USNA chapel amid great fanfare.

A New Era

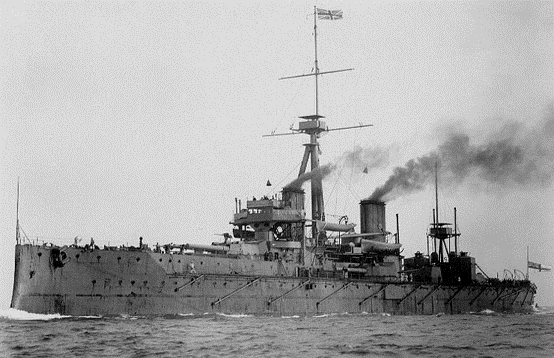

As moving and impressive as the sixteen battleships of the Great White Fleet were however, they had all been made obsolete just the previous year when the Royal Navy launched the first-of-her-kind HMS Dreadnought in 1906. To understand why Dreadnought was so revolutionary, you need to understand how pre-Dreadnought battleships were constructed. Pre-dreadnoughts would usually mount four large bore, 11–12-inch guns on two separate turrets, one forward and one aft. These main guns would be supplemented by smaller guns, in the 7–9-inch range and a secondary battery of smaller, 4–6-inch guns to fend off torpedo boats. For over a decade prior to the launch of the HMS Dreadnought naval planners knew that this setup was non-ideal. The mixed caliber main battery made fire control difficult, and each additional gun mounted also introduced a weak spot in the battleship’s armor and the extra weight reduced the speed of the ship. The HMS Dreadnought was also the first capital ship to replace reciprocating steam engines, which were unreliable and could not sustain high speeds, with turbine engines, increasing both her speed and reliability. The Dreadnought could sustain 21 knots compared with the 12 knots or so a pre-dreadnought could maintain without the risk of mechanical failure. The HMS Dreadnought wielded much heavier main guns - her eight all-big-gun armament made fire control much easier and vastly increased the range at which she could fight. The Dreadnought employed an early form of director firing and had better range-finding equipment than her predecessors, as well as a thicker and better armor scheme and improved watertight protection and compartmentalization to minimize catastrophic battle damage. All of these innovations combined allowed her to fight at long range compared to the short range of pre-dreadnought battleships. Do you remember in the last post less than a decade before the Dreadnought’s launch where Dewey took his force to within a few thousand yards of the Spanish defenders so he could use his full firepower of large and small guns? This would no longer be necessary and the speed of the Dreadnought allowed her to choose to fight at long range with accurate fire.

The idea of an all-big gun, Dreadnought-like ship was not entirely new though. An Italian ship designer brought a similar proposal to the Italian government who rejected it as too expensive. Both the Japanese and American navies had already begun building ships which incorporated elements of the Dreadnought’s design prior to the British even laying down the keel of their HMS Dreadnought. But the Dreadnought was the first all-big gun battleship with fast, reliable turbine engines, and modern fire-control and armor schemes. The combination of all of these improvements clearly split the ships and navies of the next decades into two categories, those with “pre-dreadnought” battleships and those with “dreadnoughts.” None of the technologies that went into Dreadnought were revolutionary, and very few were secret. The construction of Dreadnought was a massive media event meant to show the world the might of the Royal Navy and once it was known that the British had built a such a battleship and she worked well, it was relatively simple for anyone else with the money or industrial capacity to build or buy their own. But this was the sticking point. Every first-class navy now had to rebuild a large part of their fleet from scratch at massive expense. With this resetting of the naval standard, the Germans saw a chance to catch up to the British in terms of naval power.

This was stupid on the German part. Prior to 1890, Otto von Bismarck had steered Germany on a masterful diplomatic course of isolating France and managed to keep Britain out of the European alliance system. In the early 1900s, the British even came hat in hand, almost begging Germany to accept them as allies, which would have been a natural fit for Germany and allowed the German Empire to continue its slow consolidation of power in central Europe. But for a lot of reasons, many of which had to do with the Kaiser Wilhelm II’s obsession with national image, the Germans rejected the British which basically forced the Brits to ally with their traditional and colonial rivals, the French. Led by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the German navy intensified their warship building blitz that drove a naval arms race, which placed a huge financial strain on both great powers and further drove the British to oppose Germany in the European alliance system, which in turn ultimately was a pretty significant factor contributing to World War I's outcome. This summary is skipping over a ton of diplomatic detail and if you want more detail on the politics and alliances leading up to World War I, there is a podcast which I personally find interesting which goes into minute detail in its first few episodes called The Great War Podcast for you history geeks out there.

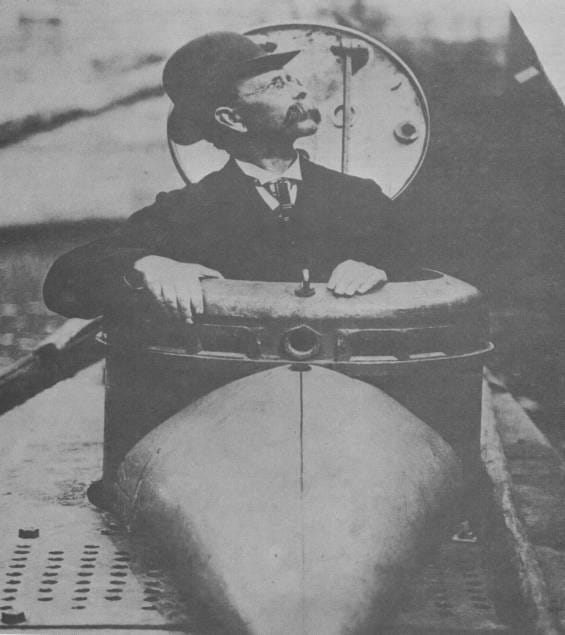

In the years leading up to World War I, the other major naval technological development was the submarine. The first modern US submarine was the USS Holland commissioned in 1900. She was a 53-foot-long experimental vessel with one torpedo tube and a pair of 8-inch guns on her deck and a 50 HP gasoline engine that was used while she was surfaced and to recharge the electric battery which was used while she was submerged. It was a bit of a technological marvel and contained innovations in ballasting, dive control, and underwater navigation. By 1910, the Navy had commissioned an additional 18 submarines making the United States by far the leading submarine power at the time. The new technology meant that the size and range of the submarines was limited, and they were designed for coastal defense, but as the technology rapidly matured the Navy kept building steadily more and more advanced submarines. In the 1910s, the Navy also began experimenting with aviation after the Wright brothers had shown that flight was possible in 1903. These early planes were primarily designed for fire control and reconnaissance, and in 1913 the Navy established its first aviation training program at the Pensacola Florida Navy Yard where naval aviators still begin their flight training to this day. In the next post, which will cover the interwar years, we will talk more about the development of naval aviation and the emergence of carriers which- spoiler alert- would render all of those fancy dreadnought and super-dreadnought battleships obsolete.

World War I Begins

All of this brings us to World War I. In 1914, Woodrow Wilson was President when the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand set off a series of events that resulted in the bloodiest period of human history up to that point. The end result of a series of miscalculations and entangling alliances in Europe was that the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire faced off against France, Great Britain, and Russia, with a few small powers thrown in on either side. After declaring neutrality at the outbreak of the war, Wilson nonetheless began to prepare for the eventuality that we would be dragged into the European fight. As the war dragged on and it became increasingly likely that the United States would get sucked into this bloody conflict, Wilson came around to the idea that the United States needed a navy second to none to claim our place and security among the great powers of the world. This “second to none” statement would represent a new philosophy, one that necessitated overtaking Britain as the premier naval power of the world. To build a navy second to none, Congress passed the 1916 “Big Navy Act” which allocated $50 million for 10 new battleships, 6 battlecruisers, 30 submarines, 50 destroyers and modernized naval infrastructure to support all of the new ships.

World War I itself was primarily a land war, with bloody trenches stretching from the Alps to the English Channel on the Western Front. The British did attempt an ambitious amphibious campaign to capture the Ottoman capital of Constantinople which failed miserably and is one of the more hotly debated topics in World War I history. I tend to think that it was probably a strategically worthwhile risk, but ultimately, the entire campaign was poorly executed, resulting in a decisive Ottoman military victory and the political downfall of the then-First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

As the war ground on, both sides were feeling the strain of years of total war. The Russian state was collapsing and devolving into civil war and the French army was mutinying, while on the Central Power’s side Austria-Hungry was faltering and the Allied blockade of Germany caused widespread shortages and suffering. Faced with a sputtering economy and deadlocked western front, the German high command reluctantly calculated that if they engaged in unrestricted submarine warfare, they could starve out the British, even knowing that this stood a good chance of bringing the Americans into the war on the British side. The Germans had already briefly employed unrestricted submarine warfare in 1915 but after the sinking of the cruise liner Lusitania, and the 128 Americans onboard, the threat of war with the United States caused the Kaiser to withdraw his submarine fleet. But now, growing desperate, the Germans gambled. If the British could be forced to surrender before the Americans arrived in force, Germany could probably negotiate a favorable peace treaty. The combination of German submarine sinkings of American merchants in the north Atlantic and the infamous Zimmerman telegram from the Germans asking Mexico about an alliance against the United States gave Wilson the excuse he needed to ask Congress to bring the United States into the war on the side of the Allies, which it did on April 2, 1917.

In Europe, the naval strategy was largely one of blockade and commerce raiding. The decisive allied naval advantage, even before the United States entered the war, allowed the Allies to blockade the Central Powers from a distance. This gave the Germans and Austro-Hungarians some room to maneuver and allowed them to conduct a few effective raids against the British and Italian coastlines, but for the most part the big battle fleets of dreadnoughts just sat in port and stared each other down. The general German strategy was to keep their High Seas Fleet concentrated and hope to use their whole fleet to engage in a decisive Mahanian battle with just a portion of the enemy’s fleet, to destroy that portion of the enemy’s fleet, and thus gain the numerical upper hand overall. The only major battle between fleets was the German attempt to catch the British by surprise in the Battle of Jutland, aka the biggest, baddest, battleship battle in world history.

The Battle of Jutland

Shortly before the Battle of Jutland, the old and conservative Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet died and was replaced by the younger and aggressive Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer. The officers and men of the fleet were happy since the past year had been spent in a monotonous routine of small excursions with no chance of meeting the British in battle. Scheer believed that his German ships, officers, and men were superior to their British counterparts and determined to prove it.

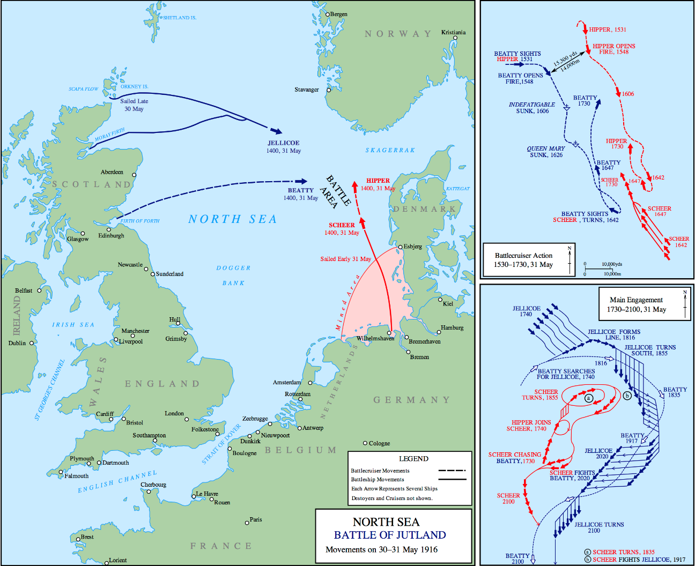

Since the British were not maintaining a tight blockade of the German coastline where they would be vulnerable to a sortie, Scheer planned to use his light forces to draw the British fleet out piecemeal by attacking coastal towns with destroyers, cruisers and zeppelins, forcing the Royal Navy to defend its homeland. After months of trying to tie an operation together that put the German fleet in a superior position, on May 31st, 1916, the German battlefleet including sixteen of Germany’s eighteen dreadnoughts set course to the north. The German sailors wondered, would today be der tag, The Day, that the fleet had been waiting and building up to for years?

But, here, already the German plan was falling apart, although they did not know it yet. The reason for the German sortie was to provide the bait for a submarine ambush. Two weeks earlier, German submarines, which had been recalled from unrestricted submarine warfare earlier to prevent the Americans from entering the war, had been stationed outside major British naval bases to ambush the British fleet which would sortie in response to the German fleet. The submarine force here failed. The mines they laid did not strike a single British ship, no torpedoes were launched at the British, and they even failed to provide useful warning of British movements. The 150-ship British Grand Fleet under Admiral John Jellicoe, eager to vanquish the German threat, was converging on their position, and Scheer had no idea. The stage was set for the battle where the British had all of the advantages: more ships overall, 28 dreadnoughts to the German’s 16, more heavy guns, bigger guns, and a 2-knot speed advantage.

On an intercept course for the German fleet but not finding them quite where they expected, the British began to doubt their intelligence. Many of the old-line Royal Navy officers looked down on the intelligence and codebreaking civilians who worked for them. One captain, crucially on the morning of the 31st, failed to grasp or ask the right questions from his signals intelligence subordinates, dismissing them as “a party of very clever fellows who could decipher coded signals,” which happened to, yes, be true but not in the pejorative way that the captain meant it. Had the British used their intelligence assets who had broken the German naval codes years ago, they could have intercepted the German fleet about two hours earlier, which would have allowed for two hours more fighting before dark fell. But, as it were, at 1420 on May 31st, 1916, the forward elements for the British screen spied the toward elements of the German force through their binoculars, and just eight minutes later, the HMS Galatea fired the first shots of the Battle of Jutland at the German ships on the horizon.

Both forces signaled for “action stations,” or as it is called in the United States Navy, “general quarters.” Royal Navy Admiral David Beatty, in command of the British advance force, charged his ships towards the German advance force commanded by their Admiral Franz von Hipper. Admiral Hipper turned south to protect his rear. If all went according to plan, he hoped to draw the partial British force into the jaws of the main German High Seas Fleet coming up behind his advance force. The next hour is known as the Run to the South.

The Run to the South

At 3:45, 16,500 yards from Hipper, Beatty swung his six battlecruisers ships into a line of battle. Battlecruisers are basically fast and lightly armored dreadnoughts, usually used to scout out the position of the main enemy fleet. With far superior local firepower, Beatty felt he could not help but demolish the isolated Germans. And yet, it is a historical mystery why Beatty took so long to engage. His ship’s 13.5-inch guns outranged Hipper’s 12-inch and 11-inch guns by several thousand yards and Beatty could have opened fire long before Hipper was able to reply. Instead, the British closed quickly without firing and Beatty denied himself several unopposed salvos. Finally, at the range of sixteen thousand yards, both forces opened fire on each other simultaneously. The Run to the South had begun.

German salvos proved as effective as Admiral Scheer had hoped. Well trained German crews, assisted by better range finders and gun sights as well as favorable environmental conditions, began scoring hits immediately on their British opponents from the range of eight miles, while returning British fire sometimes fell as much as three miles off its mark. Admiral Hipper, with a cigar clamped between his teeth on the bridge of his flagship, commanded calmly and ruthlessly. Officers there that day recalled “His unruffled calm [as] work was carried on exactly as it had been in peacetime maneuvers.” Geysers of water a hundred feet high announced misses, and on both sides the accuracy was now good enough that sailors were being soaked. Ten minutes into the engagement, with the range down to 13,000 yards, the British scored their first hit on the German fleet, and four minutes later, their second. Blood now mixed with seawater on both sides.

Just minutes later, the German Von der Tann, which had been laying murderous 11-inch shell after murderous 11-inch shell into the British battlecruiser Indefatigable, sank the first ship of the Battle of Jutland. Wracked by secondary explosions, the Indefatigable blew literally in half, with huge pieces of machinery and armor flying 200 feet into the air. Of her crew of 1,019, only three survived.

Allowing the range between the squadrons to open to 18,000 yards- beyond the range of either force- Beatty allowed four Queen Elizabeth class battleships to catch up to his advance force. These ships were super-dreadnoughts, the pride of the British fleet. Fast and armed with massive 15-inch guns, the Germans saw these steel beasts coming and Hipper knew that his screening force, better gunnery or not, was now colossally outmatched. At a range of 19,000 yards from which the Germans could not respond, the British super-dreadnoughts paralleled Hipper’s course, swung their gun turrets to port, launched salvos of 15-inch shells down on the rear two German battlecruisers, landing in the water so close to their marks that the German hulls “quivered and reverberated.” The next salvo struck the Von der Tann with 1,920 pounds of steel and explosive, ripping through her underwater armor and flooding her after compartments. Then it was the Moltke’s turn as accurate shells devastated her as well. To escape destruction, the two rearmost German battlecruisers began to zigzag, sacrificing any hope of returning accurate fire in hope of throwing off the British rain of death.

As the distances closed, the five British battlecruisers also began to engage Hipper’s entire line of retreating warships. In their retreat, suffering heavy damage the whole way, Hipper’s outgunned men somehow managed to land five shells in rapid succession on the HMS Queen Mary, one of Beatty’s battlecruisers, sinking her with the loss of all but 18 of her 1,300-soul crew. But the British assault remained unphased. In the words of a British officer on the HMS New Zealand, “This second disaster was rather stunning, but the only signal coming from the flagship was, ‘Battle cruisers alter course two points to port’—that is, towards the enemy.’” The British sent 30 destroyers charging into the German line for a torpedo attack, which was countered by German destroyers screening their capital ships in what became a scrum, with torpedoes and shells from the destroyer’s 4-inch guns flying in all directions in the no-mans-land between the two lines of capital ships.

After 20 minutes, Beatty recalled his destroyers. As the British destroyers turned back, their captains saw something they could not believe: Beatty and his battle cruisers were reversing course and heading north. Apparently, Beatty was running away. Although he cut a heroic figure, soaked in the salt spray and with shrapnel clanging around him on the exposed bridge of his damaged flagship in the Run to the South, in the first phase of the Battle of Jutland, Beatty clearly lost to Hipper. The German admiral commanded an inferior force but had sunk two British battle cruisers and two British destroyers at a cost of only two German destroyers. Hipper’s position was still perilous, but the German plan was succeeding in bringing the unsuspecting Beatty ever closer to the sixteen dreadnoughts of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet. Now, just as the British were disengaging, Hipper at last saw on the horizon Scheer’s long, pale gray column. Seeing that the tables had now turned, Hipper swung his battle cruisers north again and took up his normal battle position at the head of the northbound High Seas Fleet.

But when Beatty received news of the German fleet, he did not panic. He instead smiled as he recognized the opportunity here. With luck, he could pull the same tactic the German had tried to use on him and lure the High Seas Fleet into an ambush. The German Admirals Hipper and Scheer had no idea that the full might of the British Grand fleet was behind him and if he could lure the Germans too far north it would be a massacre, just not the massacre the Germans had planned.

And so here we have British Admiral Beatty retreating north towards the bulk of the British fleet with the Germans confidently chasing him until, at 6pm, reports arrived that must have shaken even veterans Scheer and Hipper to their core: the Grand Fleet was sighted on the horizon. Twenty-four British dreadnoughts and their more than 100 screening cruisers and destroyers only 16,000 yards away, making towards them at 20 knots.