My fellow Americans:

As President and Commander in Chief, it is my duty to the American people to report that renewed hostile actions against United States ships on the high seas in the Gulf of Tonkin have today required me to order the military forces of the United States to take action in reply.

The initial attack on the destroyer Maddox, on August 2, was repeated today by a number of hostile vessels attacking two U.S. destroyers with torpedoes. The destroyers and supporting aircraft acted at once on the orders I gave after the initial act of aggression. We believe at least two of the attacking boats were sunk. There were no U.S. losses.

The performance of commanders and crews in this engagement is in the highest tradition of the United States Navy. But repeated acts of violence against the Armed Forces of the United States must be met not only with alert defense, but with positive reply.

What you just listened to was an excerpt of the August 4th, 1964 press conference given by President Lyndon Johnson reporting on the so-called Gulf of Tonkin incident. That first minute or so (you can read the full transcript here) was the exact moment which would usher in an era that would change the lives of millions of Americans, Vietnamese directly, and the fabric of American society as a whole.

After that press conference announcing what was believed to be an attack on the destroyer USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy, the already unpopular Vietnam War began in earnest. And as with any war, it tested the will, bravery and the endurance of millions of Soldiers, Airmen, Marines and what we'll be paying specific attention to - Sailors over the course of the next 11 years of conflict.

Almost 3 million American men and women served in Vietnam. 58,000 would go on to lose their lives. The U.S. Navy deployed 1.8 million sailors and got off proportionately lightly, suffering "only" 1,631 dead and 4,178 wounded. The Navy deployed a new force in the Vietnam Era. Between the end of the Korean War and the start of the Vietnam War, the US Navy introduced an all-jet carrier air wing, including the F-4 Phantom II and Crusader, whose pilots dueled with MiG fighter pilots over the skies of Vietnam, and A-4 Skyhawks capable of all weather, low level ground attack, paired with new 3D radars and advanced missiles. The early results nonetheless ended in discouraging draws in the air against Soviet produced Vietnamese piloted MiGs.

Naval aviation roared back with a vengeance after a lull in the fighting between 1968-1970, thanks to the Top Gun training program and a EA-6 Prowlers, which brought advanced electronic attack and jamming capabilities to bear against the air defenses around Hanoi, which were among the best in the world, rivaling even those of the Soviet Union deployed around Moscow. On the ground, Special Forces teams developed the foundational tactics of hit and run night raiding behind enemy lines that are still in use today. I'm going to cover all of these topics and more by the end of the two Vietnam War posts.

But before the fighting reached its relentless peak during the late 1960s, early operations meant supporting the South Vietnamese troops, resisting the Communist Army, training Vietnamese sailors and ensuring the ammunition supplies reach the armies fighting in South Vietnam.

There's no clean, distinct line separating brown water and blue water operations. But this at least, keeps it manageable. We're really emerging now into the modern, documented era of warfare with Vietnam, and there's a lot of material to draw in from this era. And I think I hope that you're really going to enjoy these next two posts.

So what is Vietnam? The question has a lot of different answers depending on who you ask. President Trump called avoiding STDs during his single years his personal Vietnam. I suspect that the veterans who lived through it would disagree. And although the Vietnam generation of veterans are getting up into their seventies and eighties, there are still plenty who remember and can tell you their stories, which it seems like more often than not they would prefer to forget.

Today, the Vietnam War, just like every other war before it after a generation or two has passed, has been reduced to a few iconic images in the popular imagination. For World War Two, it was billowing black clouds of smoke pouring from the sinking Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor, the landings at Normandy, recently liberated Nazi death camps and atomic mushroom clouds. When talking to people my own age about the Vietnam War today, the dominant images seem to be napalm burning through rice paddies and patches of jungle, women and children running away with expressions of loss and pain on their faces. And equally as salient, the counterculture the war spawned at home.

But at the time, before the 1960s, I'd bet as few Americans could place Vietnam on a map as Americans who could place Afghanistan pre-9/11. Which is to say, not many at all. Bill Eckhardt, U.S. Marine Corps veteran and recipient of the Purple Heart, admits the naivete with which he and his fellow Marines arrived in Vietnam.

Well, when I got to Vietnam, I literally expected to be welcomed with open arms by the people of Vietnam. I had in my head the black and white newsreels I had seen on the Walter Cronkite Twentieth-Century show of the American troops rolling through villages in France and being showered with wine and flowers and kisses. And as we were driving down a guy from the battalion, I was assigned to pick me up in a jeep at Danang and we had to drive the 20 miles to where my battalion was located. And I really was disappointed that there weren't people standing along the road waving to me and, you know, offering me flowers and things. I really expected to be greeted with open arms as a liberator. And it was it was as though I was invisible that I didn't exist. And that was a little perplexing. At the time, he had no idea why the people weren't happy to see U.S. soldiers and why many of them hated us.

What he didn't know was that to the people of Vietnam, he represented just a continuation of the French colonial occupation, which had started in 1858.

The Leadup to the Vietnam War

Fighting in Vietnam had been ongoing for much longer than much longer than the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. It's been going on for more than a decade by the time Lyndon Johnson announced the first major escalation of U.S. actions in the peninsula, and would go on for years after the last American soldier was extracted from the country, as Vietnam occupied neighboring Cambodia in 1978 and a border war with China in 1979. All of which is to say that Vietnam had a turbulent couple of decades right after the end of World War Two.

The Viet Minh, a communist led anti-imperialist party and army led by Ho Chi Minh, claimed control of almost all of the country in a power vacuum immediately after the Japanese surrender. A year later, in 1946, the revived French government sent troops back to occupy its former colony of Vietnam and crush Ho Chi Minh's new government, forcing his military to abandon the cities for the jungles, mountains and countryside. Initially, the Vietnamese resistance was organized as a guerrilla force, but it slowly coalesced into an increasingly capable and larger standing units with the support of the neighboring People's Republic of China fresh from its victory over the Nationalists in 1949.

Based on anti-colonial principles, the United States had initially opposed the French recolonization of Indochina. But the victory of the communists just north of Vietnam in the Chinese Civil War drove the Truman and Eisenhower administrations to support the French in the war against the Viet Minh. By 1950, the US sent the first 35-man strong Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to assist the French. They would go on to provide extensive financial assistance and air power support for the French colonial forces.

Nonetheless, four years of warfare later, the Viet Minh achieved an incredible victory at Dien Bien Phu where the Vietnamese overran a French stronghold in the North Vietnamese mountains on the Lao border, following a 55-day siege in between March and April of 1954. This defeat precipitated the fall of the French government back in mainland France and effectively put an end to what was known as the First Indochina War.

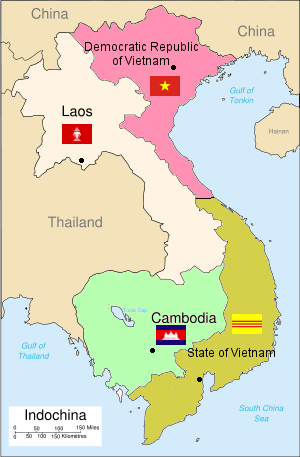

On July 21st, 1954, Ho Chi Minh attended the Geneva Conference, whose main objective was to settle the territorial issues in both Korea and in Vietnam. There it was decided that the French would forego their claims to Vietnamese territory and the country would be partitioned along the 17th parallel, with the ironically named Democratic Republic of Vietnam under communist rule to the north of the parallel, whose capital would be Hanoi and the western aligned state of Vietnam to the South, whose capital was Saigon.

Immediately following the Geneva Accords, the Navy began its first large scale operation in Vietnam - Operation Passage to Freedom, which transported close to a million North Vietnamese refugees from North Vietnam to be relocated in South Vietnam. The operation was executed under the command of Rear Admiral Lorenzo Southern, an experienced commander who had directed amphibious operations on Omaha Beach on D-Day back in World War Two. The soldiers and civilians transported during the yearlong grace period before the border was sealed proved to be a formative event for the still relatively new military transport service headquartered in Washington, DC, which oversaw four regional commands. The Far East Area Command, located in Yokohama, Japan, was responsible for the war effort in Vietnam, which was over 2000 nautical miles away from Hanoi, with the Chinese then between doing their best to act as the spoiler.

President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam claimed power in a blatantly tampered with election in 1955 and with the help of American advisers, began developing a national army, police force and government bureaucracy from the ground up. He also built out an incredibly oppressive and ruthless security apparatus (think secret police). The internal security force was very effective, and managed to find and destroy most of the communist-aligned anti-Diem coalition, along with a huge number of innocent civilians in its quest to destroy the National Liberation Front and its armed wing, the People's Liberation Armed Forces. Or, as there are more widely known as one of the main villains of this story, from the American perspective, the Vietcong, a term which roughly translates into "Vietnamese Communist traitor" and a masterpiece of branding by the Diem regime.

As mentioned, Diem's Secret police were pretty darn effective. The Viet Cong were desperate and on the verge of being wiped out by the Diem regime. The southern leadership begged Ho Chi Minh, who lead the North Vietnamese government, for help. The leadership in Hanoi was initially reluctant to help because the communist economic reforms of the past few years have been predictably disastrous, leading to significant problems on the homefront. But the regime finally relented and agreed to reignite active warfare in January of 1959.

The Kennedy Escalation

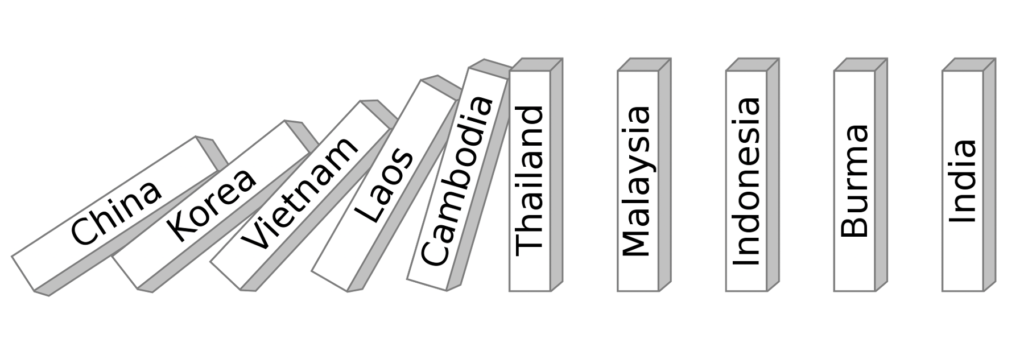

So at this point, the new Kennedy administration was convinced that the renewed warfare was part of a general communist offensive worldwide. Kennedy invoked his doctrine of flexible response to begin what was the first of many military escalations in Vietnam. This first escalation increased economic aid and the number of U.S. troops in Vietnam from an Eisenhower-era high of 900 to 16,000 men overseas. Kennedy intended to keep this number hidden from the already skeptical public. As with Korea, the U.S. assumed responsibility for the southern state, vowing to stop the spread of communism wherever in the world it presented itself. Containment and the domino effect were two expressions that poured a lot in the media at the time following the worrying dispersion of communist ideas and governments in the so-called Third World.

At the same time, the experience in Korea from 1950 to 1953 taught the government in Washington that the people were tired of war, and that sending troops to a foreign country to liberate it was unthinkable. They would have to be sensible and intelligent about this whole Vietnam crisis.

Building the South Vietnamese Navy

The story of the U.S. Navy in Vietnam starts in the fall of 1950, when the first U.S. Navy advisers arrived in South Vietnam to assist the new republic in building a navy of their own. This is part of the task force created by President Truman called the Military Assistance Advisory Group, or MAAG (if you remember the acronym), to help the South Vietnamese armed themselves and defend their country.

These advisers helped develop the Vietnamese Navy from scratch. After France retreated from Vietnam, they agreed as part of the Geneva Peace Accords of 1954 to transfer a total of 22 small craft and prepare the Vietnamese navy. The Vietnamese navy had few sailors prepared to sail these craft, let alone make necessary repairs. And under the threat of a communist offensive from the North, this fleet was almost useless.

The American MAAG initially developed the South Vietnamese navy from 2,000 sailors drawn from the local fishermen to man the ships. Thanks to the MAAG, the number would explode in the following years. By 1959, the RVNN (Republic of Vietnam Navy) had 5,000 sailors manning 122 vessels, many of them converted World War Two landing craft. By 1972, when conventional American forces had pulled out of Vietnam, American advisers could boast that they had built up the South Vietnamese navy into the fifth largest navy in the world, with over 42,000 men and 1,500 vessels in service. Naval advisors worked throughout the war to train the local navy under less than ideal conditions. Many of these advisors lost their lives serving on defense ships and small craft.

The first step taken by the newly created Vietnamese navy was to assemble a fleet of junks the traditional sailing ships of Asia, made out of soft woods and bamboo to cover the 1200 miles of coastline and pay local, experienced fishermen to man them. This fleet of about 600 specially built wooden junks will later be known as the coastal groups. And although hardly a force to be reckoned with during those initial years, it served its purpose, which was to provide some basic coastal security and surveillance.

During the Kennedy years, the MAAG was responsible for increasing the strength of the Vietnamese navy from 5000 officers to 8000. The objective was to leave the country as soon as possible and well on that score. Woops. Little did they know the following years at see the US Navy not only training Vietnamese sailors but fighting and dying in increased numbers alongside them.

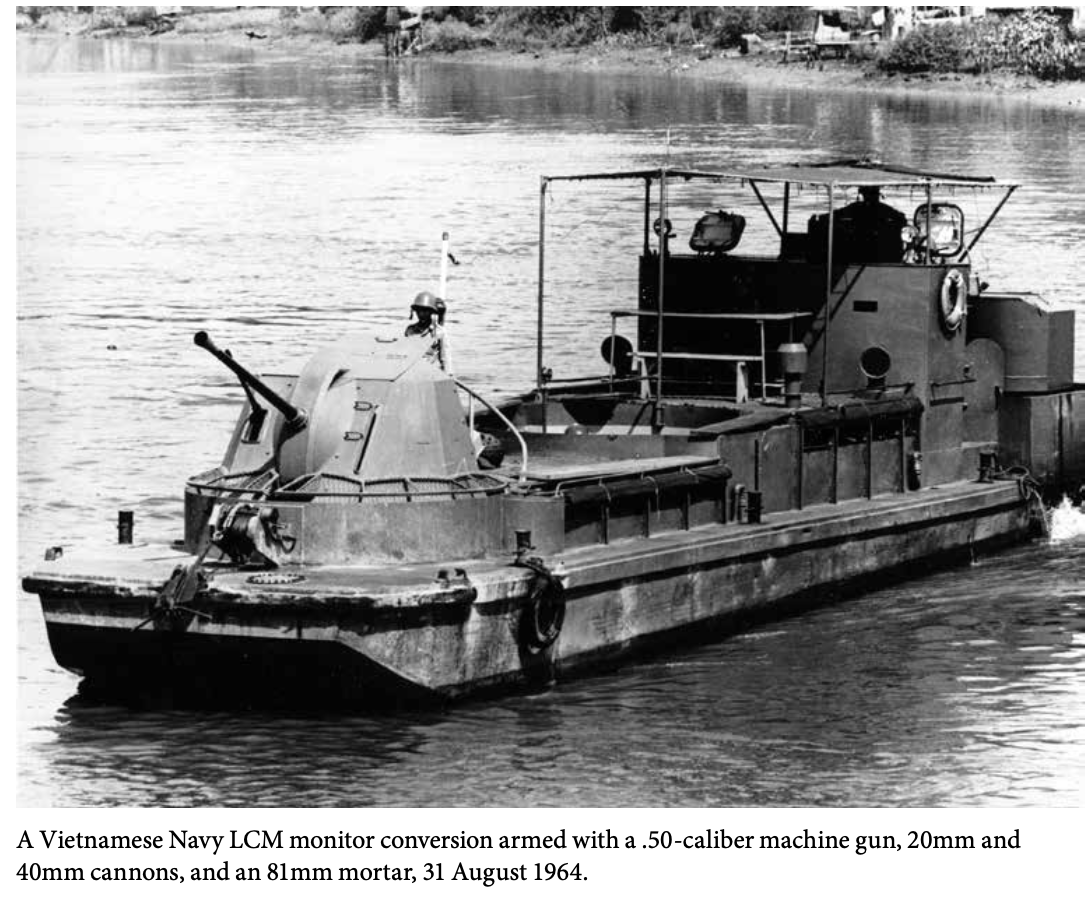

By late 1964, the United States was supporting a Vietnamese naval arm of 44 seagoing ships and over 200 landing craft patrol ships and other vessels. Apart from the junks which made up for in quantity and local knowledge of their crew, but they lacked foreign quality. The VNN was composed of previous US Navy owned patrol craft escorts or PCs along with motor gun boats, large support landing ships, large and medium infantry landing ships and tank landing ships.

What the Vietnamese lacked in technology and equipment they made up for in ingenuity. They learned from the French tactics of fighting the Viet Minh from the rivers and added ideas of their own to form river assault groups. RAGs consisted of armored landing craft, which they used to transport troops, escort convoys of rice boats, sweep for mines and provide gunfire support to ground units. We'll discuss the RAGs in more detail in the next episode, focusing on brown water operations. But I just want to point out that the Vietnamese did, in fact, operate a fairly proficient naval force, which was able to impose a measure of control on the almost roadless Mekong Delta.

Now that was all well and good. And the advisers were enthusiastic and the Kennedy administration was doing a good job in supporting the counterinsurgency in South Vietnam. But this would all change in November of 1963.

The LBJ Era

Among the many things historians don't like to answer are what if questions? And one of the biggest what ifs in Cold War history is what if Kennedy had not been assassinated and had finished his term? Would anything have changed regarding the Vietnam War? Vietnam itself? Can everything that happened later, including the 58,000 American deaths in Vietnam, depend on LBJ?

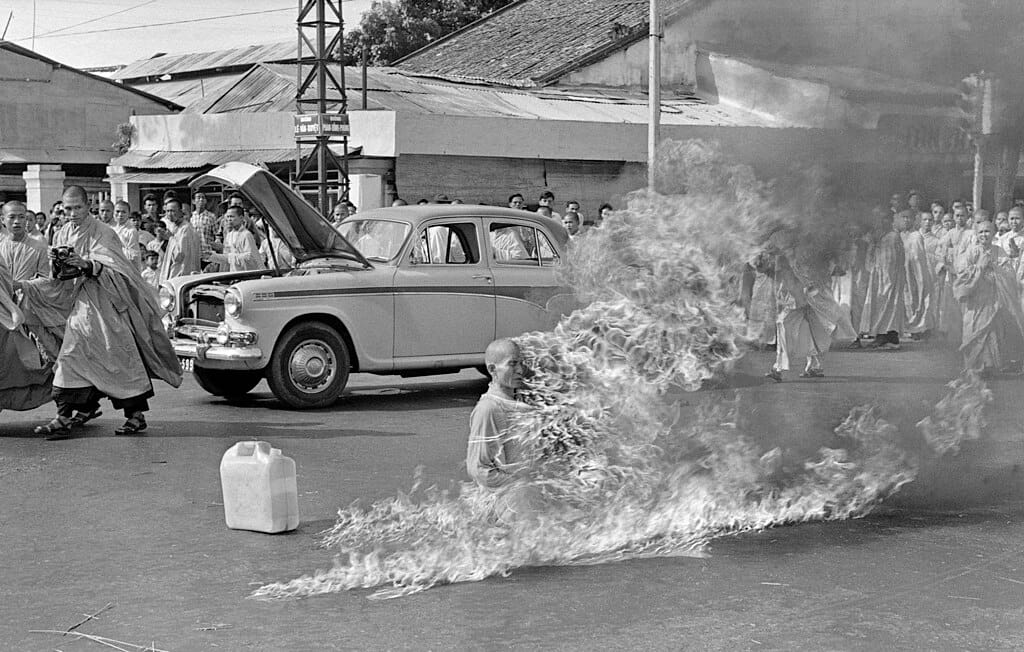

Well, 20 days before his tragic visit to Dallas, President Kennedy received troubling news from Vietnam. President Diem, whom he had backed on many occasions, was dead, as was his brother. They were killed not by the Vietcong, the armed guerrillas who took orders in North Vietnam, not by the North Vietnamese Army, but by South Vietnamese soldiers, tired of the autocratic style of government. Diem, a Catholic ruling over a country where 80% of the population were devout Buddhists, had banned the use of the Buddhist flag and was targeting Buddhist monks and institutions. The subsequent images, a monk setting themselves on fire and protests are seen by millions around the globe.

The people and military of South Vietnam were similarly unhappy with the poor results the government had had in fighting the Viet Cong insurgency and felt the president and his entourage were corrupt (which, to be clear, they were) and intended to amass dictatorial powers.

The first victim of the coup was Captain Houghton Tuan, the commander of the Vietnamese Navy. On November 1st, 1963 he was celebrating his 36th birthday. There are several conflicting accounts of his demise, but apparently he became aware of unusual troop movements and suspected a coup was about to take place. Just before noon, he jumped on a jeep and set off towards the palace to warn President Diem of the situation. He was intercepted enroute or convinced to stop the car, and then someone here, some sources claim it was his deputy shot him point blank in the face.

So after that, president Diem and his brother were assassinated. The South Vietnamese government fell and a period of turmoil was unleashed. But most people agree that, at least for the Vietnamese, the future looked brighter than during the Diem years. 20 days later, Kennedy was shot in Dallas. Vice President Lyndon Johnson inherited an uncontrolled situation in Vietnam that would only get worse for the United States and our Navy.

Nonetheless, the Cold War was supposed to be exactly that - cold. So the United States refused to get involved past the already mentioned merchant transportation and naval advisory tasks. Unless that is, we were attacked first. And sure enough, as it happened during World War Two, the United States would be "provoked" into a war in Asia.

On March six, the 1965, two days before the first two U.S. Marine battalions disembarked on mainland Vietnam at Danang, LBJ admitted in private the pressure he was under and his reservations about sending the Marines in to protect U.S. airbases in Vietnam.

"So we're going to send the Marines to protect the 'Hawk Battalion, the Hawk outfit at Da Nang , because they're trying to come in and destroy there and they're afraid the security provided by the Vietnamese is not enough."

Johnson felt like it was a bad situation where he had no good choices, and:

"I guess we got no choice, but scares to death out of me. I guess we landin' the Marines, we're off to battle, ... it's just if they come up there they're going to get'm in a fight, as sure as hell, then you're tied down. And if they don't go and they get those airplanes are everybody's going to give me hell for not secure in them, just like you did last time they made a raid."

"Yeah. So it's a choice, and it's a hard one. But Westmoreland and Taylor come in every day saying, 'Please send them on', and Joint Chiefs say, 'Please send them on,' And McNamara and Russ, they 'send them on.'"

But regardless of having a choice or not, the die was already cast. America was going to war, and the U.S. Navy had to prove that it was up to the task.

North Vietnam gets aggressive

In the wake of President Diem's assassination, North Vietnam accelerated the movement of men and material into South Vietnam, both via sea lanes and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which is the North-South corridor that traversed eastern part of Laos and Cambodia, parallel to the Vietnamese border. The Ho Chi Minh Trail would eventually bring millions of tons of food, military supplies and hundreds of thousands of fighters infiltrating into South Vietnam.

Alarmed by this development, the last time Prime Minister authorized the United States in May, 1964 to conduct low level aerial reconnaissance to gather intelligence on the North Vietnamese presence in this country. A joint Navy and Air Force operation team was created on the 18th. Aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk, CVA-63, and her task group immediately deployed to the Yankee Station off the coast of North Vietnam in the Gulf of Tonkin. Just a few days later, Navy-Marine Corps RF-8A Crusader and RA-3B Skywarrior reconnaissance planes began executing missions over Laos. On May 21, two RF-8A Air Reconnaissance Planes Launched from Kitty Hawk for the first Navy mission. Gunfire from North Vietnamese forces during the mission put bullet holes in one plane and set it on fire, but the pilot managed to land safely on the Kitty Hawk.

By 1964, American leaders had become increasingly concerned about North Vietnam's sponsorship and support of the guerrilla conflict in South Vietnam and the possibility of a declared war, instead of the current status quo of insurgency operations, infiltration and border skirmishes. But furthermore, they didn't know the number and position of the coastal defenses of North Vietnamese garrisons. President Johnson ordered the Navy to conduct intelligence gathering missions known as DESOTO (convolutedly named after the first destroyer to conduct the operation, the USS DeHaven, thus: DeHaven Special Operations off TsingtaO) Patrols in the Gulf of Tonkin.

DESOTO Patrols

The DESOTO patrols had been in far more limited existence since 1962. They were composed of destroyers equipped with special intelligence gathering equipment and technicians capable of intercepting and deciphering signals intelligence, sailing up and down the coast of China, parts of the Soviet Union, North Korea, and now North Vietnam. In these dangerous missions, the ships are not cleared to approach more than 20 miles from the coast.

Destroyer USS Maddox embarked to support a DeSoto Patrol mission in the Gulf of Tonkin off of the North Vietnamese coastline on August 2nd, 1964. Communications technicians aboard the Maddox informed Captain John Herrick that the North Vietnamese were tracking and preparing an attack on unspecified enemy offshore. Soon after, he learned that the North Vietnamese were concentrating a force of four torpedo boats off the island of Hon Me with the apparent intention of intercepting the destroyer as she moves south between the island and the Vietnamese coast. Captain Herrick decided to change course, steering away from the shore. This maneuver made it more difficult for the P-4 force to engage Maddox while at the same time the carrier Ticonderoga launched four F-8 Crusader jet fighters to provide air cover.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

Around 1600, the Maddox's radar detected three North Vietnamese boats just five miles away and zeroing in on the Maddox at high speed. The Maddox opened fire with their three and five inch guns. Under heavy fire, the North Vietnamese boats launch four torpedoes towards the Maddox, two of which came within several hundred yards of the Maddox, which by this point was taking evasive action. The Maddox continued to pour fire into the enemy boats and hit one with a five-inch shell, inflicting heavy damage. The birds returned fire, hitting the Maddox with 14.5 millimeter shells before turning back towards the coast. Just as the Ticonderoga Crusaders, led by Commander James Stockdale, future POW, war hero, and vice presidential nominee, attacked the fleeing craft, damaging all three of them.

The news of this attack was transmitted up to the chain of command to President Johnson, who chose not to retaliate further, but sent a warning to the Vietnamese that further provocations would not be taken lightly. The tense crews of the Maddox and Ticonderoga resumed their patrols a few miles farther away from the North Vietnamese coast.

Two days later, on the night of August 4, the destroyers Maddox and Turner Joy both detected on radar a number of small, fast-moving surface vessels moving towards them at high speed. Both Captains ordered their crews to open fire on the suspected inbound attackers while sonarmen reported the acoustic signatures of inbound torpedoes in the water. Sailors on deck and on the bridge reported machine gun flashes in the night and sailors on the Turner Joy swore they saw the outline of a boat illuminated by one of the phosphorous flares launched by the destroyer to illuminate the battlespace. Jets roared off the deck of two nearby carriers and circled overhead, but were unable to identify any enemy aircraft amid the low heavy cloud cover and sea fog. The Maddox and Turner Joy continued to maneuver at high speeds with their deck guns blasting away into the fog in the direction of the detected boats. By 0100 hours, the previously identified radar signatures had vanished.

Initial situation reports sent by the destroyers claimed six North Vietnamese boats sunk. But as the search for wreckage and battle damage in the light of the next day failed to turn up any debris, the CO of the Maddox expressed doubt in official messages to the carrier task group CO. But by that time, the initial reports of the attack were transmitted to President Johnson, who now had to make a decision.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident was pivotal for U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Now, 60 years later, we decisively know that there was no second attack by North Vietnamese naval units on the night of August 4, but neither was there an intentional fabrication, as some have claimed since. Instead, a combination of fragmented and confused signal intelligence that was not subjected to thorough analysis (amid the other failures), and already tense situation led Johnson to erroneously conclude far too quickly with far too much certainty that the Navy had been attacked again.

In response, President Johnson ordered the carriers Ticonderoga and Constellation to launch retaliatory bomb strikes on August 5th against North Vietnamese targets both ashore and afloat, destroying boat bases and oil storage facilities. The air crews suffered the first of many aircraft shot down in the war as two of the 67 planes which took part in the raid were brought down by North Vietnamese air defenses. Lieutenant Junior Grade Everett Alvarez became the Navy's first of many downed pilot P.O.W.s.

More importantly, on August 7, the House of Representatives and the Senate almost unanimously passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, allowing President Johnson to deploy conventional military forces to fight the Vietnam War.

A Resurgent Navy off the Coast of Vietnam

With the U.S. Navy now fully committed to the war in Vietnam, control over inland and open waters improved significantly. This meant more supplies, more fire support, and more reconnaissance capabilities. Last but not least, cutting the enemy supply lines. This would prove crucial thanks to a surprising discovery made in early 1965.

In the six months after the Gulf of Tonkin crisis, the Navy had reinforced Seventh Fleet with an attack carrier, ten destroyers, three submarines, and one tank landing ship with ten more units planned. The Navy also doubled the number of aircraft in the fleet replacement pool and deployed a squadron of P-3 Orion patrol craft to the Philippines. Ships from the National Defense Reserve Fleet were reactivated from their mothballed status, and merchant ships were chartered.

If the Navy needed another reason to get ready for battle in South Vietnam, apart from the attacks suffered by the Maddox in August, the reason presented itself on February 16, 1965. Early that morning, a U.S. Army helicopter patrolling the Central Coast of Vietnam spotted at Vũng Rô Bay what appeared to be a large camouflaged ship perpendicular to shore, being offloaded and stacked on the beach.

Lieutenant Commander Harvey Rogers, senior advisor to the South Vietnamese Second Coastal District, was immediately informed of the sighting. He in turn notified the coastal district commander, Lieutenant Commander Ho Van Khai Toi. South Vietnamese A1 Skyraiders were soon dispatched to Vũng Rô Bay and a swift bombing sunk the ship. This was followed by additional airstrikes on the beach. The next day, and on 19 February, South Vietnamese troops disembarked at Vũng Rô securing the beach and the wreck of the camouflaged ship.

U.S. naval historian Edward Marolda describes what followed: "But the soldiers and commandos, later, accompanied by U.S. Naval advisor Lieutenant Franklin Anderson, discovered in the wrecked ship and piled up on the shore, ended a long running debate among the U.S. military intelligence officials. The allies recovered from the 130-foot North Vietnamese ship and from shore sites, 100 tons of Soviet and Chinese made war material, such as 3500 to 4000 rifles and submachine guns, 1 million rounds of small arms ammunition, 1500 grenades, 2000 mortar rounds, and 500 pounds of explosives."

Smuggling Weapons into Vietnam by Sea

American analysts had been debating for years if the Vietcong fighting in South Vietnam were supplied solely via the Ho Chi Minh Trail or also by sea. Now, they knew for sure that Soviet and Chinese supplies entered the territory by sea.

The discovery of the trawler at Vũng Rô Bay in February of 1965 led to the establishment of a US Naval and Coast Guard patrol force to complement the existing Vietnamese Navy Anti-Infiltration Program along the 1,200 miles of southern Vietnamese coastline. The purpose of this deployment, which was later dubbed Operation Market Time, was to stop the seaborne infiltration of supplies to the Viet Cong. The smuggling had been going on since the French era, but the involvement of the Americans had redoubled Chinese and Soviet support for the Viet Cong. Now thousands of tonnes of material per month were flowing from North Vietnam to South Vietnamese Viet Cong insurgents in junks, fishing vessels, small coastal trawlers and thousands of other small craft.

These unflagged small vessels, many built in China for just this purpose, would only carry a few tons of supplies each and depart from North Vietnam before sailing east into the international waters of the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. Until they believed that they had evaded South Vietnamese and American surveillance for taking a sharp turn in nighttime sprint toward the South Vietnamese coastline, where they could offload their 100 to 400 tons of cargo at sea into smaller sampans and fishing junks, which were indistinguishable from any of the other thousands of similar small craft. Or they could disappear directly into one of the thousands of mangrove swamps, tiny inlets, rivers or beaches where their cargo could be offloaded directly.

Operation Market Time

The offload region was described by then Vice Admiral Zumwalt, commander of Naval Forces Vietnam, as, "a place of streams and mangrove swamps. Hard to get to and even harder to get into." From these inlets, swamps and streams, the Viet Cong travelers would be met by local guerrilla fighters to offload the cargo of weapons, ammunition and other war material, which would then in turn be loaded into even smaller vessels and smuggled through the maze of natural and irrigation canals in the Mekong Delta wetlands of Vietnam.

Operation Market Time represented the Navy's most successful interdiction program during the Vietnam War, significantly cutting down on infiltration by North Vietnamese trawlers and dramatically reducing the supplies that reached the communist insurgents in the South. The Navy utilized the combination of shore-based surveillance centers, aerial surveillance, Coast Guard cutters, ships and small patrol craft (notably swift boats) to interdict and search for the North Vietnamese craft before they sprinted for the coast and could get lost among the heavy coastal traffic and inland waterways of South Vietnam.

The scope of Market Time grew over time. American and South Vietnamese crews boarded thousands of suspicious vessels. Few vessels actually smuggling supplies surrendered without a fight, and firefights between the crews were common with American professionalism in training, .50 caliber machine guns, rockets, grenade launchers and the air and destroyer backup if necessary, almost always resulting in the sinking or capture of the enemy vessel, although often with American casualties in the process.

The scale of the operations grew hugely. In 1966 alone, Allied forces detected 808,000 watercraft visually inspected 223,000 of them, boarded 181,000 and engaged in a total of 482 firefights. General Westmoreland estimated that before launching Operation Market Time in 1965, the Vietcong in South Vietnam received 70% of their supplies by sea, which was reduced to 10% by the end of 1966.

The effectiveness of the operation was mixed. Market Time did force the North Vietnamese to change their logistics routes and rely much more heavily on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which we then bombed relentlessly later in the war. The coordination between the aerial surveillance and the seaborne interdiction was the essential component. But it's hard to tell exactly how effective the operation was, how many craft really slipped through undetected, and how to compare the effect of the operation to the enormous cost that it took to implement and the antagonism that it generated among the local innocent population who were mostly just trying to make an honest living fishing or trading up and down the coast.

Vietnam War Strategy...such as it was anyway

The U.S. military, which first deployed in significant numbers to Vietnam in 1965, was a product of the 1950s Eisenhower military doctrine, built around the concept of massive retaliation to the communist threat. It was designed as a huge conventional force to wage war against other modern conventional armies (aka the Red Army). The shifting nature of the war in Vietnam in 1965, from a small advisory and counterinsurgency force into a war which imported the U.S. Army in bulk, was a hard transition.

The theater commander, General Westmoreland, like the Army he led, was a product of WWII and the Korean War and unable to formulate a non-conventional strategy to deal with what was still a primarily unconventional fight. Westmoreland's grand strategy had two parts. First the plan was to build a huge series of logistical bases in the jungle highlands of Central Vietnam. Then, from these bases United States Army could (in theory) command the surrounding valleys with artillery power from hilltop fire bases and allow Army units to conduct large scale search and destroy missions in the surrounding villages while relying heavily on helicopters to provide logistical support and maneuverability for tens of thousands of soldiers deployed into what was essentially hostile territory. The helicopters would also be used to bring the battle and force to any North Vietnamese conventional units detected on the ground.

This extensive use of helicopters in hostile territory for transportation and resupply is a large part of the reason why the United States lost a horrifying 11,846 helicopters during the war, resulting in nearly 5000 American pilots and crew killed. To put this in perspective, those almost 12,000 lost helicopters is a little under three times the total number of helicopters across all branches of the United States military combined today, and 35 times more than the Soviets lost in Afghanistan. This just demonstrates you how rich of a society the United States was compared to our Cold War adversaries.

The South Vietnamese army was tasked with hunting down the Viet Cong in the more densely populated lowlands, while the United States would focus on stemming the flow of men and material into South Vietnam through a combination of aerial bombing and gunfire support on the coast. As the years went on, this task became increasingly futile, and the number of troops devoted to it swelled into hundreds of thousands.

Throughout the first phase of the war, the Marine Corps took a different approach, rejecting General Westmoreland's conventional approach and adopting at least some of the newer counterinsurgency theories developed in the past decade. Dubbed the "spreading inkblot", the Marine Corps approach focused on winning the support of the local population in a small area, hearts and minds in the 21st century parlance, kicking the enemy out and then slowly expanding the area of control. Utilizing small Combined Action Program, or CAP, teams consisting of a theoretical 13 Marine riflemen, 35 South Vietnamese militiamen drawn from the area that the CAP was operating in and a Navy corpsman working with the local population gave the Marine teams access to local language and knowledge. The strategy was successful to a degree, and there's been a lot of "what aboutism" in the decades since Vietnam, asking what would have happened if the Army had adopted these strategies as well. But most historians of the war would doubt that the end result would have changed at all.

The Air War

Following the Vũng Rô Bay sinking, LBJ ordered a bombing campaign against North Vietnam in March of 1965. Previous efforts proved unsuccessful, including the bombing of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, and sabotage operations along the coast of North Vietnam. The porous border and the Ho Chi Minh Trail made it impossible to effectively stop the flow of supplies with ground troops. And so the Johnson administration turned to the air war to interdict supplies flowing south, destroy the North Vietnamese war industry and attempt to break the will of the North Vietnamese to continue their aggressive reunification attempts.

The Johnson administration devised Operation Rolling Thunder as a way of deterring North Vietnamese support for the communist Viet Cong insurgents fighting against the South Vietnamese government. At the same time, the American intervention needed to be sufficiently limited as to not force the Soviet Union and China, both of which had atomic bombs by this time, from entering into the conflict and triggering a third great power war in less than 30 years.

The aerial bombardment would need to be both gradual and sustained, drawing a "line of thunder" in southern North Vietnam, which would gradually be rolled north ever closer to Hanoi, until at least the theory went, the North Vietnamese government was forced to capitulate and let South Vietnam take control of the unified country.

The ensuing three-year operation was the most intense air battle of the Cold War. It was by far the most difficult the United States has fought since World War Two. Two air wings launched over 150,000 around-the-clock sorties between March of 1965 and October of 1968 in support of Operation Rolling Thunder, while the Air Force launched a similar number from airbases in Thailand and Guam.

The scale of the bombing was amazing, but so was the resistance. The Soviet Union and China supplied very competent air defense networks to the Vietnamese - advanced radars, surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery, and very competent intercepting fighters. These missions were perilous. The Navy lost 382 aircraft over the skies of North Vietnam while dropping more than a million tons of bombs and an additional 4 million tons over contested parts of South Vietnam.

In 1968, retired Air Force officer Dennis Andrews published a book on the subject named "Rolling Thunder 1965: Anatomy of a Failure." Conclude what you will from the title. But suffice to say that Operation Rolling Thunder did not fulfill its strategic goal of forcing Ho Chi Minh to abandon his ambition to take over South Vietnam without requiring the U.S. to send ground troops into communist North Vietnam. It did however at least partially fulfill the objectives of destroying North Vietnamese infrastructure and independent war-making capability, and partially stemming the flow of material into southern Vietnam. North Vietnam paid a heavy price in terms of lost troops and damage to bridges, roads, power plants, etc... and became far more reliant on their Chinese and Soviet patrons, which presented a strategic lever the united States could use, since both of the communist great powers had other interests around the world that could be used to distract their attention on Vietnam.

Naval Aviation Lessons in Vietnam

For the U.S. Navy, which entered into the conflict with ships and aircraft that first saw service in Korea and with outdated aerial tactics, Operation Rolling Thunder taught several lessons. And in a few minutes, we'll talk about Operation Linebacker and see just how much the service learned from this experience, including through the establishment of the Top Gun Program in March of 1968, which operated for three years before the air war resumed in full.

Navy fighter pilots selected for the Topgun program were sent through an intense four-week training program on the F-4 Phantom II aircraft to improve their one-on-one aerial combat skills. After the disappointing results against the Soviet aircraft and Soviet-trained Vietnamese pilots during the Rolling Thunder years, when the air war resumed, the Navy's dogfighting kill ratio increased from a 2-to-1 ratio that was far worse than in World War Two or Korea to 12-to-1, with Topgun graduates scoring the majority of the Navy's air-to-air kills.

One thing that's been deeply criticized by analysts over the years was the extent to which Robert McNamara and President Johnson personally selected targets and gave orders from Washington, D.C., with little to no tactical understanding of the situation in Vietnam. Nowadays, the military is almost all too used to having staffers in the National Security Council micro-manage operations and issue orders from the White House to relatively low-level commanders in the Middle East. Thanks to modern communication technologies, it's almost as if they're there in the theater of operations. But this was definitely not the case in the 1960s. And despite all of the information that McNamara famously asked for to be reported from the field, the President and Secretary of Defense did not have a perfect picture of what was going on in Vietnam, but nonetheless delved into the minutiae of the bombing campaign.

The Gun Line

Thanks to the inherent mobility of the naval force and again, our unparalleled logistical infrastructure and proficiency, the Seventh Fleet was able to operate successfully and continually off the coast of North Vietnam. For years, the "Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club", as it became known, was virtually untouchable, both at sea and in the air. With airfields on land under attack, new jet-capable airstrips were still under construction in South Vietnam, meaning that the aircraft carriers were indispensable.

Along the coast of North and South Vietnam, the surface Navy played a vital and possibly last ever final salute of massed naval gunfire. A total of 269 U.S. and four Australian destroyers, destroyer escorts, cruisers, and even at one point, the decommissioned WWII era battleship USS New Jersey shelled targets along the North Vietnamese coast in what was known as the "gunline."

Other warships were tasked with monitoring the skies over North Vietnam with new advanced 3D radars and to issue warnings to U.S. aircraft of enemy planes. Naval replenishment ships enabled the fleet to remain off Vietnam night and day, seven days a week throughout the three and a half years of Operation Rolling Thunder and the accompanying naval shore bombardment campaigns.

There were three main surface navy tasks in this era. The first mission was to support and protect the carriers, launching and recovering planes through Operation Rolling Thunder. The second was to support the Army and Marine Corps ashore, offering mobile and far greater firepower than even the heaviest land-based artillery. There’s a good quote from the USS Saint Paul’s cruise book which describes it well, so I’ll just quote from it here:

A gunfire mission begins with a call for fire from a Marine spotter in the mountains coast of the Republic of Vietnam. He spots enemy movement, or a suspected bunker site, and begins a chain reaction which leads to the mighty guns of the SAINT PAUL.

This spotter, whether in a small plane circling overhead, or entrenched on a mountain top, calls a naval gunfire support group nearby. The target is then cleared for fire if there are no friendly troops in the area.

Within seconds after the call for fire comes in, the “Fighting Saint” is ready. Down in the gun turrets, a projectileman strains to load the breach of an 8-inch gun. In Combat the target is plotted and the brains of the ship, the walls of computers in Main Plot, set guns at the precise bearing and range of the target.

Then comes the order- “Fire” Boom…Boom…

The Saint Paul was unique in that she was the U.S. Navy's last surviving all-gun heavy cruiser and fired the last salvo of the Korean War just one minute before the armistice went into effect at 2159 on July 27, 1953.

But the vast majority of the gunfire ships and sailors involved in the gunline were aboard destroyers, typically armed with three, five, and six-inch guns.

The third major mission was interdiction, either in support of Operation Market Time off the coast of South Vietnam or Operation Sea Dragon, which was launched in 1966 to expand the scope of Operation Market Time's interdiction efforts to the coast of North Vietnam to intercept enemy craft closer to the source.

This new operation came with a significant added danger of being within range of the North Vietnamese coastal defenses, which succeeded in hitting and severely damaging several ships throughout the war while raiding the North Vietnamese coastline. 68 Sea Dragon ships were fired upon in 169 separate incidents. Of the 68 warships fired upon, 29 were hit, causing 19 to withdraw from the area of operations for repairs, although fortunately none of the ships were sunk.

The first two destroyers to initiate Operation Sea Dragon were the Mansfield and Hanson. The two destroyers closed within seven miles of the North Vietnamese coastline before they were fired on by the coastal artillery. Mansfield's rear gun mount engaged the shore defenses with counter-battery fire and escaped undamaged.

On a Sea Dragon patrol, a third of the crew was typically kept at battle stations to be ready for immediate action. Radar men in CIC kept constant watch for surface contacts and coordinated reports with the surveillance aircraft and ships in the area. As soon as either a North Vietnamese logistics vessel or coastal target was identified, the captain would set general quarters and call the entire crew to battle stations.

Sea Dragon operations typically evolved into a dash by the destroyer at full speed forward, followed by a parallel ride along the North Vietnamese coastline, with all three gun mounts blasting away at pre-planned sites and targets of opportunity. The ship's gunfire officer, sometimes aided by a spotter aircraft, walked fire onto the target before retreating out to sea again under the cover of a smoke screen.

The first three months of Sea Dragon operations racked up an impressive 382 enemy supply craft destroyed, another 325 damaged, as well as a slew of shore defenses and coastal radar sites destroyed. These years of gunline firing were so intense, with ships regularly pouring round after round into the Vietnamese coast until the barrels glowed red, the rifling was worn away, and the exterior paint blistered. The ships were then returned to Subic Bay in the Philippines for a quick refit before returning to the merciless gunline.

USS Hobart's 1967 deployment was typical in that over the course of the year, she fired more than 10,000 rounds at more than a thousand targets and was fired on more than ten times in return. Although in her case, she luckily suffered no damage from enemy fire, although she would be hit by three missiles from a very friendly U.S. Air Force F-4 Phantom fighter during her 1968 deployment and return to the gunline.

On the last day of December 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara announced that 864,000 tons of American bombs had been dropped on Vietnam during Operation Rolling Thunder in just two years. This was an extraordinary number, especially when compared to the 635,000 tons dropped during the entire Korean War and the 503,000 tons in the Pacific Theater during WWII.

The public turns (further) against the war

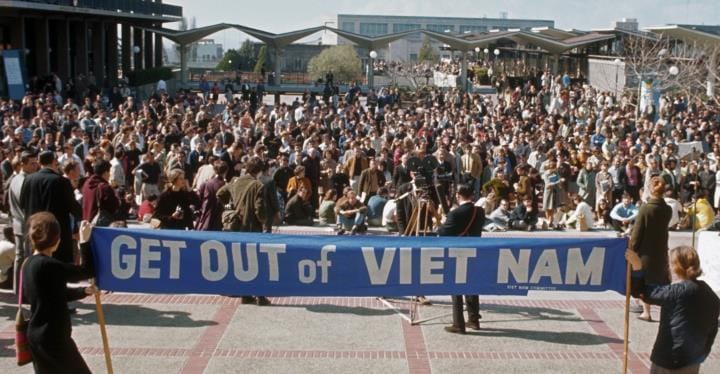

By the end of 1968, the American public was sick and tired of the Vietnam War. The Tet Offensive, which we'll talk a lot more about in the next episode, was routed in part due to the gunline. It was a tactical American victory, but a strategic loss as the American public turned further against the war. By 1968, the North Vietnamese and American negotiators were concluding peace talks in Paris.

By the time Richard Nixon ascended to the presidency in 1969, the war was inspiring mass protests in cities across the country. Contrary to at least my impression of Nixon before really getting into the history of the era, Nixon campaigned on anti-Vietnam War sentiments, promising to bring the boys back home. But of course, it's really easy to make the popular choice on the campaign trail. But when you get into the White House and the generals, the admirals and your intelligence briefers, the Vietnamese and allied governments, they're all telling you that you have to stay fighting, or insert disastrous outcome here will occur. And you know that the buck really does stop with you. And if the disastrous outcome does occur on your watch, you'll, of course, get the blame. And in that case, it becomes a lot harder to keep those pesky campaign promises.

And so Nixon did not want to suddenly pull out of Vietnam and serve up South Vietnam on a silver platter to the army of North Vietnam. Instead he expanded the previous policies of Vietnamization of the war, that is progressively diminishing the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, while at the same time expanding, equipping and training the South Vietnamese forces to take ever more active roles in the war. Feel free, of course, to draw any parallels to our recent history in Asia and the result. If you feel so inclined and you know that the outcome is depressingly similar in many ways.

Back in the South China Sea in June of 1969, the destroyer Frank E. Evans was ordered to leave the Vietnam combat area to participate in a Southeast Asia Treaty Organization exercise in the South China Sea, after which she was going to return to the Vietnamese area of operations. At 0300 on June 3, 1969, due to an error by the bridge watch, the Frank E. Evans cut just in front of the Australian aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne. By the time both ships realized that they were on a collision course, it was too late and the Melbourne ended up slicing the destroyer in two.