I recorded this one in my closet.

This post picks up after concluding the Quasi-War against France and finally achieving a satisfactory, tribute-free peace from the Bashaw of Tripoli after five long and expensive years of war against the pirate state. During this time the United States had also completed the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the size of the country and removing the border friction with France. But the Napoleonic Wars continued to rage on the sea. After fighting the Quasi-War with France over the rights of American sailors and merchants at sea, we were now facing the same issues with the British. In this post I am going to trace events leading up to and the War of 1812, sometimes referred to as the Second War of Independence, against the Royal Navy which was in its wartime 1,000-ship prime.

The Road to War

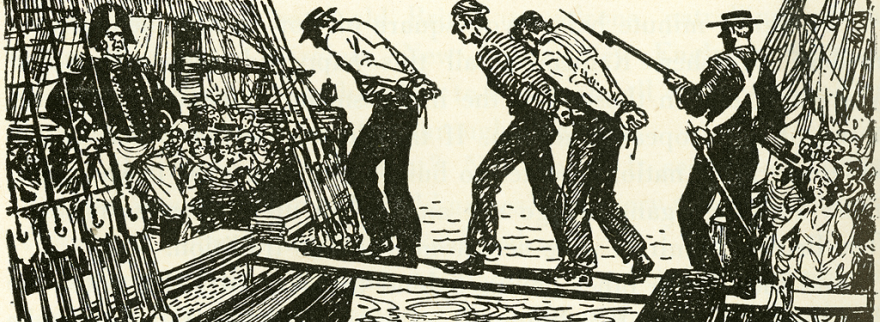

The emotional cause of the War of 1812 was the issue of impressment. Impressment was the practice of abducting American seamen for service into the Royal Navy which was hurting for sailors due to the Napoleonic War manpower shortage. Royal Navy warships were boarding American merchants, often within sight of the Eastern seaboard looking for deserters and evidence that American ships were trading with Britain’s mortal enemy, France. The Royal Navy underwent a fourteen-fold expansion during the Napoleonic era which created a huge demand for manpower which Britain could just not natively supply while also supporting an army to assist their Continental allies. On the waterfront in England “press gangs” prowled and indiscriminately seized able-bodied men in a form of on-the-spot draft.

For their part, the British accused American merchant captains of enticing the more poorly paid and usually unwillingly drafted sailors from their warships into the American merchant service which was expanding rapidly and badly needed sailors of their own to man the growing trade fleet. On the high seas when British warships overtook and boarded American merchants, Britain used the excuse that all the impressed sailors were Royal Navy deserters or subjects of the King, but the truth was that while some were, British captains under orders from their Admiralty were not picky when hauling off any English-speaking sailor from American ships to fill their depleted crews, since distinguishing between a seaman born in Britain and one born in the United States was practically impossible. Here I want to just quote a passage from Ian Toll’s great and classic book on the first decades of our naval history, Six Frigates:

“One pressed into the Royal Navy, an American seaman was immediately confronted with a Hobson’s Choice. He could “enter the books”- that is, enlist formally- in which case he would be eligible to receive wages. In doing so, however, he renounced any right of appeal for his release through official channels. If he refused to enter the books, he would still be forced to serve as any other member of the crew, while receiving no pay. If he refused obey orders, he would be flogged half to death. If injured or disabled in the line of duty, he would simply be landed at the nearest shore, ineligible to receive a pension or medical care at a naval hospital. His officers might confiscate and destroy his protection certificate and take measures prevent him from contacting American government officials to petition for his release. Even when a protest was lodged though diplomatic channels, it could be rejected by the [British] Admiralty on any number of flimsy pretexts. If an appeal led to a discharge order the commanding officer might shelve it indefinitely, on grounds of necessity. In either case, the appeals process could be expected to drag on for years.

By the system’s perverse logic, a pressed American seaman was transformed into a subject of the British crown. He could be compelled to fight and die in England’s wars. After the outbreak of war between Britain and American in 1812 he could be compelled to fight and kill his own countrymen. If he managed to escape, he was forever labeled a deserter, and would be hunted for the rest of his life on land and sea. If he subsequently served in the U.S. Navy during the War of 1812 and was taken prisoner, he could be condemned as a traitor and executed.

Life for an impressed American sailor was bad. But even for the truly British sailor, facing a life of poor pay, poor treatment and an open-ended “obligation” it seems despite the risks, by the estimate of British Admiral Forester, that “at least” half of all British sailors looking to desert at the first chance they saw…say to an American merchant that offered higher pay, better conditions, and used the same language and and to be in port at the same time 🤷? In the end, Great Britain was in a mortal struggle and Britannia ruled the waves, what could a fourth-rate power like the United States do about it?

In 1805 British policy changed to allow Royal Navy warships far more latitude when seizing American shipping. Hundreds of previously allowed shipping routes were rendered illegal under British maritime law and the participating American ships were seized. Since these seizures provided a huge cash windfall to the seizing crew and captain, the Royal Navy enthusiastically and aggressively went about their new task. On both sides of the Atlantic tensions were running high. Americans were furious about the seizures while in Britain some newspapers were calling for a reconquest of their former colonies, which after all had gained independence only 32 years ago. After Lord Admiral Nelson’s decisive victory at Trafalgar later that year over the combined French and Spanish fleets, there was no longer any doubt that the Royal Navy was utterly supreme and unchallenged at sea. A few stout frigates would not be more than an annoyance to the greatest fleet of the age.

One of my favorite and evergreen maxims of foreign policy was recounted by the Athenian historian Thucydides when describing the demands of Greek superpower Athens toward the neutral Greek island of Melos. Demanding that Melos pay tribute and become an Athenian ally against Sparta during the Peloponnesian War, Athenian leaders explained that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” The maxim certainly applied in this case where despite the seizure of nearly 500 American ships over the next two years, Congress recognized that with the pitifully small standing army and navy the United States possessed, there was nothing the United States could do but grin and bear the violations of our neutrality.

Jefferson’s Republicans in Congress did not allocate money for a larger military, other than a pittance to build an ultimately useless fleet of small (and thus cheap) harbor defense gunboats with one cannon each on the bow. These gunboats had the additional political advantage to Jefferson because they could be constructed in any small port which favored his rural base as opposed to just the large port cities where the Federalists dominated. The small gunboats could also theoretically be manned by a “naval militia” which would keep costs for the anti-tax Republicans down and prevent the growth of the military establishment that Jefferson and his Republican feared. That the military adverse Republicans led by Jefferson refused to consider a military buildup was definitely noted by the British.

The Chesapeake Affair

And now with this background, we come to an infamous moment in United States naval history known as “The Chesapeake Affair.” It starts like this: the USS Chesapeake set sail from Hampton Roads on June 22, 1807 for the Mediterranean when they were hailed by the HMS Leopard. Noting the Leopard was behaving oddly but not concerned, the Chesapeake received a Royal Navy Lieutenant via jolly boat who read the Chesapeake a shocking message which amounted to the intent of the captain of the Leopard to muster the crew of the Chesapeake and search her for deserters like she would the crew of any merchantman. This was just not done and would be an act of war.

When the Captain of the USS Chesapeake rightly refused to allow his sovereign vessel to be searched, an aborted attempt was made to bring the ship ready for action, but it was a hopeless task. The gun decks were cluttered, the cannon unloaded, and ammunition was not at the ready. Confusion reigned as the Chesapeake scrambled to prepare to fight- for it certainly looked the Leopard was ready to do so with her guns run out. Finally, after a warning shot was ignored, the HMS Leopard unleashed a full broadside from close range into the Chesapeake.