Read the rest of the series: Part One | Part Two | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six | Part 7

Welcome back to the US Naval History Podcast. We pick up this story as the Massachusetts militia and largest fleet of American ships assembled during the Revolutionary War have just stuck into Penobscot Bay where the British under General McLean are building a fort. The American goal is to destroy this fort before the British can finish their fort and become entrenched.

Early in the morning of July 24, 1779 the Americans have arrived. As the fog clears General McLean began to receive word that the Americas were in Penobscot Bay, but the slowly moving fleet was not yet in sight of his quarter-finished fort. But quarter-finished or now, it seems that time was up and General McLean going to have to go into battle with what he had. And from here, I want to make a somewhat weird proposal, but the next few days of the initial assault can be thought of almost in board game terms. This is not a modern battle with fast communications, no shock and awe, and reinforcements flying in from over the horizon. Both sides don't have any reinforcements coming in the near terms and have to fight it out with what they have on the scene. Decisions get made at commanders conferences, which mean that as soon as one side makes a tactical move, all of the opposite side's commanders walk or in the case of the navy row small boats to a central location, discuss how to best respond, walk/row back to their respective units, and give orders. Their units then very slowly, because again we are in the age of walking, rowing and sailing, make a counter move. The enemy then responds to the response, and the cycle goes on, each side trying to position themselves in a way that will force the enemy to realize they have been outmaneuvered and retreat, or even better outmaneuver the enemy without the enemy realizing it which would allow the enemy to be defeated from a disadvantageous position in a pitched battle.

And the first "American turn" so to speak, was spent gathering some local intelligence. Officers were set ashore and basically started knocking on doors in the area looking for patriotic revolutionaries in the area who could give them an idea of what was going on with that British fort. Despite the delays in getting the expedition underway, this intelligence gathering revealed that the British fort was still in the early stages of construction. This meant taking it would be much easier. General Lovell, who commanded the ground forces for the Americans, was also approached by the Penobscot Indians who offered their assistance against the British, which Lovell accepted. Finally, in the afternoon of the 24th, the American fleet arrived withing sight of the British fort where they anchored for the night. The British for their part recalled the sailors ashore working to construct the fort back to their ships to prepare for a possible clash the next morning and kept a close watch on the American fleet which resembled a "floating island [where the masts were]... a forest of trees."

At 0700 sharp the next morning, Commodore Saltonstall, the commander of the American fleet, assembled his ships. On the north side of the harbor at the peak of the hill on the Bragaduce Peninsula stood the British fort with the British flag flapping in the wind atop a flagpole. Below were two smaller batteries also being constructed guarding the harbor's mouth, and a third battery to the south on a small island called Banks' Island. Three anchored British sloops with broadsides pointed towards the line of attack sat across the entrance to the Penobscot River.

If you're looking for a map, you can find one one at USnavalhistory.com, where you can also find a lot of extra content related to this podcast. There is a link in the show notes for this episode.

Commander Saltonstall sent a ship to investigate and it came back with a similar report that the British fort was far from complete. The Americans seemed to have the advantage if they struck now. But Commander Saltonstall did not press the immediate attack despite the eagerness of some of his subordinate captains. He was far too experienced for that. The huge tides and strong currents of the Penobscot Bay made navigation tricky and variable with the time of day. The bay's geography blocked most of the wind meaning that ship's oars would often have to be used to slowwwwly move against the current.

Here I'm going to quote from George E Buker's book The Penobscot Expedition because I think it offers a good tactical summary of the problem facing Saltonstall when commanding any assault on the British position.

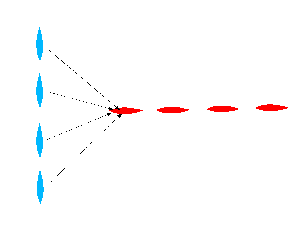

[The British] defensive position employed the ideal offensive formation of crossing the T. [And for anyone who does not know what that is, I have a great illustration on the website post about this, but basically it is a naval warfare tactic used in the age of sail and through the battleship era when one ship was able to cross in front of an opponent's ship at a perpendicular angle forming a "T" shape, allowing the crossing ship to fire a broadside (all your guns on one side of the ship) down the length of the enemy vessel. It allows you to bring all your ship's guns to bear on the enemy, meanwhile, the enemy can only fire their forward guns at you, giving the ship able to fire their broadside a significant firepower advantage. In this case the British ships were anchored and the thus would not have to cross. The American ships to engage would have to very slowly approach against the full firepower of the three British ships while only being able to fire their forward guns.]

Back to George Buker's description:

[The British] has the added benefit of not being underway or depending on the wind and seamanship to keep that position. First Saltonstall would have to wait for a favorable wind and tide. Then, while he could only engage his bow guns, he would have to advance directly in the broadside of all of [the British] ships. If the lead ship became disabled, it endangered his remaining ships in the restricted sea room. Besides [the British] ships, Saltonstall also had the fort on the eminence, two batteries below the fort, and a third on Banks' Island opposing him. Finally, a sudden calm, not uncommon in the area, could place the commodore's vessels in crisis.

Slowly, Commodore Saltonstall's fleet advanced to opposite Bragaduce Island where the British fort lay. They remained just out of gun range. Settling the unarmed transport ships carrying the soldiers safely away from the British, Commodore Saltonstall climbed down from his 32-gun flagship the Warren onto a small schooner to sail around to his warships and issue them instructions. This process took several hours, and now you see what I mean about this resembling a strategy board game of sorts.

Under Commodore Saltonstall's orders, a few American warships were sent out on a probing attack against the British. Five ships made a dash for the British lines, made a quick turn right at the ships mutual cannon range, unloaded broadsides at each other, and then the American column turned out of further British gunshot range. These are the tactics you have to use against an anchored force instead of charging against the top of the "T." There is actually some pretty significant differences in historical accounts of this skirmish in the first day, but everyone agrees that these dash and run cannon exchanges did little damage to either side. However, for Commodore Saltonstall, breaking the British here was never the point. The point was to keep the British busy...