Read the rest of the series: Part One | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six | Part 7

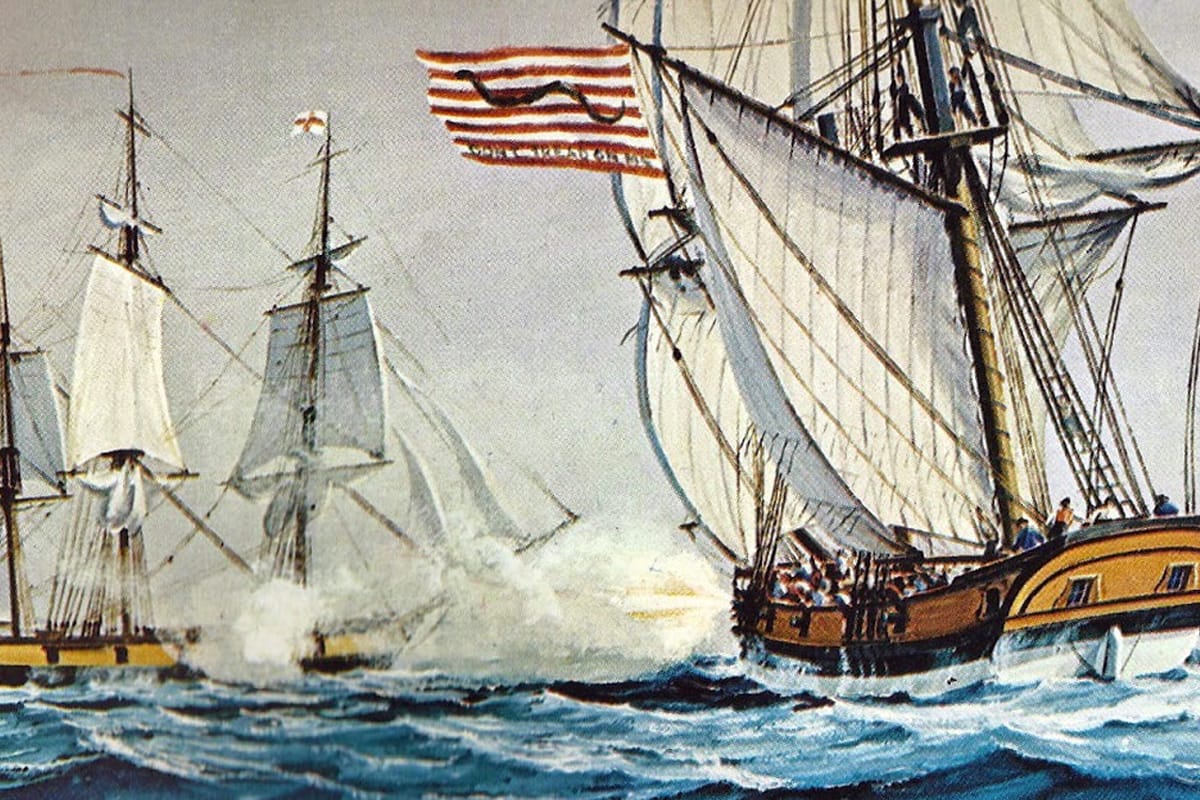

As news of British General McLean's occupation of Bragaduce Island in Maine (then part of Massachusetts colony) reached Boston in late June of 1779, the Massachusetts Board of War quickly decided it was smart of send a combined army-navy force to drive off the British before they could finish building their fort. The Board of War recommended to the Massachusetts legislature gather every available armed ship and vessel and sail in just six days. They also recommended that the government do some combination of compel and pay private armed vessels (aka privateers) to join the expedition.

Now, the general plan of striking before the British could be entrenched is tactically sound, but six days to assemble all of the ships, ships, manpower, and logistics, plus do all of the planning for a large expedition made up of units that have never worked together before? and all without modern communications where coordination happened at the speed of horseback. Six days? Six days?! There is a balance between striking fast and doing the bare minimum amount of planning necessary not to have the expedition turn into an unorganized clusterfuck. With this level of genius strategic planning from the get-go you might begin to understand how this expedition ended up as a complete loss as the American force burned their own ships to avoid capture and thousands of men fled south in a disorganized rout though hundreds of miles of Maine backwoods in the biggest American naval disaster pre-Pearl Harbor.

Obvious flaw ignored, the Massachusetts legislature accepted the Board of War's recommendation of a launch in six days. For this expedition ships were drawn from every available source. The Continental Navy provided three ships including the 32-gun frigate Warren which served as the flagship and biggest source of firepower for the expedition. During the Revolutionary War 11 of the 13 rebelling colonies maintained state navies. Massachusetts devoted all available ships to the expedition, and neighboring New Hampshire kicked in a 22-gun impressed privateer for the assault.

A small aside on privateering

The rest of the force was drawn from the large privateering fleet that had flourished as British trade became fair game. I've talked about privateering a few times in past episodes, but the way it essentially worked was the government gives private citizens the right to attack enemy shipping, subject to certain restrictions. This was distinguished from piracy (at least in the eyes of the people doing the privateering) because privateers could only attack the ships of certain countries their government authorized, abide by some basic rues of civility and not wantonly torture, rape, murder, or sell the crew of captured ships into slavery as pirates were and still are like to do, as well as split the value of the captured ship and cargo with the government which authorized the privateering in the first place. For the most part, privateering was a powerful tool in the Revolutionary War, and later in the the War of 1812 a well. It is a traditional weapon of weaker powers who cannot go toe-to-toe with stronger powers afloat against their stronger rivals. Privateering is a form of guerilla warfare at sea, and just like all forms of guirilla warfare is exponentially harder and more expensive to defend against than carry out. Privateering essentially mustered the entrepreneurial spirit of the rich to finance and arm the seafaring to go plunder the ships of a nation's enemies. This brought in money, badly needed supplies, and just as importantly, cost the enemy a lot of money in the form of lost ships and cargo, which in turn created a powerful lobbying force in the capital of the larger power for ending the war so everyone could go back to making money. The primary downside is that it did divert the finite seagoing resources of ships and sailors away from central, coordinated action and dispersed them to whatever ends the privateers found most profitable.

In the case of Revolutionary America, this tendency to seek out the profitable path rarely meant a toe-to-toe fight with the formidable Royal Navy. So when the call went out for privateers to assemble for an expedition to attack a British fort in Maine, there were very few takers...British forts not being generally known for their looting potential. Despite the state of Massachusetts's offer to pay for all expedition expenses and a fee to essentially rent the privateer's ships, the owners and captains were generally not interested. Tired and desperate with the days ticking by, twelve privateers were eventually involuntarily impressed into service for the two month term that the expedition was expected to take.

Gathering the men and supplies

With the ships secured, the second problem of manpower and supplies presented itself. In those sailing days the civilian sailor and naval sailor needed and possessed similar skill sets and often switched back and forth between ships after a cruise contract was up. Today this is very much not the case. Navy sailors spend most of their working hours operating, training on, and doing maintenance on military equipment which often does not have a close civilian equivalent. But right now, very few sailors wanted to join the expedition. The chance of being compelled to extend service indefinitely with the Continental Navy was not welcome, but the lower wages on offer for military service sailors was an even bigger incentive for the experienced sailor to avoid the roving press gangs looking for able bodied seamen.

Just as pressing as the men, a navy is an incomprehensibly complex organization that eats supplies at a pace with few parallels. Rope, wood, tar, food, gunpowder, cannon, sailcloth, nails and every other war good was in short supply and the state of Massachusetts ended up seizing the required goods and then paying what they considered a market rate for them rather than allow the vital war goods to be subject to a bidding war that was getting feverish with the rapid buildup of ships in Boston Harbor. (Note: this is somewhat similar to the Defense Production Act of 1950 which allows the President to require industry to prioritize DoD orders in certain emergency circumstances.) All of this naval preparation did not, to say the least, come together in six days. In fact, it took more than a month. But as the ships and supplies began to flow to Boston Harbor, the public support and excitement for the expedition grew.

Building a landing force

If the process of assembling a fleet was poorly coordinated, the process of assembling the landing force that in theory would drive British General McLean and his troops off of their fort was somehow even worse. The state of Massachusetts was so confident that their expedition would succeed that they did not bother to tell Continental Army General Horatio Gates in neighboring Rhode Island about the expedition or ask for any Continental Army troops. The Massachusetts leadership deliberately kept George Washington and the Continental Congress in the dark about the pending expedition to Maine because of the belief that "If but ten Continental soldiers are concerned, the Continent will take all the honor."

Instead of launching the Maine expedition with full time soldiers now veterans of fours years of hard warfare, Massachusetts relied on their militia. To be fair, many of these militia men were also veterans by this point, but they were also by definition part-time soldiers. And many of these part time soldiers proved a little reluctant to muster for the expedition. Each town was given a quota of men to fill for the expedition, and when that still did not produce enough volunteers, it became what we in the navy like to call "voluntold." Soldiers were sent out to the towns short on their quotas and they started assembling the landing force by any means necessary. In the words of a Major Hill who lead one enforcement group "Some were taken & brought by force, some were frightened and joined Voluntarily, & some Skulk'd and kept themselves concealed."

Of the soldiers that did join the expedition, it does not seem like any particular village was eager to send their best. The same Major Hill summed up the soldiers sent as "Boys, Old Men, and Invalids, if they belonged to the train Band or Alarm List they were soldiers whether they could carry a Gun, walk a mile without crutches, or only Compos Mentis [sanity] sufficient to keep themselves out of Fire & Water." In other words, instead of Continental Army soldiers, the expedition landing force was being manned with the dregs of the Massachusetts state militia, which even after being forced to volunteer were found by one of the expeditions generals to be "One forth part...Small Boys, & Old Men, & unfit of the service," and despite all of that still short 500 of the planned 1500 man landing force the expedition planned to embark with. Nonetheless, the men were loaded up on the 21 transports waiting in Boston Harbor.

The expedition departs

With the men and ships now assembled, some three weeks after the initial ridiculous six day deadline, the fleet left Boston Harbor on July 24th, 1779. In command of the naval aspect was the well-regarded Commander Saltonstall of the Continental Navy who lead a force of three Continental Navy ships, three from the Massachusetts state navy, and twelve armed privateers all powered by a combination of sails and oars, which would be vital to any river warfare in the Penobscot Bay. The landing force aspect of the expedition was lead by General Lovell with Col. Paul Revere, yes that Paul Revere, leading the artillery.

But wait, you might have just noticed that I didn't mention who was in overall command of the expedition, just that there was a naval and a land commander. That would be because...there was no overall commander. Yep, as amazing and stupid as that sounds from the perspective of an era soaked in the mantra of joint operations, there was no overall commander. General Lovell could not force Commander Saltonstall do do anything he didn't want to do, and Commander Saltonstall could not force General Lovell to do anything he did not want to do either. There was a total reliance on the cooperation and agreement of the two services to work together on what they mutually agreed was the best course of action. Perhaps, dear listener, given your knowledge of the pending disaster, you can foresee how this is going to be a problem down the road.

But... for that you will have to wait for the next episode. For now, the summary that historian George E. Buker whose book on the Penobscot Expedition I am relying on for a lot of the research in this podcast sums the situation up well when he says, "The Penobscot Expedition made an impressive sight. Yet looks were deceiving. The militia lacked a third of its scheduled numbers. The militiamen...came together as a unit the day before departing. The expedition's armed vessels were equally poorly prepared for the task at hand. Finally the two commanders and their staffs failed to arrive at a common strategy at their first meeting. It did not bode well for the expedition."

The next episode will be out in a few days, but until them, I have a new website USnavalhistory.com, and it has an option to donate. I want to give a big thanks to my first donor, Nate D. I get a little email notification whenever someone donates. So far I admit I've only had one, but when that notification came in I was very relieved because I had no idea if anyone at all liked the podcast enough to donate. So thanks again Nate, and if anyone else wants to donate, the link in in the podcast show description, as well as on the website USNavalHistory.com. You can also sign up for the 100% free newsletter there, comment on the posts which accompany each podcast episode, and of course send me an email at usnavalhistory@gmail.com.

Until next time, Fair Winds and Following Seas!

Member discussion: