This week we are going to cover everything from the end of the Civil War through when the United States beats Spain in the Spanish American War and emerges onto the world stage as a great power, with colonies and a navy to match our newfound status. We are also going to touch on some of the changes the navy went through during this period and leave off around 1900.

Reconstructing a Nation and a Navy

At the end of the Civil War, the Navy was immense: 671 ships and 58,000 officers swelled the ranks. But a navy built for blockading the coastline of an enemy without a real navy and taking rivers was not well suited to war with a major naval power. The nation was preoccupied with Reconstruction. The actual physical rebuilding alongside attempts to rectify the political, social, and economic legacies of slavery on newly freed black Americans which clearly ended about a decade after the Civil War due to back room political dealing. We are still dealing with the legacy of our national failure to protect the rights of and provide opportunity for millions of newly freed slaves.

The other preoccupation was westward expansion. Railroads made it easier to move west. High tariffs protected the domestic market and meant that American businesses were less interested in expanding overseas and thus did not need an aggressive navy to protect and open new markets.

By 1870 the Navy would shrink to 52 warships and 10,500 officers. Like naval retrenchment after Revolutionary War and War of 1812, the navy that did exist returned to its pre-war squadron duty. War plans with a European power envisioned employing Alabama-like commerce raiders to sink enemy shipping and focus on coastal defense.

Undersea telegraph wires also cut the round-trip communication time from Washington to naval commanders on distant stations from more than a year. Wireless communication was not widespread yet but the idea of waiting orders in a port caused Naval officers to grumble that they were being micromanaged by the Navy Department in Washington…an idea that would make the truly micromanaged flag officers of today laugh out loud with their daily VTC calls, reams of emails, instant messages, and other direction coming from the Pentagon straight to the ship on a daily basis.

Overseas it became increasingly obvious thought that the U.S. Navy was outclassed in every way. Foreign navies were building bigger, more technologically advanced ships every year while we progressed at only a glacial pace past Civil War era monitors. Oscar Wilde made jokes about our navy and foreign ports were an embarrassment when ships of various countries were being compared.

The Virginius Affair

The Virginius Affair in 1873 proved particularly embarrassing. Elite landowners in Cuba were fighting a ten year long rebellion against colonial overlord Spain over issues of taxation, representation, and colonial policy. Inside the United States, there were expansionist factions who advocated supporting the rebelling Cubans against Spain but Grant decided to keep the nation neutral.

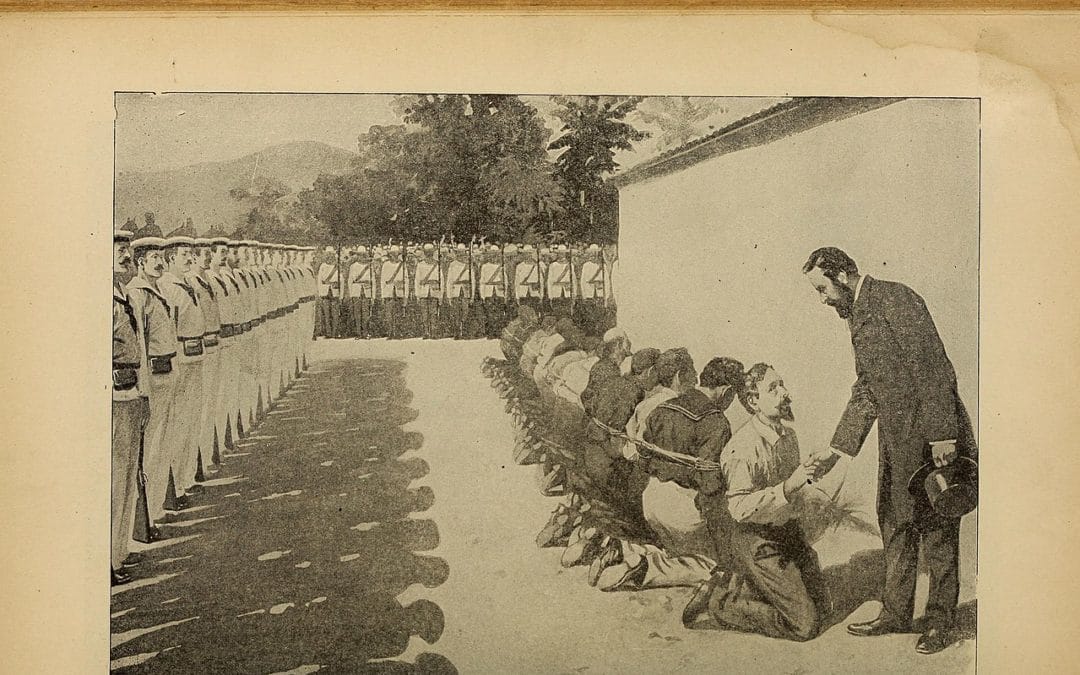

In 1870 private citizens purchased the former Confederate blockade runner and used her to run the Spanish blockade of Cuba bringing volunteers and weapons from the various ports to aid the Cubans for the next three years. The Spanish, however, considered them pirates. In 1873, former Confederate Commodore Joseph Fry was the captain of the Virginius and was captured by the Spanish. Fry and his mostly American and British crew were tried as pirates and sentenced to death. After executing and mutilating a first batch of 53 sailors, including Fry, the executions were stopped when a British warship appeared off the Santiago coastline and threatened to bombard the city unless the executions were stopped.

Even though the Americans executed were very obviously guilty of running the Spanish blockade, the American public reaction to the executions was angry and leading newspapers including the NYT called for war against Spain. While Spain and the United States negotiated reparations regarding the affair, the U.S. Navy was ordered to put on a show of force near Cuba. The navy gathered the fleet off of Key West, Florida for maneuvers and promptly embarrassed itself when several ships broke down.

The resolution was peaceful which was fortunate because in the words of Admiral David Porter: “the fleet showed itself very unsuitable for war purposes, either to contend against the improved class of vessels now being constructed by all foreign powers, or to cut up an enemy’s commerce.”

In the years that followed Congress slowly began to realize the need for a more modern navy. In 1883, Congress approved the ABCD ships if you remember back to episode 4 which were semi-modern ships made of steel with electric lighting and breech loading guns, but still featured sails. European powers had abandoned sail by this point, but United States needed them, because we lacked extensive overseas possessions from which to re-coal.

The nation was slowly acquiring them though. The first was a small, uninhabited island in the middle of the Pacific…called Midway. Slowly, Congress authorized more funds and the American industrial base built itself up to the task of building modern battleships. 1890 was the turning point. The Western frontier “closed causing the country to look overseas for further expansion. In addition, the navy was finally building a steady supply of large battleships that befitted a nation which was a world power in every respect except militarily since the United States still felt secure from the threat of serious invasion. The Indiana class battleship funded was the first capable of long-range steaming and seriously contesting with foreign navies. Gradually, the Navy became a national symbol of pride.

At the same time, the U.S. Navy found itself on the cutting edge of theories of naval warfare. American naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan published what became one of the most influential books of all time: The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660-1783. In it, Mahan provided an analysis of how the small island country of Great Britain became the most powerful nation in the world and acquired command of a global empire on which the sun never set. He theorized that it was all achieved on the back of the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy possessed a fleet of capital ships which drove their enemies from the sea and allowed them to control trade, which allowed them to get rich, which in turn allowed them to pour more money into their powerful fleet, locking down overseas trade in a sort of self-perpetuating flywheel.

Mahan’s book focused on the United Kingdom, but the implication was that the United States could, and should, follow the same strategy to emerge as one of the leading global powers. This lesson of concentrated fleets of capital ships as the lynchpin of national power was one that caught on in Japan and Germany as well. These ideas contributed to a naval arms race leading up to World War I in Europe that we’ll delve deeply into in the next episode and spurred Congress in the 1890s to massively increase naval investment.

Mahanian strategy also called for a Central American canal which would easily link the Atlantic and Pacific coastlines, and an extensive collection of overseas territories to serve as coaling stations. In the event of war, the Navy would need to be able to defend American possessions away from the homeland in a form of offensive defense.

With the growing naval might, the United States began to use it to assertively intervene in foreign affairs. The nation would engage in a contest for the Samoan Islands with Great Britain and Germany while also competing with the British for the Hawaiian Islands. The United States exercised an assertive foreign policy in Latin America and in defense of the Monroe Doctrine when European powers attempted to mettle in the Western Hemisphere.

Making a New Navy

The New Navy was a more technical affair than the old navy of wooden sailing ships and required a new type of sailor. Throughout this period, the one bright spot of Naval Development was the continued professionalism and training of both the officer and enlisted corps. On the officer side, the U.S. Naval Institute, Naval War College, and Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) were all established in this era. Particularly, the Naval War College was meant to, in part, teach Naval Officers about the broader art of war and build on the lessons learned conducting Combined Operations during the Civil War. Notably, the Officer line and engineering corps merged in 1899, but advancement progress was slow without an up-or-out system to retire old officers who would cling on to their positions until old age or even death.

Reforms were not limited to just the officer corps but affected enlisted sailors as well. The old way was to recruit civilian sailors and immediately send them aboard a warship where they learned of the relatively few differences between civilian and military sailing life on the fly, for example how to load a cannon, etc. Problems with this model were high turnover, and a multinational force which officers referred to as the “dregs of all countries.” This led to questions of loyalty during a potential war and communication was hard since many languages would be spoken onboard. The Navy that was going to be a national symbol needed American crews.

After the Civil War, an apprentice system where young men were “apprenticed” aboard warships and known as “boys” served until 1880. Then a more formalized training system was implemented. First, land based naval school developed which was a moored ship where new recruits learned the basics of ship life. But with the expanding navy of the 1890s and more technical demands, new skills were needed. Thus, the Navy started recruiting from the inland population without a nautical background. Recruiters spread the word throughout the country: think classic recruiting posters with an emphasis on adventure and travel that exhorted young landlubbers to "Join the Navy, See the World."

Land based classroom training was also developed at major naval bases during the period. Today, the Navy runs hundreds if not thousands of schools around the country which teach just about every conceivable skill: from basic engine maintenance to photojournalism to complex battle tactics as the skill set required has expanded.

The darker side of these reforms was a segregation of the enlisted force. Prior to inland recruiting of mostly white recruits, the force had been multiracial with all races filling all enlisted roles on the ship and living in an integrated manner. The new, whiter force marginalized black sailors' opportunities and even stopped enlisting black sailors completely between 1919 and 1932.

Spanish-American War

The test for America’s new navy came right at the end of the 19th century. In 1896, the Navy commissioned the world-leading Indiana-class battleships and with that announced the United States as a military force to be respected again. When she was commissioned, the Indiana was briefly the most heavily armed battleship in the world and clearly designed to engage and destroy the main enemy fleet, not protect the coastline or conduct commerce raiding. To maximize the impact of these new battleships coordinated fleet tactics were needed, and I can tell you from personal experience that this is something that takes a ton of practice to do well. The consequences of not doing it well are collisions, as the British demonstrated when the HMS Camperdown sank the flagship of their own Mediterranean Fleet the HMS Victoria in 1893 during fleet maneuvers.

Since these new massive battleships were vulnerable to below the waterline attacks, naval rams were en-vogue before being eclipsed by self-propelled torpedoes. To chase off small, inexpensive torpedo boats, navies developed a class of small, fast ships with small caliber, quick-firing guns called torpedo boat destroyers which was eventually shortened to a designation we know today as “destroyers.”

A middle class of ships were known as cruisers which varied from heavy destroyers to light battleships and generally were tasked with eliminating the enemy destroyers in a game of naval rock, paper, scissors but were vulnerable to enemy battleships in turn.

The Sinking of the USS Maine

With this mix of ships, the United States Navy found itself thrust into a new role. Around the world the last remnants of what had once been the sprawling Spanish empire was disintegrating. Cuba was fighting another war for independence and the Philippines were also engaged in a revolution against their Spanish colonial overlords. Close to American shores, the bloody and atrocity filled Cuban revolution was red meat for the yellow journalism of the time which was less concerned about the truth of a story than gruesome photos and headlines which would sell papers. The public lapped up the tales of blood, torture and war and the public soon began to again agitate for helping the Cuban people throw off the yoke of Spanish oppression.

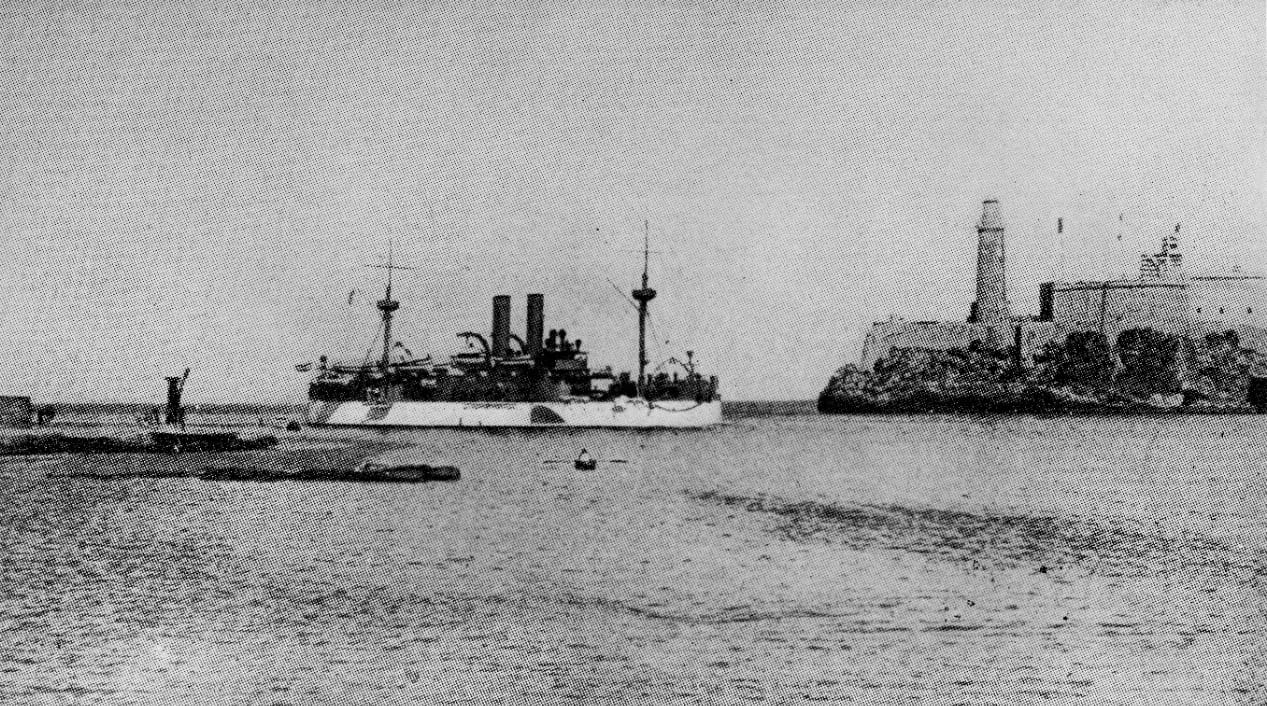

In February of 1898, the USS Maine was sent to Havana, the capital of Cuba, to monitor the situation and put pressure on the Spanish to protect American lives and commercial interests, when late one evening a huge explosion ripped the Maine apart, sinking her and killing most of her crew. The yellow press seized on the explosion, blamed the Spanish without much evidence, and called more loudly than ever for war, of course knowing that war sells more papers than anything else. As a historical side note, it was probably a spontaneous coal fire which set off an internal ammunition magazine which destroyed the Maine. The Spanish Prime Minister knew of the rising war tide in the United States but was trapped by the political considerations at home. The Spanish public saw Cuba as an integral part of Spain and to give Cuba up would have been political suicide and so the Spanish Prime Minister could not offer full independence to a colony that was increasingly an endless money pit of rebellion anyway. At home, even though President William McKinley did not want to go to war with Spain, and the Spanish Prime Minister did not think he could win a war against the United States, after an initial navy investigation concluded that a mine had probably sunk the Maine, the public was frothing at the mouth for war and he saw no political choice. On April 25, 1898, Congress declared war on Spain.

Now, at the time, a young Theodore Roosevelt was serving as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. His boss, the actual Secretary of the Navy, took a day off leaving Roosevelt in charge. Roosevelt took advantage of his conservative bosses’ absence and dashed off a bunch of orders to navy commanders putting them on a war footing. To Commodore George Dewey, who as a young LT had run Forts St. Philip and Jackson as part of Farragut’s capture of New Orleans but since then had led an unremarkable career, Roosevelt sent an order to: “Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war Spain, it will be your duty to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave Asiatic coast and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands.”