This post discusses the Mexican American War before circling back to discuss a couple of piracy smack-downs, trade, and the game-changing naval revolution that the steam engines proved to be during this period. Before we get started with the Navy stuff, I am going to set the stage with a very quick summary of the Mexican and Texan history which ultimately pulled the United States into war with Mexico, setting the stage for America’s second huge territorial expansion and deepening the divides which would rend the nation apart during the Civil War 20 years later.

Mexican Independence

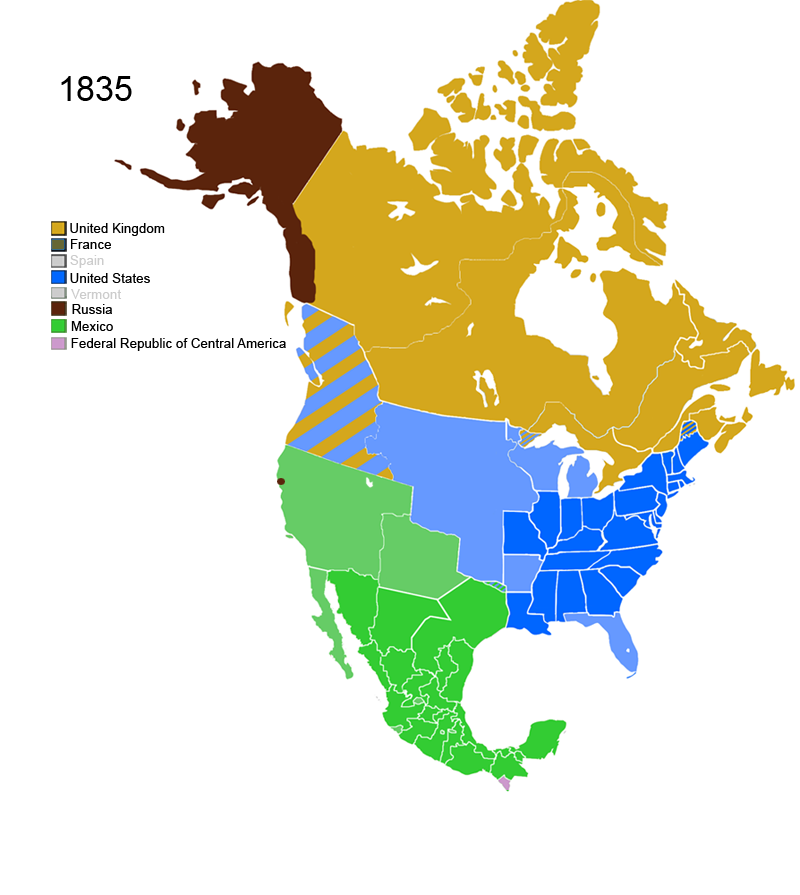

One of the proximate causes for Mexican independence was the French conquest of Spain under Napoleon and the eventual replacement of the Bourbon dynasty in Spain with Napoleon’s brother, Joseph Bonaparte as king of Spain in 1808. After thirteen years of their own revolutionary war (our Revolutionary War "only" lasted eight of which the last two featured no major fighting) Mexico gained effective independence, but would continue fighting Spanish forces sporadically until 1836 when Spain finally recognized Mexican independence. In many ways the Mexican revolution was similar to our American revolution: it featured ragtag armies of farmers who fought a long war of attrition against a European colonial overlord. When Mexico was granted its freedom, it named itself the United States of Mexico and had more territory than the United States, even after we doubled the size of our country through the Louisiana Purchase.

But the Mexican struggle for independence was not as united an endeavor as the 13 British colonies had been and the new Mexican nation proved to be even less cohesive than even the fractious early days of the United States of America. From the outset several men claimed the presidency after Mexico’s inaugural election. A general named Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna eventually seized effective control of the Presidency but was forced to spend the next several years personally marching the army back and forth across the country putting down rebels who did not accept his rule.

One of Mexico’s northern states, Texas, abutted the newly expanded United States and American settlers moving west soon outnumbered Mexicans in the huge, sparsely populated territory. Mexico’s continuing political turmoil further prompted the Texans to agitate for independence from Mexico, with the ultimate goal of unification with the United States. In 1836, expecting but not ultimately receiving official aid from the United States, Texas declared independence from Mexico. General Santa Anna marched his professional army north to Texas, defeating the Texans at Goliad and at the famous battle of the Alamo before the Texans eventually regrouped and resoundingly defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. Santa Anna was deposed as Mexico’s President, Texas was now effectively independent and Sam Houston was elected as Texas’ first President. Ten years later Sam Houston convinced the United States of America to accept Texas as our 28th state.

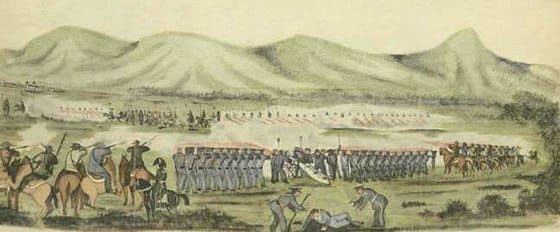

A (highly) fictionalized account of Santa Anna's victory at the Alamo and execution of Davie Crockett.

Texan Independence

This Texan acquisition bought the United States into an existing border dispute between Texas and Mexico. President Polk sent the US Army into the disputed territory and Mexican and American troops were soon skirmishing throughout the border region. Polk used these skirmishes to call for a declaration of war with Mexico and in a contentious vote with former President John Quincy Adams and future President Abraham Lincoln dissenting; Congress declared war against Mexico.

The Mexican-American War

The Mexican-American War was primarily fought by the Army which included future Presidents Zachary Taylor and Ulysses S. Grant, as well as future Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The Mexican army was led by General Santa Anna who returned from his exile in Cuba and declared himself President for the 11th (!) time.

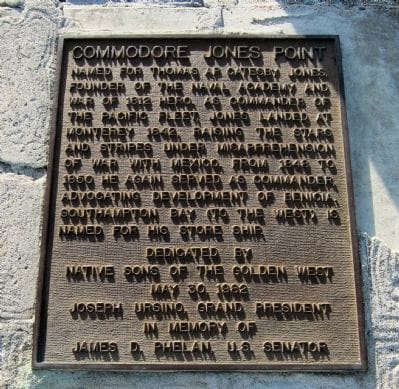

The Navy’s role in the war occurred in two theaters. The first was off the California coast where the navy had actually accidentally started operations four years earlier. In 1842 the then-commander of the Navy’s Pacific squadron, Commodore Jones, received word that war had broken out between the United States and Mexico while in port in Lima, Peru. Furthermore, the rumor was that a secret treaty was invoked for the deeply indebted Mexican state to sell California to the British for $7 million. Lacking a telegraph to confirm these rumors, Commodore Jones, invoking the Monroe Doctrine, set sail for California. On October 19th Jones’ squadron arrived off the coast of Monterey, the capital of California. Jones sent his second in command ashore to demand the surrender of California by 9am the next day from the confused Mexican authorities. The next morning, not receiving the expected surrender from a country he was not actually at war with, 100 sailors and 50 Marines landed at the port and took the practically undefended city without resistance. The next day Commodore Jones went ashore and discovered that war had in fact not broken out and that California had not in fact been sold to the British, apologized, had the American flag which had been flying above the city taken down and replaced with the original and rightful Mexican flag. Leaving the port with a salute to the Mexican flag, Commodore Jones was relieved of command shortly thereafter.

When war actually did break out four years later on May 12th, 1846, the new Commodore of the Pacific Fleet had orders to seize California and just as importantly make sure the British did not seize California as repayment for the debts the Mexican government owed them. Commodore John Sloat arrived in Monterey two weeks before the British and bloodlessly captured the city for the second time. While Sloat’s sailors began building a fort to defend the city, other American landing parties quickly captured San Francisco, Yerba Buena, Santa Barbara, San Diego and Los Angeles. The Mexican army in California proved to be poorly supplied, undermanned, and in the words of Navy Chaplain Walter Colton had “as little discipline, sobriety, and order as would characterize a bear hunt.” Less than six weeks after landing at Monterey and three months after the war had started Mexican forces in California surrendered.

Despite the surrender of Mexican forces in California, this did not end the fighting in the Pacific theater. As the fleet sailed south along the Mexican Pacific coastline capturing towns, merchant ships, and forts in Baja California, Mexican resistance led by Mexican Army Captain José María Flores drove the American garrison out of Los Angeles and the garrison in San Diego was besieged until they were found starving and surrounded by the USS Congress who relieved them. By November Mexican forces had wrested control of all of the territory south of San Francisco except for San Diego and Monterey.

In 1847 the tide began to turn again in the United States’ favor. A Marine detachment under the command of Captain Marston defeated the Mexicans at Santa Clara and after suffering a string of defeats against a combined force of army and Marine troops, the now-General Flores fled to Mexico leaving his second in command, Major Pico to surrender and in the Treaty of Cahuenga granted America the territory of California. The navy continued landings and raiding Mexican shipping off the coast of Baja California throughout 1847 as well as defending American shipping from Mexican privateers (who we of course called pirates). By the time the war ended in 1848 American flags flew over most of Baja California’s significant ports and cities.

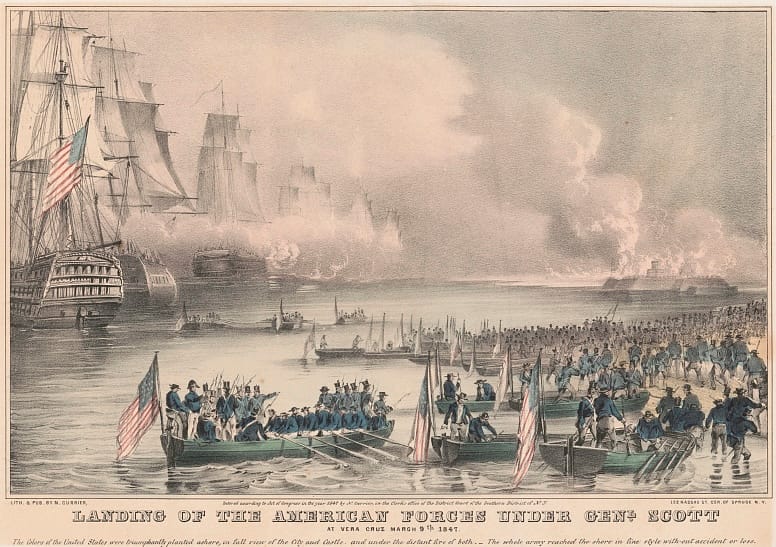

Meanwhile in the Gulf of Mexico an American squadron under Commodore David Conner faced little resistance as they blockaded the Mexican coast. At the beginning of the war Mexico possessed only two warships and promptly sold them to Britain knowing they would not be able to stand against the much larger United States Navy. In the north General and future President Zachary Taylor engaged Santa Anna in a series of bloody battles but faced with the prospect of a thousand plus mile march south across the Mexican desert, President Polk decided to bypass the bloody march and approved of an amphibious landing at Veracruz. Under General Winfield Scott, Commodore Conner’s second in command Captain Matthew Perry planned the largest amphibious landing in world history, a record that would hold until the disaster at Gallipoli in WWI.