Welcome to the Most Dangerous Moment in World History (dun dun dun duhhhh)

We're now in the midst of the Cold War, and this post will cover probably the closest we as a human species ever came to nuclear Armageddon.

The thing about the Cuban missile crisis is that the more you learn about it, the more you realize how disgustingly close we were as a civilization to nuclear annihilation. Historians (and podcast hosts) today have the benefit of secret tapes and archival documents which reveal the tense decision making of President Kennedy and his advisers, as well as the secret archives of the Soviet Union, which opened up after the end of the Cold War.

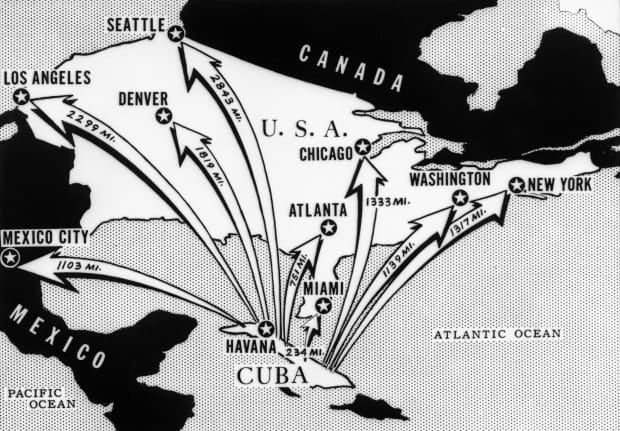

We know that General Maxwell Taylor, Kennedy's chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the highest ranking officer in the United States military, advised Kennedy to launch massive air strikes against Cuba with no advance warning in order to disable the Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba before they had a chance to become operational and a threat to the U.S. homeland. We also now know that some of these nuclear missiles were, in fact, already operational and ready to launch on short notice.

The Air Force chief of staff, General Curtis LeMay, told Kennedy, "We don't have any choice other than direct military action." Of course, with 20/20 hindsight, we did have a choice. Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who advised Kennedy, told him that he supported the military's decision to launch an assault.

Had a different choice been made then by President Kennedy, you would probably not be listening to this podcast here today. There probably would not be any podcasts at all. There might not be many humans left. The 13 days in October 1962 of the Cuban Missile Crisis were probably the most dangerous days in recorded human history. This is that story.

In the immediate years after the Korean War ended in an armistice in 1953, President Eisenhower continued the grand American tradition of dramatic military budget cuts. His new theory of national defense rested on brinkmanship, paired with a "cost-effective" policy of massive retaliation if the Soviet Union got out of line. Truman's Cold War strategy of containment, a more measured response to communist aggression, went out the window.

The new policy advocated for by Secretary of State John Dulles was to launch a massive empire-destroying retaliatory strike against the USSR for any communist offensive war anywhere in the world, regardless of whether the Soviets were directly involved or not, therefore making the USSR keep a tight rein on all the smaller communist powers around the world. If there's a little bit of ambiguity about where that line was, that would trigger a nuclear onslaught, so much the better. A little fear never hurt anyone, or so the theory went.

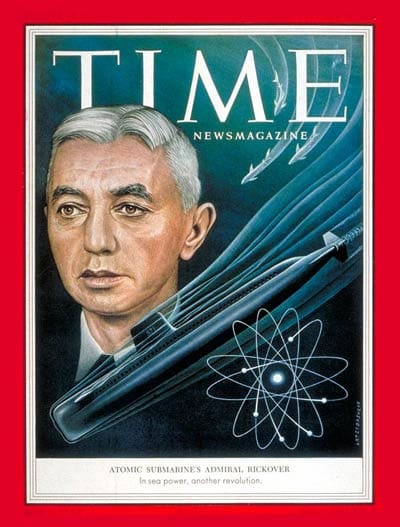

Army and Navy budgets got slashed to pay for the Air Force's nuclear delivery programs. The Navy was a pretty easy target because the Soviet Union was focused on coastal defense at the time, but the Navy was saved from total devastation by taking part in the newly prominent nuclear mission. Billions and billions of dollars were poured into research and development of nuclear propulsion and ballistic missiles under the purview of Admiral Hyman Rickover.

Rickover was a character, and I hope to get to a whole post on him at some point. But for now, it's enough to know that he single-handedly ruled over the Navy's nuclear program for two decades. And having gone through the Navy's nuclear program, I can say that the nuclear program still has what is probably an unhealthy obsession with his legacy and various eccentricities. But that's a story for another post :)

Under Rickover's leadership, the Navy launched its first nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus. Nuclear power allows submarines to stay submerged indefinitely, stay out to sea longer, go faster and crucially, be large enough to carry ballistic missiles. For that, the Polaris missile was deployed with a capable range of over 1,200 miles. The Navy was now officially the most important part of the nuclear triad.

The Nuclear Triad

The nuclear triad is composed of the three methods of delivering nuclear weapons on the enemy:

- The first and simplest method is by bomber- literally just going and dropping a nuclear bomb on the enemy, World War Two style.

- Intercontinental ballistic missiles launched from a cornfield in, say, North Dakota or central Kazakhstan were a lot harde r to shoot down than a bomber, and had the added benefit of not putting airmen in direct danger.

- and finally, the "best" (most survivable) method of nuclear weapon delivery: by submarine. The submarine component is by far the most important because submarines are easily hidden and are mobile under the oceans of the world. It's much easier to locate fixed missile silos, and you can much more easily attempt to shoot down all the enemy bombers before they reach your major cities. But as long as the enemy, in this case the USSR, could not be 100% certain that they could preemptively find and destroy every. single. one. of our nuclear submarines before launching a first strike against us, all the leadership in Moscow knew that just one nuclear submarine could launch a retaliatory nuclear strike. And given the devastating destruction of only one nuclear missile, every leader had to have the calculation going on in the back of their mind, "What on God's green earth could possibly be worth the risk of us losing tens or even hundreds of millions of people and probably all of my biggest cities over?" And thus, the balance of power, the Cold War, and ever since has hinged on the concept of mutually assured destruction. You kill me, I kill you. So let's agree not to kill each other. Deal.

But before the theories of mutually assured destruction were fully fleshed out in those early Cold War days when the United States had a pretty decisive nuclear edge, there was a strain of thought in Washington that thought that we, the United States, could win a nuclear exchange if it came down to it. The norm against nuclear weapon use was not as strong in the first two decades of the Cold War. These factors combined to make the world a dangerous place. The closest that Eisenhower ever came to using nuclear weapons was during the Taiwan Strait Crisis when the communist Chinese mainland began shelling the nationalist-controlled Taiwanese outer islands. The nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek seemed prepared to launch an invasion of their own. The crisis spiraled, and the Navy was called on to mass evacuate Taiwanese citizens from the outer Taiwanese islands.

Taiwan Strait Crisis

Eisenhower, in a perfect example of nuclear brinkmanship, threatened the Chinese with nuclear weapons should they invade Taiwan. "There is going to be no bloody repeat of the Korean War under his watch," the Chinese backed off. But not before Soviet Premier Khrushchev threatened a retaliatory nuclear strike should we Americans nuke China. The Chinese decided against escalation, but notched up another lucky win for humanity.

When the young and inexperienced President Kennedy took over from the grizzled war hero and former World War Two Supreme Allied Commander, President Eisenhower, Soviet Premier Khrushchev doubted Kennedy's resolve in the face of potential nuclear war. Kennedy issued a more flexible military response and backed away from Eisenhower's nuclear brinkmanship. All of this led to the greatest crisis of the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Cuban Missile Crisis Begins

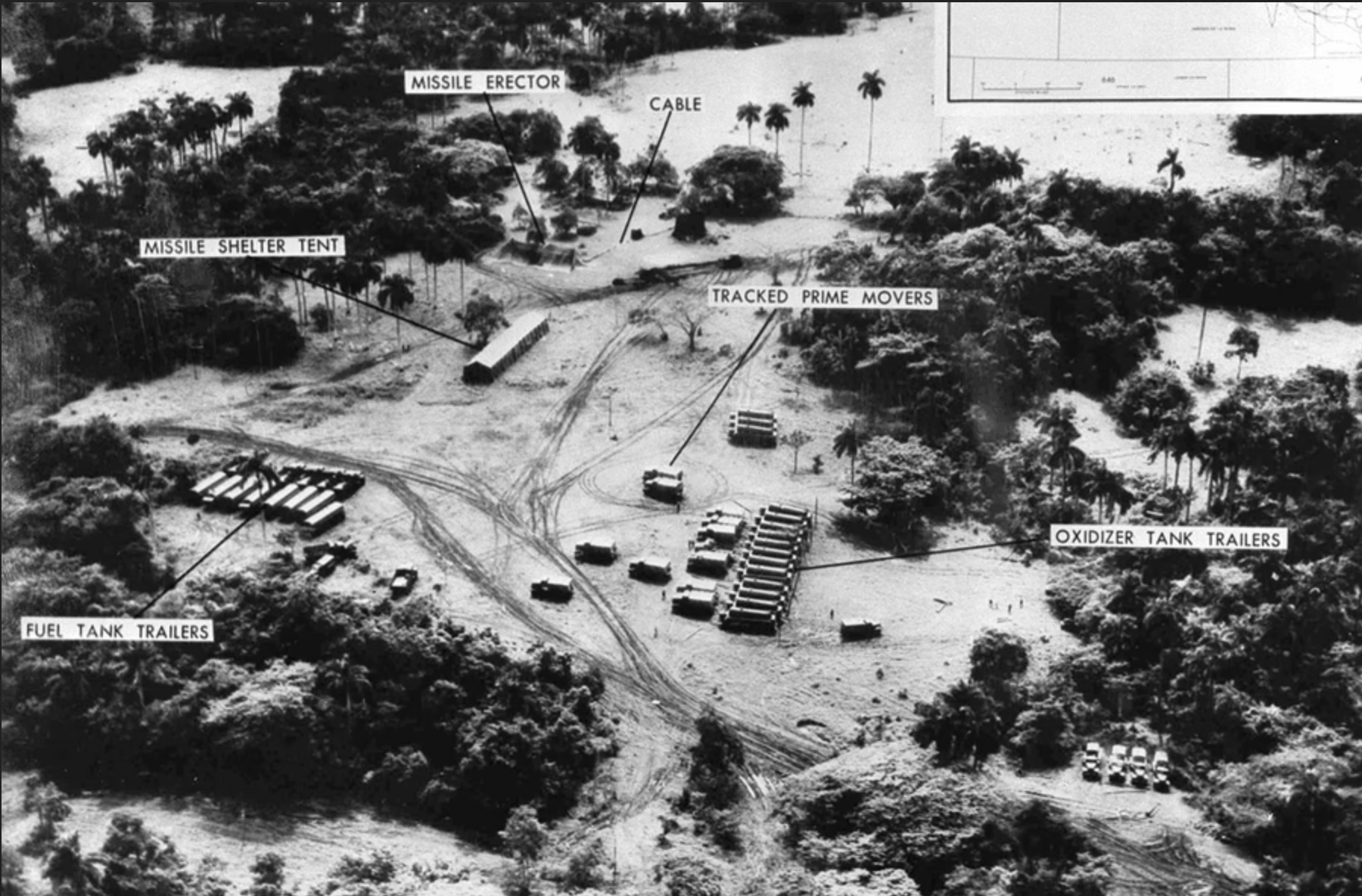

While the U.S. was distracted by the Berlin crisis and our response in the form of the Berlin airlift, Khrushchev launched Operation Anadyr, a secret Soviet operation to transport missiles, bombers, and troops to Cuba to counteract the American missile advantage. A Soviet double agent alerted the CIA of the plan before it could be finished, though, and after it was confirmed by spy plane photography, President Kennedy knew that the Soviets were just weeks away from basing nuclear missiles only 90 miles off the coast of Florida.

Blockading Cuba

Soviet tankers were inbound with more parts, and Soviet submarines patrolled the Caribbean with permission to fire nuclear-armed torpedoes at our Navy without first consulting the Kremlin. Faced with inbound tankers and military calls for an all-out assault, Kennedy, a World War Two naval officer himself, called on the Navy to impose a blockade around the Caribbean, which he conveniently called a "quarantine" because, after all, a blockade is an internationally recognized act of war. But if you call it a quarantine, it's all good.

Khrushchev called the quarantine an illegal blockade and ordered the Soviet transport ships to keep on steaming.

There were several close calls during the Cuban Missile Crisis. One of the closest was with the Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine B-59. As part of the Cuban quarantine, US destroyers began dropping signaling depth charges on B-59. The signaling depth charges sounded suspiciously like, well, real depth charges to the crew hundreds of feet below the surface with little radio contact with the outside world. Moscow had been silent for days. B-59's captain wondered if Moscow still existed. Perhaps it was a smoking pile of radioactive slag after the perfidious American nuclear strike. B-59's captain decided to launch a nuclear torpedo.