The Battle of Memphis and it’s prelude the Battle of Plum Point was a pivotal moment in the struggle for control of the Mississippi River during the Civil War. This slice of campaign culminated on June 6, 1862 and was the first, and last major fleet-on-fleet action in the Mississippi. I’ll spoil the surprise and tell you that it was over almost as quickly as it began with a decisive Union victory that allowed Union forces to continue grinding their way down the Mississippi.

But the battle's swift conclusion and one-sided outcome have led many to dismiss its significance. This is a mistake. Had the Confederate River Defense Fleet prevailed—or even survived as a "fleet in being"—future Union operations in the Mississippi Valley would have been severely hindered.

The battle pitted three fleets against each other: two Union fleets and one Confederate, ironically all under Army control.

After taking control of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers that we talked about earlier in this mini series, forcing the Confederates to abandon the citadel of Columbus without a fight, and then smashing Island Number 10 into submission, Memphis was the clear next objective for the Union; it was the largest city between New Orleans and St. Louis and it was a vital transportation hub where railroads converged. The Confederacy, however, made a critical error. They choose not to allocate scarce resources to adequately fortify Memphis, believing the upriver fortifications would be sufficient protection.

In June 1862, two unusual Union fleets converged on Memphis. One was led by Commodore Charles Davis, a professional naval officer with no experience in river warfare. The other was commanded by Colonel Charles Ellet, a former bridge engineer with neither nautical nor military experience.

Facing them was the Confederate River Defense Fleet under Commodore Joseph Montgomery, a former Mississippi river pilot thrust into a military role. This clash of improvised naval forces would decide the fate of the Upper Mississippi.

In the spring of 1862, as Union forces pushed down the Mississippi, the Confederate desperation was showing. They did not have the resources to build a war fleet from scratch, and so they improvised by building a ragtag fleet of converted civilian steamboats commanded by riverboat captains with no naval experience. This was the River Defense Fleet, brainchild of Captains Joseph Montgomery and James Townsend.

The necessity of using these converted river steamers appalled the few professional naval officers in the Confederate Navy. As one sneered, it was an "anomalous, inefficient, useless and expensive expedition." Yet, New Orleans was the biggest city in the Confederacy and defending it was the priority for the best ships of the Confederate Navy, and so the Upper Mississippi was left with no better options.

The fleet was improvised. Fourteen steamers were hastily seized in New Orleans and converted into rams. Their bows were reinforced with massive timbers and iron plating. Engines were protected by double bulkheads packed with compressed cotton. Each boat received a single stern-mounted cannon - though as one of the professional naval officers noted, "I do not believe one of the officers in command of any of the vessels of the fleet knew how to load or manage heavy guns."

Since the south lacked the ability to produce enough iron to properly armor the improvised fleet. Instead of a thick iron plating over the whole ship, armor was just an inch thick and covered only the most vital areas. Bit there was not even enough for that. When the iron available fell short, Captain Townsend simply ordered his men to tear up three miles of railroad track.. Of course, this had an impact on the transportation of war goods, so it really is the definition of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The eight boats that headed upriver to defend Memphis were a motley assortment given that each was build off the base of a different, non-standard river steamer.. The CSS General Bragg could make 10 knots while the lumbering uparmored paddlewheeler General Jeff Thompson could barely make her way upriver weighted down by cannon and armor. Their crews were steamboat men, used to carrying cargo, not waging war.

Nonetheless, this motley civilian armada now stood as the Confederacy's last naval defense on the upper Mississippi. As General Braxton Bragg wrote to one of the boat captains, "Hope ere long you will be able to test with success the efficiency of your boats, which are now the last hope of closing the river to the enemy's gunboats."

The Union fleet was another story. By late spring of 1862, the Union's Western Flotilla was an eclectic, evolving, but purpose-built war fleet.

The backbone of the fleet was the seven City Class ironclads: Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis (later renamed Baron De Kalb). Designed by naval architect Samuel Pook and constructed with remarkable speed by engineer James Eads, these vessels were designed in a matter of weeks, and for the fast work, did decently for a v1 gunboat.

Each City Class ironclad measured 175 feet long and 51 feet 2 inches wide, with a shallow draft of just 6 feet when fully loaded. Their casemate design, armored with 2.5-inch iron plating, made them formidable, but left significant vulnerabilities. The vessels were only partially armored, with unprotected areas exceeding the protected ones.

Their armament was impressive but evolved over time. Initially, each carried thirteen guns: six 32-pounder smoothbores, three 8-inch smoothbores, three 42-pounder Army rifles, and one 12-pounder boat howitzer. However, by August 1862, the armament had diversified, with some boats carrying 50-pounder Dahlgrens and 30-pounder Parrott rifles.

Their lack of power was a constant issue. With a top speed of just 4 knots upstream, they were painfully slow. This deficiency was exacerbated by their poor maneuverability, a result of the trade-off between firepower and mobility in their design.

Complementing the City Class gunboats was the unique USS Benton, a converted snagboat that became the most heavily armed vessel on the river. At 202 feet long and 72 feet wide, it carried an impressive 16 guns. However, it was even slower than its City Class counterparts, often requiring tows to make headway against the current.

The flotilla also included more unorthodox craft. Thirty-eight mortar boats, or "scows," were built under Army contract in St. Louis. Each carried a single 13-inch mortar capable of hurling a 200-pound shell over three miles. However, these vessels were little more than rafts and presented numerous operational challenges. Captain Henry E. Maynadier, Commander of the Mortars, reported:

"It is almost impossible to tow them without running them under water, whilst their construction is, as I shall endeavor to show, very badly adapted to resisting the effects of firing."

Despite these issues, the mortar boats proved their worth in bombarding Confederate fortifications from beyond the range of return fire. During the siege of Island No. 10, Foote admitted: "The mortar boats do well, and had we a place to put them out of the sight of the forts we could soon shell out the rebels. They have done good execution as it is."

Perhaps the most controversial addition to the flotilla was the Ram Fleet, created by civilian engineer Charles Ellet Jr. Right now in naval history we are in this weird moment where armor can plausibly defend against offensive firepower, and so there was a degree of thought that another solution was needed. Enter, the ram, which had not been used since the days of rowing galleys. Under direct authority from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Ellet converted seven civilian steamers into rams. These vessels were reinforced with heavy timbers and iron plating at the bow, designed to sink enemy ships by ramming them rather than gunfire.

Ellet's rams were fast, with an estimated speed of at least 18 kts downstream. They carried no heavy guns initially, relying instead on their ramming power and small arms for defense.

Crewing these vessels was an equally eclectic mix. Regular naval officers commanded the ironclads, but given the manyfold increase in the size of the navy over the course of the prior year, many of these naval officers were recent civilians with limited naval experience. Pilots, crucial for navigating the treacherous Mississippi, were highly paid civilian contractors, often earning more than the vessel commanders. Many crewmen were soldiers detailed from the army, while others were riverboat men or newly freed slaves.

As the Union fleet moved down from Island Number 10 to the next fortification in the Mississippi, Fort Pillow just north of Memphis, the two fleets met, with a sense of foreboding that settled over the Confederate side who knew their own shortcomings. Commander Pinkney of the Confederate Navy's regular squadron, in a display of what we might charitably call excessive caution, refused to join Montgomery's attack plans. "It would be murder to make such an attempt," he declared, his words spreading through Montgomery's fleet like a virus, infecting the men with doubt.

On the Union side, Foote found himself plagued by a recurring nightmare - the specter of Confederate vessels slipping past his flotilla to wreak havoc in the currently uncontested upriver. "The exposed state of the river above," he wrote to Welles, "induces me to act with the greatest caution, as momentous consequences are involved in the issue." Even one marauding Confederate quasi-ironclad would stall the logistics superhighway and require him to divert a huge portion of his own squadron to go and hunt the river raider down., which in an age of slow communication could take quite a long time among the countless tributaries and hidden inlets of the Mississippi.

The tension ratcheted higher as May dawned. Montgomery's captains debated attack plans nightly. Should they, as the commanding officer of the CSS General M. Jeff Thompson suggested, attempt a daring night raid through the Union line to attack their transports? The experienced river men among Montgomery's captains balked at the idea. It was never a good idea to try and navigate the sand bars and tricky currents of the Mississippi at night, and they could easily envision their vessels running aground or colliding in the darkness.

Meanwhile, the Union fleet remained on high alert, steam up and guns loaded. Foote had emphasized readiness, issuing orders that commanders must ensure their boats were "ready for battle at a moment's warning."

In this atmosphere, even routine events took on an air of menace. When a Confederate boat approached under a flag of truce to return paroled Union surgeons, many in the Union flotilla suspected an ulterior motive. Were the Confederates merely using this as a pretext to scout their positions?

Amid the circling of the fleets just above Fort Pillow, Foote was finally forced to relinquish command due to a lingering foot injury from the Battle of Fort Donelson. As he handed over control to Captain Charles H. Davis on May 9, that very evening the Confederate commanders gathered to discuss their attack plans. Finally, they settled on a plan - they would attack in column formation at dawn, with their fastest boats leading the charge.

As night fell on May 9, both fleets lay at anchor, their crews restless with anticipation. The mighty Mississippi flowed on, indifferent to the human drama playing out on its waters, carrying with it the fate of a nation divided.

In the murky dawn of May 10, 1862, the Confederate fleet, led by the Commodore Montgomery launched their daring (or desperate, it’s a fine line) plan.

And here I’m going to do a little bit of quoting and a bit of summary of the Battle of Plum Point from To Retain Command of the Mississippi by Edward B. McCaul Jr.:

“Sometime between 6:25 and 6:30 a.m….men on board both the Cincinnati and the mortar boat saw the masts and smoke from the stacks of the leading Confederate rams before they came around Craighead Point. …. Confederate surprise was complete, as the crew of the Cincinnati was involved in doing routine tasks. … It was a hurried beat to quarters. Besides the crew doing routine work, steam was not adequate to fully maneuver the boat, and the engineers were forced to throw "oil and everything else inflammable into her fires that the necessary head of steam might be obtained to handle the boat." For their part, as soon as they rounded Craighead Point and saw the enemy, the Confederate captains ordered their engineers to open every valve on their engines so they could get maximum speed from their boat.

At about this same time, some of the men on the ironclads moored to the north bank saw the smoke from the stacks of the Confederate boats. Based on that information, the drums beat the men to quarters. Commodore Davis on the Benton ordered that the signal be passed to all boats to get under way. There was some delay, as the boats—according to naval discipline—could not go into battle before the commanders received a signal from the flotilla commander, Commodore Davis, nor could they be in front of the flagship when going into battle. Still, the Carondelet, commanded by Commander Henry Walke, having its steam up, quickly slipped its hawser and headed down river. As the Carondelet passed the Benton, Commodore Davis ordered Walke not to wait but to go immediately to the aid of the Cincinnati. However, not all of the boats were as quick as the Carondelet as, in disobedience of standing orders, neither the Benton, Pittsburg, and St. Louis, nor the Cairo had its steam up…. Fortunately, someone on the Mound City spotted the Confederate rams, and the Mound City got under way about the same time as the Carondelet, even before its captain… saw the signal from Davis. … It was a bad start for the Union.

…The Cincinnati cast off, even before it had enough steam to maneuver, and drifted with the current to meet the onrushing Confederates. Once the Confederate rams were within range, the Cincinnati fired its bow guns—to no effect. The Bragg, the leading Confederate boat, under the command of Captain William H. Leonard, steamed up the main channel on the Arkansas side of the river past the Cincinnati. Once there, Leonard turned his boat back toward the Cincinnati, maneuvering to avoid the Cincinnati's cannon fire. With General Thompson on board, the Bragg, going at full speed and assisted by the river current, struck the Union gunboat immediately after the Cincinnati had turned toward it to avoid being rammed in its vulnerable stern. Due to this maneuver, the Bragg hit the Cincinnati on its starboard quarter…just behind the shell room, crushing in that side of the boat, filling the shell room with water, and knocking down all of the crew and anything loose. The impact was so powerful that it spun the Cincinnati 180 degrees, with the Bragg following along…While the boats circled each other, the crew of the Cincinnati went back to their posts and fired a broadside into the Bragg at point-blank range. The projectiles went through the Bragg …[only doing] superficial damage…

Immediately after being struck by the Bragg, the General Price and Sumter rammed the Cincinnati. The General Price… received two broadsides from the Cincinnati's two stern guns as it approached, but the damage was minimal, and the General Price struck the Cincinnati on the starboard side just behind where the Bragg had rammed it. …One of the Cincinnati's rudders and part of its stern torn off. The Cincinnati was rapidly sinking; as the Sumter approached, its commander…offered to save the crew if they would haul down their flag. The response was: "Our flag will go down when we do!" The Sumter then rammed the Cincinnati's port side of the fantail …with the Cincinnati rapidly sinking, Acting Lieutenant William R. Hoel, who had assumed command as Stemble was partially paralyzed [after being hit by a sniper], ordered that the Cincinnati be run aground on one of the sandbars on the Tennessee side of the river…fortunately for the Cincinnati, the water was too shallow for the Confederate rams so the Cincinnati was not rammed again; another ramming would likely have completed its destruction…

Although the other ironclads were not able to immediately help the Cincinnati, [some of the mortar boats were]... by adjusting the mortar so that the projectiles were being fired almost vertically. …While the mortar shells did little damage to the Confederate boats [because of the inherent inaccuracy of shooting vertically and hoping that a giant cannonball would land on a moving target], they had a psychological impact. Montgomery stated in his after action report that the mortar boat "was filling the air with its terrible missiles." Although destroying the [expendable] mortar boat[s] was not one of the Confederate fleet's objectives, its firing drew attention to it, and at least the Price and Van Dorn fired at it. …

After ten to fifteen minutes, the USS Mound City and Carondelet got close enough to assist the Cincinnati and distract Confederate attention away from her…the CSS Van Dorn, after firing at the mortar boat, charged toward the leading ironclad, the Mound City. The Mound City fired continuous broadsides at the Van Dorn, but they did little damage, and at the last minute, the Mound City sheared away in an attempt to avoid being rammed by the Van Dorn. The result of this maneuver was that the Van Dorn rammed the Mound City about four feet from the bow on the starboard side…the Mound City was turned around while the Van Dorn continued straight ahead and ran aground on the Tennessee side of the river. The damage done to the Mound City was extensive, as its bow was almost completely wrenched off. The Van Dorn was in trouble, too: While the crew of the Van Dorn was trying to free the boat, the Mound City, Carondelet, Benton, Pittsburg, and St. Louis were directing cannon fire at it…

Commodore Montgomery, whose boat the Little Rebel had been in the thick of the action, observed that the Union ironclads were staying in water too shallow for his rams, and that the majority of the Union fleet was beginning to get into close range. Consequently, he signaled his fleet to fall back, even though his three heaviest and largest boats were just arriving. The Union boats and the mortar raft continued firing at the retreating Confederates as long as they were in range but, again, these shots did little or no damage…

The Battle of Plum Point redoubled the Union's naval commanders' fear of a Confederate boat that was faster than their ironclads getting past them and going upriver. Roger Stembel, the wounded commander of the Cincinnati, emphasized his dread in a letter to James Eads. Stembel wrote that, in his opinion, the object of the Confederates "was if successful in disabling our fleet, which I am sure they hoped to do, to proceed up the river, capture, burn, and destroy all that might fall in there [sic] way, and you [Eads] can readily conceive from your knowledge of the localities, etc., what a destructive raid they might have accomplished." Fear of such an event clearly had an impact on all Union naval operations, because boats were left behind to guard tributaries, thus weakening the Union fleet. Even though it was not as easy to disrupt as wagon- or railroad-borne supplies, river transportation still could be thwarted, with far more serious impact. Foote and Davis had a similar opinion, as Stembel as Davis wrote to Gideon Welles that "Flag-Officer Foote thought it might be the intention of the enemy to pass the flotilla and ascend the river, and if they should attempt to do so, such is their vast superiority in speed, that pursuit would be hopeless."

Plum Point was a hard-fought victory for the Confederacy, in which it did not lose any boats; but it was a battle with no positive long-term results, as it did not slow down the Union advance or help delay the fall of Fort Pillow. However, the damage the Confederate rams inflicted on the Union fleet impressed the Union fleet's commander and officers. David D. Porter commander of the Mississippi Squadron, stated after the war, "Our iron-clads showed themselves unsuited in respect to steam power, to cope with swift river vessels that could ram them and then escape." One result of the battle was that the ironclads were modified for better protection against rams.

The Cincinnati and Mound City were quickly repaired and returned to duty. The Mound City rejoined the flotilla by May 22, with the Cincinnati ready for action during the first week of June. The Confederate rams were repaired even more quickly, even though the "funnels looked like huge Nut-Meg graters, and the upper works were completely riddled, on the Boats [sic] that had closed with the enemy." The battle proved that wooden rams could defeat heavily armed ironclads and escape with minimal damage, thus bolstering confidence among the Confederates.

Union commanders made a number of errors before and during the battle. First, they allowed themselves to be surprised, even though they had been warned that the Confederates planned to attack. Plus, no battle plans or general orders had been issued or discussed on what each boat was to do in case of an attack. Then, the damage inflicted by the rams was a shock, especially as it was discovered that cannon fire did not stop them.… Intelligence reports on the type of Confederate boats they were to fight were also incorrect. Union commanders thought that while some of the Confederate boats were rams, other boats were grappling boats, designed to capture their boats. Harry Browne, who was on the deck of the Mound City during the battle, wrote home that many of the Sailors on board the Mound City were afraid the Confederates would grapple the Cincinnati and drag it downriver. Another problem was the potential for fratricide. Walke stated in his after action report that, at times, they were "more in dread of her [Pittsburg] shot than those of the enemy," although no one was injured by these misdirected projectiles. This problem was a direct result of the poor visibility and the haphazard deployment of the Union fleet. … An almost fatal mistake on the part of the Union commanders was disobedience of General Orders No. 4, in that their boats were not ready for battle at a moment's notice. This negligence caused the Union fleet to engage the Confederates piecemeal, not have all of its ironclads involved in the battle, and allowed multiple Confederate rams to attack individual ironclads.

The victory the Confederate River Defense Fleet achieved at Plum Point raised false expectations that the fleet could not fulfill. On May 12, the Memphis Avalanche newspaper reported, "The impregnability of our cotton clad fleet is now considered to be fully demonstrated – the enemy's shot penetrating into the cotton only a few inches and not passing through. Therefore there is now no danger of the enemy reaching Memphis via Fort Pillow." Two days later, the Memphis Avalanche reported, "The conviction seems to be in that quarter [Fort Pillow], that we can hold the Mississippi river with the fort, assisted by our fleet of cotton-clad boats." However, the Confederate fleet, even with its tremendous effort at Plum Point, and the garrison of Fort Pillow, was not able to prevent the fall of Fort Pillow due to circumstances beyond its control. The campaign for control of the Mississippi River valley was a joint naval and land effort for both sides, and command of the river depended on each effort being successful.

Ellet, an engineer with more ambition than naval experience, arrived at Plum Point bristling with ideas and impatience. He wrote to Secretary of War Stanton, "To me, the risk is greater to lie here with my small guard and within an hour's march of a strong encampment of the enemy, than to run by the batteries and make the attack." But Commodore Davis, a more cautious commander, was reluctant to risk his ironclads in a frontal assault on the fort.

This clash of personalities and strategies created a rift in the Union command. Ellet complained to Stanton that Davis "will not join me in a movement against them, nor contribute a gunboat to my expedition, nor allow any of his men to volunteer so as to stimulate the pride and emulation of my own." The two commanders were at loggerheads.

But while Ellet and Davis bickered, events on land were reaching a climax. Union forces under Colonel Graham Fitch, using intelligence provided by Confederate deserters and escaped slaves, found a approach to Fort Pillow that would allow the Union infantry to avoid detection by the Confederates and get within thirty yards of the fort’s outer works. By June 4th, they were poised to strike. The stage was set for a dramatic assault - but fate had other plans.

In the early hours of June 5th, Colonel Fitch made a startling discovery. Fort Pillow was empty.

“The Union capture of Corinth. [Corinth was the small city just on the Mississippi side of the Tennessee-Mississippi border where the Confederate army had retreated after the defeat at Shiloh. Just 80 miles to the east of Memphis, Corinth’s fall] on May 30, and the cutting of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, made the Confederate positions on the Mississippi north of Memphis untenable, including Forts Pillow, Randolph, Wright, Harris, as well as Memphis itself. The problem the Confederacy faced was that it did not have sufficient troops to garrison the forts and oppose the advance of [the Union] army. Besides, the heavy guns necessary to defeating the Union ironclads were in short supply. As a result of the loss of Corinth and the planned evacuation of Fort Pillow.”

The Confederates had slipped away in the night. Fitch sent an urgent message to General John Pope: "Arrangements were completed for a combined assault on the fort at 7 a.m. at a weak and accessible point, but the works were abandoned last night, and the guns and commissary stores destroyed. We are in possession, but propose proceeding to-day toward Memphis." The defense of Memphis, the fifth largest city in the Confederacy at the start of the war, now rested solely on the strength of the Confederate River Defense Fleet.

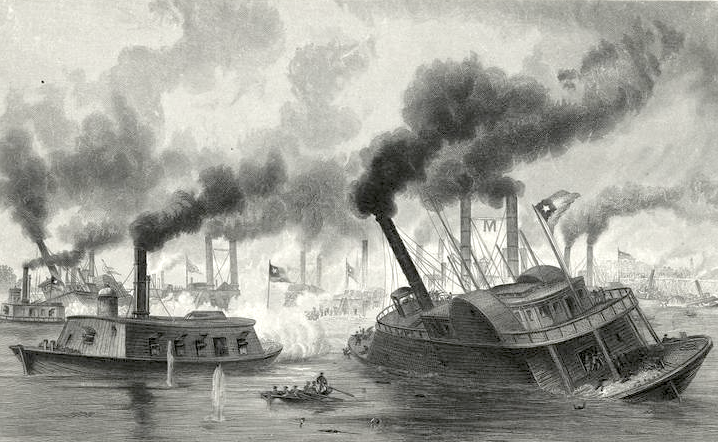

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1862, the citizens of Memphis gathered on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. Estimates ranging from 15,000 to 40,000 spectators, to witness what would become one of the most dramatic naval engagements of the Civil War.

The stage was set: Commodore Charles H. Davis's Union ironclad fleet faced off against the Confederate River Defense Fleet under Captain James E. Montgomery. As the sun rose, casting a glare across the water, the Confederate Jeff Thompson opened fire, igniting a fierce artillery duel.

Initially, it seemed the Confederates held the upper hand. Their gunners, perched higher on their vessels, scored hits on the Union ironclads. But this advantage came at a cost. As one New York Tribune reporter observed, "The enemy fired very wildly, either from excitement or discouragement, and had in some instances... shot at a distance of less than 30 yards without hitting their object."

The tide of battle turned dramatically with the sudden appearance of Colonel Charles Ellet Jr.'s ram fleet. The USS Queen of the West, followed closely by the Monarch, charged through the Union line, catching both sides by surprise. As the Queen of the West bore down on the Confederate ram Lovell, she at the last moment veered, presenting its broadside.This was a catastrophic mistake, presenting a prime target to the massive Union ram.. An eyewitness described the scene: "The hull was crushed in, and its smoke stacks threatened to fall into the river." The Lovell sank rapidly, taking 75 of her 80-man crew with her.

The two hours were a chaotic melee of ramming, cannon fire, and desperate maneuvering. Visibility plummeted as smoke from the guns and boats' stacks obscured the battlefield. In this confusion, friendly fire became a real danger. The Confederate rams Beauregard and Price, both aiming for the Monarch, collided with each other instead.

The battle's gruesome nature was evident in the fate of the CSS Jeff Thompson. Union shells set its cotton bale armor ablaze. Unable to control the inferno, its captain ran the boat aground. Hours later, the flames reached the magazine, and the Thompson exploded in a spectacular fireball.

By 0730, just two hours after the first shot, the battle was over. The Union had achieved a decisive victory, destroying almost the entire Confederate River Defense Fleet. In the aftermath, Captain Davis wrote to his wife, "Thank God for this great success. If the gunboats had fled before me, as their speed easily enabled them to do, they would still have been a thorn in our side. Now they can give us no further trouble."

The Battle of Memphis stands as a testament to the rapidly evolving nature of naval warfare in the Civil War. Ironclads, rams, and traditional gunboats clashed in a spectacle that would help shape the future of naval combat. More immediately, it secured Union control of the Mississippi River, a critical strategic objective in the Western Theater of the war.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Memphis, the Union quickly moved to secure the city. Colonel Ellet, in a brash display of initiative, sent his son Charles into Memphis with a small party to raise the American flag. As young Ellet and his companions made their way to the post office, they were met with some understandable hostility, given that they were the alone and unafraid first representatives of a conquering power in the city. An angry mob surrounded them, hurling rocks and firing pistols.

The situation grew tense. As Ellet's son raised the flag atop the post office, Confederate sympathizers attempted to storm the roof. A quick-thinking policeman saved the Union men by standing on the trapdoor, preventing the mob from reaching them.

Colonel Ellet, upon hearing of his son's predicament, issued a stark ultimatum to the mayor: ensure the safe return of the men and keep the flag flying, or face bombardment. This threat was issued without consulting Commodore Davis, and Ellet lacked the firepower to carry it out. Yet it had the desired effect.

Davis, taking a more measured approach, formally requested the city's surrender. Mayor John Park's response was telling: "The civil authorities have no resources of defense, and by force of circumstances the city is in your power." With those words, Memphis fell into Union hands.

The battle itself had been a bloody affair for the Confederates. At least 100 men perished, with 75 going down with the Lovell alone. More were scalded to death when the Beauregard's boiler exploded. The River Defense Fleet, that ragtag collection of converted steamers, had met its inglorious end.

The battle's outcome was decisive. It gave the Union unchallenged control of the upper Mississippi, save for the occasional guerrilla attack which meant that, it secured a vital supply line that the Confederates could not seriously interrupt. As Davis wrote to his wife, "Thank God for this great success. If the gunboats had fled before me, as their speed easily enabled them to do, they would still have been a thorn in our side. Now they can give us no further trouble."

Member discussion: