It's a great quote the the beginning, right?

So long as the sun shall warm the earth, let no Christian dare come to Japan. And, let all know that if the king of Spain himself or his Christian's God, if he violates this command, shall pay with his head.

-Shogun's edict of 1638

We find ourselves in naval history more than 200 years after the Shogun issued an edict that cut Japan off from the West, and for the past 200 years, Japan had been a closed and mysterious land. Japan's sole link to the Western world was a small Dutch settlement on Dejima Island, off the coast of Nagasaki, where 25 Dutch traders were allowed to maintain a small facility. One Dutch trade ship arrived and departed each year from Nagasaki to conduct trade. But ever since American commerce had been freed at the end of the War of 1812, and picking up even more after America gained a Pacific coastline after the Mexican-American War, American traders began looking towards Japan as a land of opportunity and trade. The commerce-minded President Fillmore in 1851 began seriously exploring options to open Japan to American shipping and sent Perry to open Japan, which had proved to be one of the, if not the single most significant event in Japanese history.

Less than a century after Perry initiated the opening of Japan, Japan transformed itself into a great power and would contest the United States Navy for control of the Pacific in World War Two. As I alluded to, Japan was a closed society. In 1603, the Tokugawa clan won a civil war and established the Tokugawa shogunate just a few years later. The Tokugawa shogunate isolated Japan from the Western world for many reasons, but one of them was that outside forces were seen as destabilizing and the current power structure was fine with them on top (thank you very much!). The Emperor was relegated to a powerless religious Pope-like figure, a prisoner in his own palace and unknown to the average Japanese. 260 Daimyo each ruled a province called a Han, and samurai culture, urbanization, economic growth, and strict class structures evolved.

But by the 1800s, the Shogunate was weakening, and many Daimyos were getting restless. Split between those who wanted openness and reform and those who backed the Shogun and his close regime. But as ignorant as the West would remain about the closed islands of Japan, Japan was not as ignorant about the rest of the world. The Japanese shogunate allowed a small Dutch settlement to exist on the island of Dejima, off the coast of Nagasaki. And one Dutch trade ship was allowed every year to trade with Japan. Throughout Japan, there were schools of Dutch learning where Western knowledge was studied, which led some to become increasingly convinced that Japan needed to turn towards the west to not fall behind.

Increasingly by the 1800s, the outside world was closing in on Japan. To the north, the expanding Russian empire, which had added Siberia more than a century ago, was slowly probing the northern islands by the early 1800s. During the Napoleonic Wars, where the Dutch were driven by the British bombardment of Copenhagen into becoming allies (or really puppets) of the French, some American ships traded with Japan under Dutch flags with permission of the Dutch government. Also during the Napoleonic Wars, a British warship followed a Dutch ship into Nagasaki Harbor and seized a Dutch trade ship, which the Japanese could not stop. In 1842, the end of the first Opium War for the neighboring Chinese empire was crushed by a relatively small but more technologically advanced British force shocked the Japanese leadership, who had thought of the Chinese as the most powerful and advanced country in the world. This increased the calls for openness and reform.

In 1846 and 1849, United States Navy made other attempts to try and contact Japan, but each failed when the Japanese refused to deal with them, leading to the recommendation that only a show of force would cause the Japanese to pay attention. In 1851, Fillmore authorized the mission, and Perry was eventually selected for command. Perry was chosen for a couple of reasons. For one, he was seen as one of the more forward-thinking senior officers in the Navy. He was an advocate of steam power, a combat veteran in the Mexican-American War, and considered diplomatic and studied everything he could about Japan, not that much was available, before leaving on his mission. He sailed his fleet from Norfolk around the world until he reached the Ryukyu Islands, which are south of mainland Japan, and spent some time putting on a show of military force, but also hospitality to local leaders to demonstrate his peaceful intent.

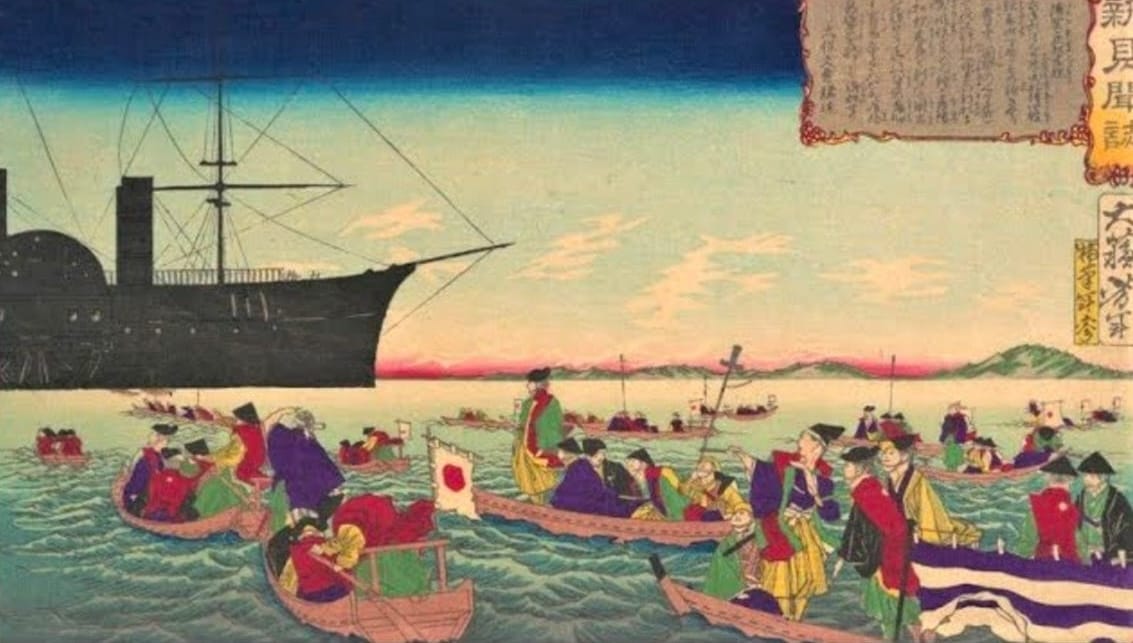

Perry then sailed four of his ships, including two steamships, into Edo Harbor (today Tokyo), which was the capital of the Shogunate. Although it probably wasn't apparent to Perry from his place in the harbor at the time, Eto was one of, if not the largest city in the world. After it was opened, Westerners described it as beautiful, advanced with canals and hundreds of palaces because each of the 260 Deimos had at least one and maybe up to three, because they were required to spend every other year in Edo, essentially as hostages of the Shogun, as a way of maintaining Shogunate power.

For the Japanese, this was almost like aliens landing on Earth today. The average Japanese had never seen or heard of Westerners. The ships were absolutely huge compared to Japanese ones. They had paddle wheels, were painted black, and they were moving and belching coal smoke on a windless day. The Japanese told the Americans to leave, but they did not. Through an emissary, Perry demanded that a high-ranking official come and take a letter from President Fillmore to the Emperor of Japan. This just goes to show how limited the Western world's knowledge of Japan was since the emperor at this point was a powerless guy who was a prisoner in his own palace. Why would the Americans want to talk to this dude? Doesn't he want to talk to the Shogun?