This one is going to be a mini post where I cover the interwar period. If you’re not familiar with the term, the “Interwar Period” is the roughly twenty-one-year period between the end of WWI in 1918 and the start of WWII proper in 1939. During this period, we obviously had the roaring (19)20s followed by the Great Depression. This was, and I don’t think I am spoiling anything here, followed Pearl Harbor and WWII which kicked the country into economic overdrive. The interwar years get glossed over pretty often, but during this period naval development was very interesting and set the stage for WWII to turn out the way it did. So, I am going to very briefly discuss four things in this post:

- The Washington and London Naval Treaties which laid out the sizes and types of navies each major naval power could wield.

- The technological shifts the treaties accelerated, specifically the development of aircraft carriers and naval aviation.

- The war planning the United States was doing during this period.

- A little bit about what the Marine Corps was doing during this period and how that would prove to be significant during WWII.

WWI "Winners" and Losers

After WWI ended in November of 1918, the victorious world powers looked around realized that even the winners were losers. Yea, Britain and France gained a bunch of colonies and protectorates from the defeated Central Powers, and yeah they were theoretically going to get a reparations payday down the road, but HOLY SHIT, if you’ll excuse the language, it was not freaking worth it. France alone suffered over a million killed in action[^1] with another more than four million wounded. Europe’s economy was destroyed, governments had taken on mind-boggling amounts of debt to fight the war, and the fundamental problem of Great Power competition which led to the war had not been fundamentally altered.

President Wilson’s idea to prevent a repeat was called the League of Nations, a sort of pre-United Nations-like body which ultimately failed to do much. The one power that came out well from the war, if you can call it that, was the United States because we came in late and basically just gave the Allies a push over the edge at comparatively minimal cost.

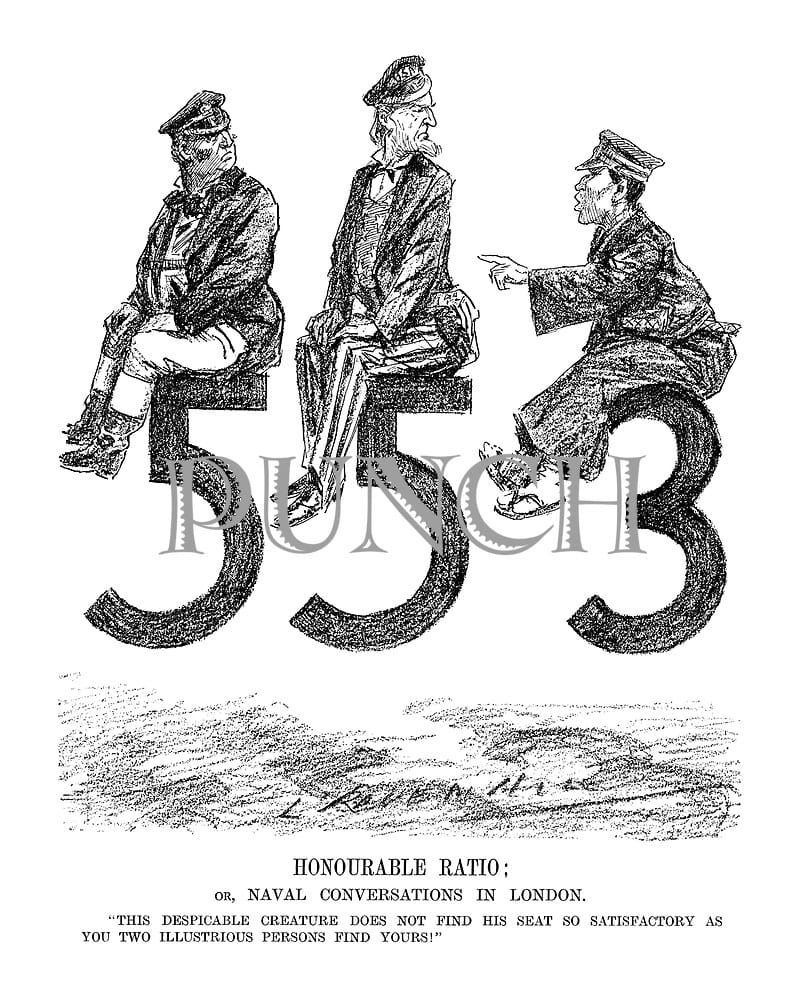

The Washington Naval Treaty

Looking around at the wreckage of the Europe, President Warren Harding, Wilson’s successor, saw that only a few countries in the world had any ability to project power overseas. After the Germans scuttled their fleet rather than turn it over to the British after WWI, the only countries with significant fleets had been on the same victorious side of WWI. Harding figured that if he could limit the ability of these nominal allies to fight far from their shores, it would not only make the United States completely secure but also reduce the inclination of countries to go to war in the first place. And so, under the threat of the United States finishing Wilson’s Second to None navy plan which would leave everyone else’s navy in the dust, the Washington Naval Treaty was signed in 1922 by the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy. This treaty regulated the number and total tonnage of dreadnoughts. allowing Britain and the United States to hold an equal number, allowing Japan fewer at a 5:3 ratio, and Italy and France a lower 5:1.67 ratio of capital ships.

These hard caps and ratios mandated that the United States, Britain, and Japan each had to scrap existing battleships and theoretically prevented an expensive naval arms race between friends that nobody wanted to engage in. This started what was called the “Treaty System” or the “Treaty Navy” period. There would be another naval conference in London in 1930 which extended the arms control limits to other classes of ships as well. With treaties in place, Congress and post-war administrations basically left the Navy to its own devices to figure out how it should build and plan for the future.

Interwar Naval Technology

As a result of new technology, the limits placed on battleships after the Washington Naval Treaty, and the pretty lenient limits on aircraft carriers, naval aviation came into its own during the interwar period. Immediately after WWI most naval officers still considered planes as scouts and spotters for the fleet, but that gradually began to change. As naval aviators struggled to convince the service that they should have an expanded role, an Army-Air Corp General Billy Mitchell was making even bolder claims. Base on his WWI experience, he theorized that America could, and should, stop relying on battleships for continental defense and instead develop a system of bombing and pursuit aircraft to more cheaply and effectively defend the homeland.

General Billy Mitchell, Naval Theorist

Billy Mitchell was a visionary, but the sort of visionary who got really pissed off at anyone who didn’t share his vision. He spent the early 1920s making a lot of enemies. He called most of the navy obsolete and his criticism of military leadership ranged from “shortsighted” and “slow-moving,” to “treasonable.” To make his point, Mitchell got the by-now furious Navy to agree to a series of tests on his claims that he could use planes to sink ships under wartime conditions. Using surrendered German ships as targets, various bombing experiments were conducted, although unlike during wartime the ships were stationary and not firing back. Mitchell’s planes succeeded in sinking the German targets and for anyone who was willing to use a little imagination, common sense, and forward thinking, the message was undeniably clear that planes could sink even the biggest ships.

Billy Mitchell's test bombings.