This week we are going to tackle a big topic, the Civil War. In this titanic conflict, the Navy began with only 42 ships in active service and orders to blockade 3,500 miles of coastline and seize control of the South’s rivers. Over the next four years the Union navy would swell to almost 700 warships, lead the world technologically, and play a vital part in reuniting the nation in the bloodiest war the United States has ever fought. The war can also be thought of as the first modern war, a total war where technology, industry, and joint operations played decisive roles and marked a clear transition from the Napoleonic era of horse and infantry line tactic warfare, into the era of screaming shells, trenches, and the scorched earth of the 20th century.

Beginning with the election of the anti-slavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln who was so unpopular in the South that he did not even appear on the ballot in ten southern states, southern states began to secede, led by South Carolina where 58% of the population were black slaves. Lincoln intended to keep his inaugural oath to “preserve, protect, and defend” the Constitution and nation. When Lincoln authorized a supply ship to reinforce the loyal troops at Fort Sumter in the middle of Charleston harbor, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the surrounding forts to open fire on Sumter which surrendered two days later. The next day, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to join the army, triggering four more states to secede and beginning the Civil War.

The Navy’s biggest strategic proponent early in the war was the US Army’s General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, known by his men as “Old Fuss ‘n Feathers.” Scott proposed to Lincoln that the navy adopt a complete blockade of the Confederate coastline and take the Mississippi River, while the Army would grind away at the Confederates in Northern Virginia. This strategy became unofficially known as the “Anaconda Plan” and would exploit the weaknesses of the South. With little industry and railroad track, the South would be reliant on cash raised through the sale of slave-produced cash crops to buy supplies from overseas and coastal vessels for internal transportation. Taking rivers would also open up new fronts in the war which the less populous Confederacy did not have the manpower to defend. Throughout the war, Scott’s proposed Anaconda would slowly crush the Confederacy through an attritional war which, unfortunately for the Confederacy, could not be fought with cotton bales.

Establishing and Maintaining the Blockade

Five days after the surrender of Fort Sumter, Lincoln announced a naval blockade of the Confederate States, which at least initially existed only on paper. With hundreds of small ports, rivers, and inlets scattered along 3,500 miles of coastline, Lincoln was proposing the greatest blockade in world history, and one that even the greatest navy in the world would have found an impossible task. And the United States Navy was far from one of the greatest in the world. With only 42 ships in active service and most of those scattered around the world on squadron duty, the twelve ships that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells estimated that could be put to sea “at once” was not going to cut it. Wells recalled the squadrons at once and placed orders for 24 steam and propeller driven warships he didn’t have the funds to cover on the (correct) assumption that Congress would agree to fund them retroactively. He simultaneously began the mass conversion of merchant steamships into make-do warships for blockade duty.

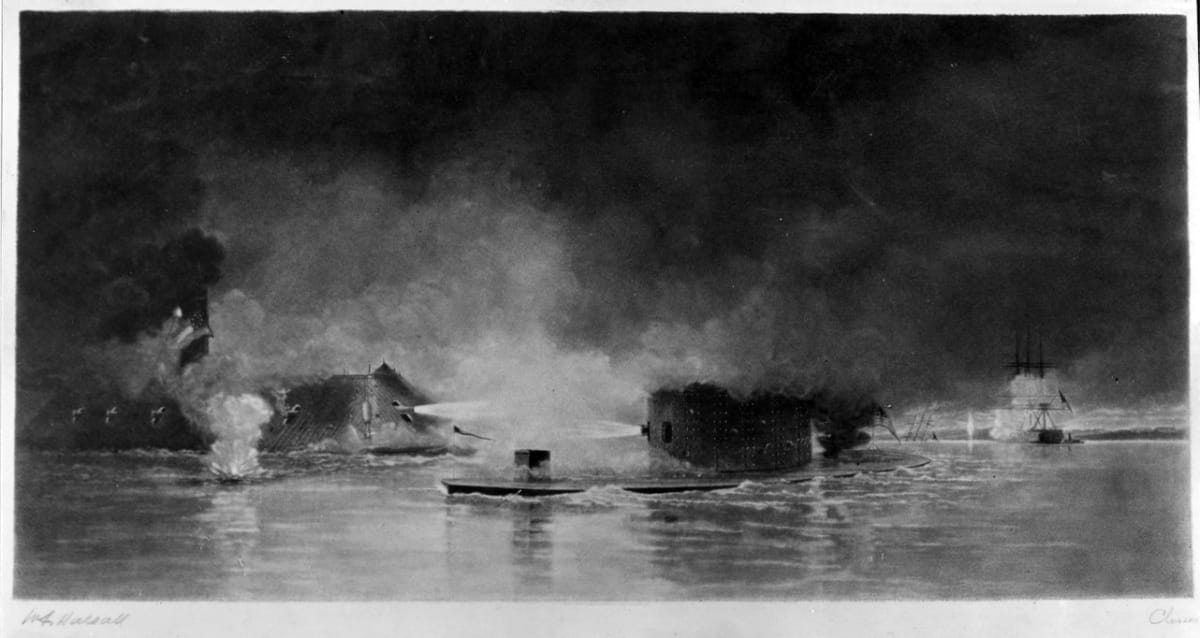

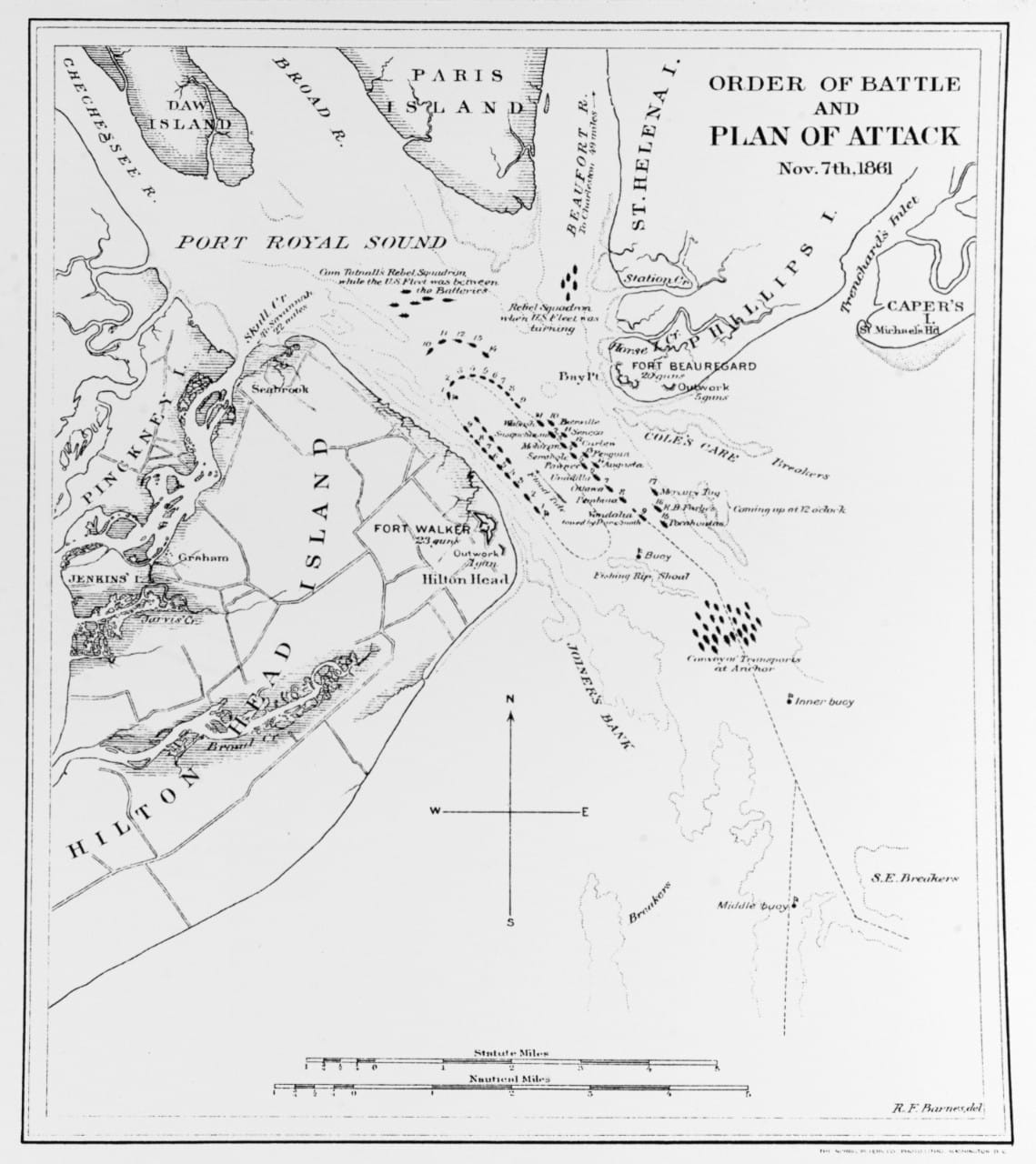

The advantages of steam warships were clear and few sailing ships were built through the war, but the Union faced the logistical problem of supplying all these new ships with coal. The Navy decided to accomplish its blockade it would have to capture and hold bases off the Confederate coastline to serve as staging and logistical bases for the fleet. The first of these bases was Port Royal, halfway between the major Confederate ports of Savanah to the south and Charleston to the north and protected by swamps from counterattack by land. With a squadron of eight warships including the USS Pocahontas whose captain’s brother commanded one of the defending forts, Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont led the squadron and 70 Army transports full of supplies and men into battle. With naval cannons outranging the guns of the two Confederate forts defending Port Royal, Du Pont sailed his warships in racetrack ovals firing on each port on one leg of the oval until both forts were forced to evacuate and taken by the Army. Similar operations would go on to establish bases at Biloxi, Mississippi, Key West, Florida, and Hampton Roads, Virginia to serve as major bases of operation for the blockading fleet.

Blockade duty itself was……terrible. They consisted of hot, boring days at sea keeping an eye on the horizon outside of minor ports and inlets hoping to see the smudge of soot indicating a ship, but on most days, most weeks, and even most months there was nothing. The Confederacy had only traces of a navy and all of the big, slow transport ships usually used to carry cotton to European factories were abandoned or used for scrap. Maintenance and cleaning filled the days, just like most days for most sailors aboard warships today. When night fell, especially on moonless nights and during foul weather, full watch kept an eye out for shadows gliding across the water or the soft chuff of steam which indicated a small, fast blockade runner might be trying their luck, heading for Spanish Cuba or British Bermuda where they would offload their cargo of cotton to a neutral ship and take on a load of goods for the return race home. When a lookout thought that they might have seen something, signals and flares were shot into the sky and bells rung bringing the crew up from their hammocks and to battle stations ready for a chase, firing at the fleeing blockade runner whenever they were in range. About 80% of the time the blockade runner dispiritingly got away, but those 20%’s add up over the years especially when the blockade had to be run in both directions, and by the end of the war over 1,400 blockade runners would be captured or destroyed.

A few factors helped the Union with the blockade, especially early in the war when the Navy’s blockade of the massive coastline was more theoretical than anything. The first was a move that in hindsight was unbelievably stupid on Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s part: to institute a self-embargo based on the mistaken theory that British and French textile producers were so dependent on Southern cotton that by withholding this vital input they could convince one or both European powers to intervene on the Confederacy’s behalf. Davis prevented the export of hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of cotton to raise money for the purchase of war material. The British largely shrugged off the export ban and were able to increase cotton production across their empire instead. The second big mistake the south made regarding the blockade was its failure to regulate what the blockade runners were importing until late in the war. With limited capacity, every blockade runner should have been importing guns, gunpowder and other industrial war goods the rebelling southern states could not produce for themselves, instead of what they thought would bring them the most profit, which often included consumer goods due to the widespread shortages, leading to sky-high prices in the south throughout the war. Jefferson Davis’s embargo was reversed after 1861 and the blockade runners were eventually regulated, but by then the Union blockade was much tighter, the Confederacy missed their golden window, and seriously harmed their war effort.

By the last year of the war, Confederate cotton exports had been cut by over 95%, but equally if, not more important, was the blockade’s effects on the internal transportation of the Confederacy. With all coastal maritime traffic cut off, more demand was placed on the already inefficient and underdeveloped southern railroad system. As the railroad system began to break down throughout the war and the south lacked the industrial capacity to make up for the losses, both the civilian population and the military began to suffer. Bread riots erupted in major cities and the supplies the Confederacy did have were often stuck hundreds of miles away waiting for transportation to the front. Overall, the blockade probably helped speed along victory and over the course of the war the Army and Navy worked together in what were then called Combined Operations to gradually capture most of the major ports and coastal cities in the Confederacy, but alone that would not have been enough to force the Confederacy to accept Union dominance.

Confederate Guerre-de-Course

The Confederacy’s response to the blockade, along with blockade runners, was the typical response of a weaker naval power when fighting a stronger one: commerce raiding, just as the United States had used so effectively against the British during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. From the first days of the war, the Confederacy issued letters of marque to entrepreneurs, but the scheme overwhelmingly failed, with 21 Confederate privateers capturing only 18 Union ships, compared to the approximately 500 American privateers who captured over 1,400 British ships during the War of 1812. The reason for the Confederate privateering failure was the refusal of neutral ports to accept the captured vessels and the blockade of Confederate ports which stripped the profit from the endeavor. In place of privateers the south used commissioned raiding ships. Although the Confederacy could only afford a dozen of these British-built raiders, they managed to burn 228 Union merchant ships. The most famous and successful of these raiding captains was Raphael Semmes. When the war started Semmes resigned his commission in the United States Navy, commissioned in the Confederate States Navy, and was given command of the converted paddle wheeler CSS Sumpter. Sailing her through the Caribbean and across the Atlantic, Semmes captured or burned 18 Union merchantmen before being trapped in Gibraltar by US Navy warships. Selling the ship, Raphael Semmes and his officers made their way to Liverpool and Semmes took command of the CSS Alabama and an international crew of seamen. Over the next year, the Alabama led Union pursuers from the North Atlantic, through the Caribbean, to the Brazilian coast, into the South China Sea and back again, capturing or burning 64 ships along the way before being sunk off the coast of France by the USS Kearsarge.

The River War and Combined Operations

Still, the coastal blockade was only half of the navy’s contribution to the war effort: the other half consisted of the river war. General Scott’s original Anaconda Plan called for the Union to seize the Mississippi River. You can’t really overstate how important control of major rivers was in this era, especially when fighting on such a huge and still relatively underpopulated area like the southern United States. The side which controlled the rivers could move their armies and supplies faster and outflank the enemy. Control of the Mississippi in particular would split the Confederacy, allow the Midwest to export its huge food surplus, provide Union troops a huge front from which to strike out against the Confederate interior, and of course, deny all of the river’s advantages to the south. For this task of riverine warfare, the War Department funded the construction of steam-powered, shallow draft gunboats, many with iron plate armor, to combat the series of fortifications the Confederacy had erected to defend their waterways. Command of these gunboats was given eventually to United States Navy Captain Andrew Hull Foote who worked closely with General Ulysses S. Grant to provide artillery support and transportation to the army. Working together, Grant and Foote first cracked open Fort Henry which guarded the Tennessee River and allowed Foote’s gunboats to raid as far as the river draft would allow in Alabama, destroying Confederate warships, transport vessels, and military supplies along the way. Grant and Foote attempted the same tactic against Fort Donelson which guarded the Cumberland River, which turned out to be a disaster for the gunboat fleet. From their batteries forty feet above the river, the much stronger Confederate fort ripped apart Foote’s gunboats. But while Foote’s gunboats dueled Fort Donelson’s guns, Grant’s soldiers surrounded the fort and forced it’s surrender, along with all 12,000+ defenders, and opened up the defenseless interior of Tennessee which the Union quickly captured including one of the South’s few, vital industrial cities of Nashville.